Welcome to the fourth edition of First Nations News & Views. This weekly series is one element in the “Invisible Indians” project put together by Meteor Blades and me, with assistance from the Native American Netroots Group. Last week’s edition is here. In this edition you will find an update on the Cheyenne River Reservation Okiciyap project , this week in American Indian history, five news briefs and some bullet links. Click on any of the headlines below to take you directly to that section of News & Views or to any of our earlier editions.

125th Anniversary of the Infamous Dawes Act

North Dakotans Still Fighting Over ‘Fighting Sioux’ Nickname ~ Interior Dept. Set to Clean Up Dawes Act Mess ~ GOP Exploits Navajo Division Over EPA Toxic Rule ~ Nation’s First Tribally Owned Wind Farm Planned for Maine ~ American Indian Elders Incorporated into Learning Curriculum at Schools

It has been 182 years since the Indian Removal Act was signed into law by President Andrew Jackson. With tribes then and for decades afterward being forced onto reservations, and no Marshall Plan to help them rebuild after the Indian Wars, Native people are still struggling to stay alive. Many don’t make it. Fighting against all odds-of poverty, 80 percent unemployment, hunger, government bureaucracy, societal indifference-a few people stand as warriors to help their communities of limited means even when they themselves often don’t have enough means, living as they do on fixed incomes of $260 to $460 a month.

One of those warriors is Georgia Little Shield (Lakota). She was the director of Pretty Bird Woman House, a women’s shelter on the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation, from 2005 until 2010 when health problems forced her to quit. In 2007, the Daily Kos community helped raise more than $30,000 to keep Pretty Bird Woman House running.

In 2011, Little Shield’s health improved. On the Cheyenne River Reservation in north-central South Dakota due south of Standing Rock, she saw an important need for a community-strengthening program to fight poverty, hunger and the epidemic of teen suicide.

So she founded Okiciyap, the Lakota word for we help, in Isabel, a reservation town of about 250 people. Okiciyap (we help) the Isabel Community‘s (501c3) first project is a food pantry “trying to keep families alive for one more winter.” The group has plans to build a youth center with a GED program “to keep our young people’s souls and spirits alive, too.”

Last summer, Okiciyap set up a temporary office in a small trailer. Later, a modular 40-foot by 60-foot building was donated. But it was located 30 miles from Isabel. Ten thousand dollars were needed to transport it, set foundation forms and skirt them. Another $10,000 is needed to set up utilities for one year until Okiciyap can obtain grants to keep the facility running on its own. Under the auspices of AndyT and betson08, netroots fundraising began in late October to pull together the needed $20,000. By the end of December enough money had been raised to transport the building to Isabel. The trek was completed Jan. 30.

Within Lakota culture everything is shared. There is great pride and pleasure in giving away any abundance of food, clothing and other possessions. There is traditionally no social hierarchy of haves and the have-nots. So even though Little Shield doesn’t always have much to share, she shares it anyway.

After Thanksgiving last November, betson08 discovered that Little Shield didn’t have enough money to buy a turkey for her own family, but she still cooked what she had and invited people who needed food. The week before Christmas betson08 learned the same thing was going to happen. The Daily Kos community rallied again and raised enough for Little Shield to provide a holiday banquet for the community plus provide toys for the kids.

The Okiciyap fund-raising widget has now been stuck at $10,580 for a month. That $9420 still needed will allow Okiciyap to tie into the city’s water and sewer system plus cover the cost of electricity and provide basic office equipment and supplies.

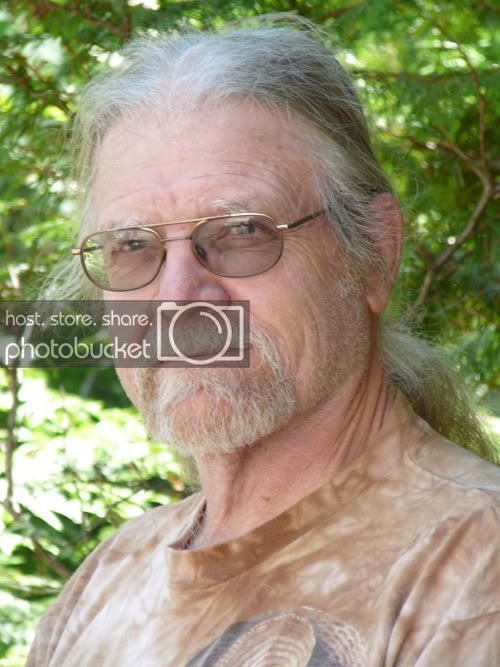

Little Shield’s appearance below is one of satisfaction in watching the new building arrive. She’s embarking on an ambitious new project that she hopes will help her community tremendously. The Daily Kos community has a stake in helping her succeed.

– navajo

(Library of Congress)

February 8th marked the 125th anniversary of President Grover Cleveland’s signing of the Dawes Act. That single piece of legislation had a more devastating impact on Native Americans than anything other than the century-long Indian Wars themselves. And it was initiated by people who actually believed they had Indians’ best interests at heart. Before it and follow-up acts were effectively repealed 47 years later by the Indian Reorganization Act, 90 million acres had been wrenched from communally owned Indian land, leaving just a third of what the tribes had held in 1886, the year Geronimo, the last organized warrior, surrendered and was shipped off to prison. What land wasn’t directly taken was “allotted” to individuals. Taking and dividing the land coincided with a stepped-up effort to destroy Native culture, religion and governance, in effect, “Indianness.”

Named after Sen. Henry L. Dawes, who headed the U.S. Senate Committee on Indian Affairs, the law was the culmination of practices toward Indians that had begun within a decade of the Pilgrim landing at Plymouth. Boiled down to their essence, those policies said to Indians: Get out of our way, or else. Even getting out of the way often wasn’t enough to prevent the “or else.” The Dawes Act itself arose at least partly out of the influence of a book written by Helen Hunt Jackson in 1881, A Century of Dishonor. It was the Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee of the 19th Century, documenting the bloodthirsty avarice and corruption that had suffused Indian-U.S. relations all those decades since the first war in 1788. Jackson didn’t live to see the Dawes Act passed, but she would no doubt have approved.

(This Week in American Indian History continued below)

The intent was assimilation, “killing the Indian to save the man,” turning Indians into farmers of acreage they held individually, altering gender roles, shattering kinship connections, breaking up communal land and tribal government, and, ultimately, wiping out reservations altogether. Officials thought this would be better for everyone as Indians adopted norms of the dominant culture. It would certainly be good for transferring some prime real estate.

What the new law did was allot 160 acres to each head of household and 80 acres to each single adult over 18. This land would be held in federal trust for 25 years, after which ownership and citizenship would go to Indians still working their allotment. To take full possession of any land a woman had to be officially married. All inherited land passed through the male head of household. This broke the tradition of tribes with matrilineal heritages.

“Surplus” land, that is, what was left after allotments, was flung open to white settlement and ownership. That was the provision’s most likeable quality for congressmen and businessmen who would just have soon have slaughtered or starved every Indian still alive. Half the Great Sioux Reservation was sold to outsiders after Indian allotments were distributed.

As Youngstown University Asst. Prof. G. Mehera Gerardo has noted, even before the ink was dry on the act, speculators were making deals to trade or buy Indian lands. But they mostly postponed development for fear the government would confiscate what they’d shadily acquired before the trust period expired. Thus were many Indians able to keep to their traditional ways of life for another decade, treating the land as if it were still held communally, even though they’d already bargained their allotments away. State and local governments soon found ways around the law to permit outsiders to buy allotments. Hemmed in by fences, cut off by private ownership of forests and riverine areas, Indians now found themselves no longer able to subsist on hunting and fishing.

Meanwhile, funds from the sale of reservation land, which were supposed to benefit the tribes, were mismanaged, often not paid for decades, sometimes outright embezzled. Money that did make it to the proper federal accounts was often used for things Indians did not find worthwhile. The late historian Melissa L. Meyer wrote, “Facile generalizations about Anishinaabe dependence on welfare gratuities mask the fact that they essentially financed their own ‘assimilation.’”

Thanks to the lobbying of those for whom no amount of freed-up Indian land was enough, new federal legislation was passed in 1906 to allow Indians to sell their allotments well before the end of the trust period. Many, hating farming or broke from trying, sold at rock-bottom prices. Those who had actually received land suitable for farming, and much of it was not, couldn’t afford the tools, seed, animals and other supplies required. Small government grants were insufficient and most could obtain no credit. They had received no training. Even if parents knew how to farm, children coerced into boarding schools came home years later without the necessary skills. Inherited land was often divided among too many heirs to be large enough to farm.

The dispossession was wildly successful. Partly as a consequence of the act, by 1900 the American Indian population had fallen to its lowest point in U.S. history, about 237,000.

– Meteor Blades

North Dakotans Still Fighting Over ‘Fighting Sioux’ Name

Petitioners for a statewide referendum to keep the University of North Dakota’s “Fighting Sioux” nickname have exceeded by several thousand the 13,452 signatures they needed to get the issue on the June 12 ballot, according to Secretary of State Al Jaeger. He now has a month to ensure that the signatures are valid.

The fight over the nickname and an accompanying logo of an Indian in feathers has been going on for decades. In 2006, the NCAA instituted a policy requiring schools to abandon nicknames, logos and mascots considered “hostile and abusive” to American Indians. Any school that chose to ignore the policy would be sanctioned by not being allowed to host championship games nor wear its team logo at postseason games. Exceptions were made for schools that got consent from relevant tribes to keep using their nicknames. Tribal permission was obtained for the University of Utah Utes, Central Michigan University Chippewas and Florida State University Seminoles. FSU even got to keep its Appaloosa-riding “Chief Osceola” mascot.

UND took a different approach. It sued. But it lost. In the settlement it agreed that if it could not gain consent from the two Sioux tribes in North Dakota by the end of November 2010, it would begin retiring the nickname and logo. But the university could only get one of the two tribes to agree. A vote by the 6700-member Spirit Lake Tribe (Sisseton Wahpeton), which has long been active in support of keeping the name, approved UND’s request by a 2-1 margin. Tribal member Frank Black Cloud told Time magazine in December: “Why should the NCAA come in and tell us that we should be offended?”

However, the tribal council of the 8900-member Standing Rock Tribe (Lakota, Yanktonai, Dakota) rejected the name. It refused to hold a tribal vote, however, and would not accept petitions seeking a vote of the whole tribe. Councils of other Sioux and non-Sioux tribes, like North Dakota’s Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians, have passed resolutions against keeping the name.

The North Dakota legislature responded by passing a law in April 2011 requiring UND to keep the “Fighting Sioux” name and threatening an anti-trust lawsuit against the NCAA if it imposed sanctions. With the law in hand at a meeting last August in Indianapolis, top UND officials, North Dakota legislators and the governor met with the NCAA to get it to change its decision. In a completely unsurprising move, Spirit Lake was not asked to participate. “How can we not have a seat at the table?” Black Cloud complained.

After the NCCA refused to budge, the legislature backed off, repealing the pro-nickname law in November. UND immediately began removing the logo and name from its web sites, ordering new uniforms with a simple “ND” in a circle on them and making other changes that officials estimate will cost $750,000. Under the law, no new name can be chosen until the end of a 36-month “cooling-off period.”

Faced with the imminent switchover, citizen petitioners, including a few Indians from both Spirit Lake and Standing Rock, began gathering signatures. Because of the way referendums work in North Dakota, the repeal of the pro-nickname law is now held in abeyance until the balloting takes place. To comply with the law, the UND president has reinstated the “Fighting Sioux” name. Meanwhile, another group of is circulating a separate petition that advocates a pro-nickname amendment to the North Dakota Constitution. They need 26,904 signatures to get the issue on the ballot for November.

Even if one or both referendums pass, however, there is another sticking point. More and more schools are saying they will refuse to compete with UND if it continues the “Fighting Sioux” nickname. Here is a comprehensive timeline of the Fighting Sioux controversy.

-Meteor Blades

Interior Dept. Set to Clean Up Dawes Act Mess

The Interior Department announced Feb. 2 that it plans to spend $1.9 million to buy fractionated American Indian lands and restore them to the tribes. The program stems from the historic $3.4 billion settlement in Cobell v. Salazar, a class-action lawsuit filed over a century’s worth of gross mismanagement of royalties for Indian trust lands. The suit was brought by the late Elouise Cobell (Niitsítapi [Blackfoot]), also known as Yellow Bird Woman.

The proposal is open for public comment until March 15. Nothing will move forward on it until four appeals of the Cobell settlement are dealt with. A key issue in those suits is that the settlement failed to uncover even a close approximation of how much money got “lost” from the federal land trust accounts.

The fractionation emerged out the tribe-smashing Dawes Act of 1887 that allotted lands to individual Indians and opened the “surplus” to non-Indians. Over several generations, the heirs of these allotments found themselves owning smaller and smaller plots unsuitable for farming or any other commercial uses and unsalable because of the logistics of getting all owners to agree. Original allotments ranged from 80 to 320 acres, depending on the status of the individual Indian and the location of the land. Some allotments now have as many as 1000 owners, many of whom are unaware they even own their small piece. The Associated Press says the Interior Department has identified 88,638 fractionated land tracts owned by nearly 2.8 million people.

Over 10 years, the program will work first on tracts with the most owners, targeting land that will take the least preparatory effort to gain a controlling interest. No individuals will be forced to sell their allotments. Once a buy is completed, the land will be returned to communal ownership by the tribe, the very thing the Dawes Act tried to destroy.

John Dossett, the general counsel for the Native Congress of American Indians, said the draft proposal appears to address most of the tribes’ major concerns. Of particular importance was that the tribes be involved in implementing and administering the land consolidation program through cooperative agreements, which are addressed in the draft plan.

“It’s a problem that has been sitting around for a hundred years or more,” he said. “I think tribes are really interested in doing this right. You don’t get a do-over on $1.9 billion.”

Cobell died in October a few months after the settlement was approved by a federal judge.

-Meteor Blades

GOP Exploits Navajo Division Over EPA Toxic Rule

House Republicans were at it again last week, seeking to justify their opposition to the imposition of stricter guidelines for mercury emissions by the Environmental Protection Agency. At a hearing of the Subcommittee on Energy and Power, they used a ploy that has a long history in Indian-U.S. relations, finding an Indian who will go along with whatever it is particular politicians want while excluding Indians who don’t.

In this case, the Indian on the GOP witness list was Navajo Attorney General Harrison Tsosie. Like Navajo Nation President Ben Shelley, Tsosie opposes the EPA’s four-year time-line for complying with the Mercury and Air Toxics Standards (MATS), which imposes national limits on lead, arsenic, mercury and acid gases emitted from power plants that burn coal and oil. Tsosie said power plants in and around the Navajo Nation would need 20 to 25 years to upgrade. Those plants include Navajo, Cholla, Four Corners, San Juan and Escalante. He said the toxic rule would also force the shut down of coal mines on the Navajo Nation.

“Indian nations are often cited as being pockets of poverty … and the one common denominator is pervasive federal control,” Tsosie [testified]. “The United States EPA MACT rule is no exception and adds yet another regulatory burden tribes are left to contend with.” […] “Revenue and job losses of that magnitude would be cataclysmic for the Navajo Nation and its people, and would certainly impugn the very solvency of the Navajo Nation government,” his written testimony said.

Tsosie’s wife, Gerilyn (Navajo), works in an administrative job with BHP Billiton, the Australia-based mineral and energy giant with worldwide coal operations, including in the United States. Tsosie’s view is not shared by all Navajos, especially those who live near the generating stations. Waheah Johns of the Black Mesa Water Coalition is one of those. She was born atop Black Mesa, land sacred to the Navajo and Hopi. The mesa, which rises suddenly from the dry, red plains around it, was the centerpiece of a bitter three-decade battle over strip-mining and water use, which pitted the Bureau of Indians Affairs and Peabody Coal against the tribes and the tribes against each other. Not only does Johns support the EPA standards, she “doesn’t buy the job loss argument”:

“[W]e’re very happy the EPA stood their ground on behalf of our children. Just think how many Navajos are going to be employed installing the new equipment,” she said. “This rule is going to create jobs, not destroy them. […] It opens the door wide for alternative energy.”

The EPA toxic release inventory says the five big power plants around the Navajo Nation collectively have released 14.6 million pounds of mercury, chromium, lead, nickel and hydrochloric acid into the air in the past 10 years.

-Meteor Blades with a h/t to Aji and John Walke

Nation’s First Tribally Owned Wind Farm Planned for Maine

(Photo by Joyce Scott)

Joining a growing number of tribes installing renewable energy operations on their land, the Passamaquoddys of Maine hope to have between 18 and 50 wind turbines generating electricity for up to 21,000 homes by 2013. To get there requires passing through a few bureaucratic hoops, including the purchase of surplus government land. The remote location of the proposed wind farm is now home to blueberry barrens and cranberry bogs and an abandoned Air Force radar site. Because all the land involved is held for the tribe in federal trust, only federal permits will be required to install the wind turbines.

The $120 million wind farm is a joint project of the tribe and the Boise, Idaho-based Exergy Development Group. It will be called Peskotmuhkati Wind LLC (after the Indians’ own word for Passamaquoddy). Clayton Cleaves (Passamaquoddy), chief of the Pleasant Point reservation. said his tribe own 51 percent of the project and will invest profits in other local projects. additional projects. “This can be a key economic driver for the Passamaquoddy Tribe,” he said.

Tribal ownership of the wind farm is unique. That arrangement took place on the advice of John Richardson, a consultant the tribe hired for the project. Richardson, formerly Commissioner of the Maine Department of Economic and Community Development and at one time Speaker of the House of Representatives in the Maine legislature, is a principal in Native Power LLC. The firm’s goal is to ensure majority ownership by tribes of project relying on wind, solar and other renewable resources. Peskotmuhkati Wind is its first effort. No U.S. tribe currently has such ownership of any large-scale energy projects on tribal lands.

Richardson said that seeing the project succeed was very important to him because of the struggling economy in Washington County. “What is most significant is that because the wind project will be owned by the tribe, the majority of revenues created by the wind farm and other businesses will remain in Washington County,” he said. “This could be a game changer for the county.” […]

“We became interested in this project because it is a first-of-its-kind development of a commercial-scale wind power project that is uniquely owned with Native Americans,” James Carkulis, president and CEO of Exergy said Tuesday. “We have also been highly encouraged by the Department of Energy and the Bureau of Indian Affairs analyses that we are a national model of how to navigate development and financing of renewable energy projects on tribal lands.”

-Meteor Blades

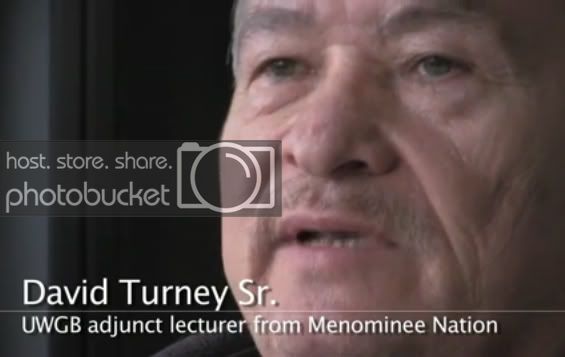

American Indian Elders Incorporated into Learning Curriculum at Schools

As a result of the modern battle over over fishing and treaty rights in the 1980s, Act 31 was passed into Wisconsin law in 1991 to require K-12 schools to learn about federally recognized American Indian tribes and bands in the state. University of Wisconsin-Green Bay established The First Nations Center in 2009 to help teachers better understand this requirement. In recent years UW-Green Bay has enhanced this program by including one-on-one training with tribal elders to further help future educators have a more accurate knowledge of American Indian culture and in particular, a better understanding of nearby tribes.

This good news comes on the heels of last week’s report of a 7th grader being punished instead of praised for speaking her Native language in class at Sacred Heart Catholic School, also in Wisconsin. This boarding school-like incident is the very situation Act 31 was designed to try to prevent. UW-Green Bay also recognizes that weak stabs, such as making paper head-dresses for elementary programs or dance performances for older students, is not a true fulfillment of the legal requirement for which there are no enforcement provisions.

Elder David Turney Sr. (Menominee), who also goes by the name Napos, teaches Menominee Ethnohistory and Introduction to First Nations Studies as an adjunct lecturer at UW-Green Bay. For example, he uses his tribal religion to teach the seven principles of the Menominee Nation. Turney teaches the one-word Menominee guidelines translated into English phrases meaning to have love and goodness, search for knowledge, have strength to help others, build wisdom to teach one day as an elder, respect everything, and to be humble and be truthful. He says, each these should be a factor in how you make your decisions to control the way you live on this earth.

UW-Green Bay’s program is a work in progress to address continuing stereotypes and help students to gain an appreciation of the various tribal cultures.

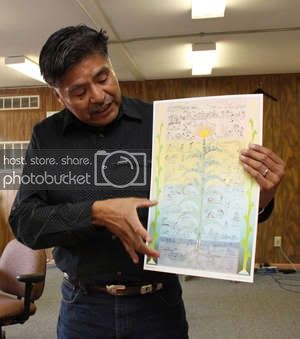

At Northwest High School in Shiprock, N.M., Wilson De Vore (Navajo) is the first traditional counselor in the district to use Navajo culture to help students. De Vore helps his Native students with their identity issues and feels he can relate to them because he also was a problem student. He uses the Hero Twins, deities in Navajo religion, to tie students to their culture, not for conversion but to reinforce their pride.

The twins, as legend has it, visited Spider Woman to learn the identity of their father. After learning he was the Sun, the boys traveled to him, seeking weapons that would allow them to defend their people against the monsters and create harmony.

One of the twins, Monsterslayer, confronts the negativity in life […] and his brother follows to generate resolution.

Students are encouraged to use the story to find resolution to modern struggles.

“I feel students have monsters today, life struggles that cause imbalance,” he said. “I tell the students that in each of them lies the Hero Twins. You have a choice. You can go about using aggression or you can go about creating balance and harmony.”

De Vore plans to build a sweat lodge on campus and bring appropriate Navajo ceremony experiences to the students and faculty. He says traditional teachings can be incorporated into every academic subject.

(Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara)

Dr. Alyce Spotted Bear (Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara), a former tribal chairwoman of the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation in North Dakota and recently appointed by President Obama to serve on the National Advisory Committee on Indian Education, is now part of the Native American Center’s Elder-in-Residence program at Fort Lewis College in Colorado.

The Elder-in-Residence program brings prominent individuals from the American Indian community to meet with staff and students in an effort to increase knowledge and understanding of First Nations Cultures at the college.

Speaks Lightning

(Anishinaabe)

Here at Daily Kos we have another example of utilizing traditional experts in education. Dr. E. B. Eiselein (Anishinaabe), who writes here and at Native American Netroots as Ojibwa, has been teaching Native American Studies at Flathead Valley Community College for the past 30 years. He says, one of the challenges in teaching in a college environment is that it is not appropriate to teach some things, particularly regarding ceremonial traditions, in this context. As a traditional ceremonial leader he does invite students to participate in open ceremonies. His course description on Native American Spirituality is here.

– navajo

• Oglala Restores Wounded Knee Mass Grave Site: Volunteering his time, masonry materials and his all-Native employee labor to renovate the 121-year-old cemetery, Julian Brown Eyes (Oglala Sioux Tribe) honors the men, women and children who were murdered by the 7th Cavalry in December 1890.

– navajo

• UPDATE: S.D. House Panel Rejects Flag with Medicine Wheel Motif: The traditional state flag touting the Mount Rushmore monument will not change to a design honoring indigenous tribes. But if tradition had been honored in the first place the sacred Black Hills would not have been carved with the faces of its conquerors. (See brief in Feb. 5 News & Views.)

– navajo

• Navajo Nation Wins One Uranium Waste Cleanup Fight : Tribal experts proved the Highway 160 waste-dumping site should have been part of the federal cleanup program that ended in 1997. The cleanup is now completed. The tribe has other waste sites it wants the government to remediate.

– navajo

• California Tribes Strive to Keep Pomo Language Alive: Only a handful of fluent speakers of Southern Pomo are still live and they’re over 90. But, using a full array of modern technology, linguistics teacher Alex Walker is trying to revive the Northern California Indian language by teaching some 20 Pomos the idiom that their parents and grandparents were punished for speaking.

– Meteor Blades with a h/t to maggiejean

• Ski Resort Wins Case to Make Wastewater Snow on Peaks Sacred to Tribes: The Save the Peaks Coalition and individual members of the Navajo Nation have been fighting a legal battle to prevent a ski resort from further desecrating the San Francisco Peaks near Flagstaff since 2005. The latest ruling allows Snowbowl to use 100% reclaimed sewer water to make snow, something not done anywhere else in the world.

– navajo

• Oglala Sioux Sues Anheuser-Busch, MillerCoors, and Liquor Stores in White Clay: The tribe blames the huge beer makers for knowingly exploiting alcohol sales to liquor stores in White Clay, Neb., which has a dozen residents but sold nearly 5 million cans of beer in 2010. Nearby Pine Ridge reservation has struggled with alcohol abuse as a result of pervasive poverty since the 1800s.

– navajo

Indians have often been referred to as the “Vanishing Americans.” But we are still here, entangled each in his or her unique way with modern America, blended into the dominant culture or not, full-blood or not, on the reservation or not, and living lives much like the lives of other Americans, but with differences related to our history on this continent, our diverse cultures and religions, and our special legal status. To most other Americans, we are invisible, or only perceived in the most stereotyped fashion.First Nations News & Views is designed to provide a window into our world, each Sunday reporting on a small number of stories, both the good and the not-so-good, and providing a reminder of where we came from, what we are doing now and what matters to us. We wish to make it clear that neither Meteor Blades nor I make any claim whatsoever to speak for anyone other than ourselves, as individuals, not for the Navajo people or the Seminole people, the tribes in which we are enrolled as members, nor, of course, the people of any other tribes.

Leave a Reply