Welcome to the eighth edition of First Nations News & Views. This weekly series is one element in the “Invisible Indians” project put together by Meteor Blades and me, with assistance from the Native American Netroots Group. Last week’s edition is here. In this edition you will find a focus on Native and AIDS/HIV, a look at the year 1824 in American Indian history, five news briefs and some linkable bulleted briefs. Click on any of the headlines below to take you directly to that section of News & Views or to any of our earlier editions.

This Week in American Indian History in 1824

Oglalas Face Criminal Charges for Civil Disobedience Related to Canadian Tar Sands ~ Dakota Descendants Seek Memorial for Largest U.S. Mass Execution ~ Ancient Alutiiq Kayak to Revive Construction Knowledge ~ Youngest Iditarod Winner Ever ~ Drunken Indian Poster Celebrates Record Company’s Anniversary

By Aji

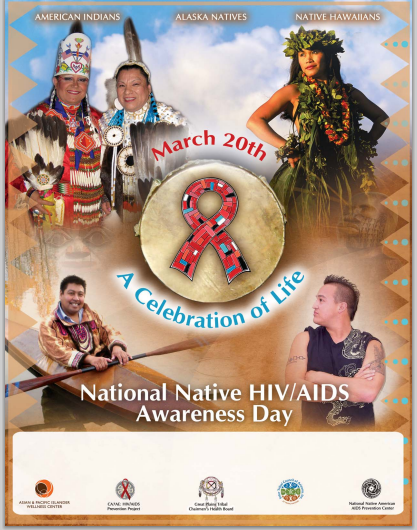

When you think of the face of HIV/AIDS, it probably doesn’t look like this – but maybe it should. Meet Kyle. He’s a young American Indian man. And he’s HIV-positive.

When you think of the face of HIV/AIDS, it probably doesn’t look like this – but maybe it should. Meet Kyle. He’s a young American Indian man. And he’s HIV-positive.

Tuesday, March 20, is National Native HIV and AIDS Awareness Day.

American Indians now constitute the third-fastest-growing ethnic group with new diagnoses of HIV and AIDS: 10.4 for every 100,000 persons. At first glance, that number seems much smaller than the rate for Hispanics, at 27.8/100,000, and that for African Americans, at 71.3/100,000.

However, the numbers are deceptive. First, as with everything else related to American Indian health, rates of HIV and AIDS are without doubt substantially underreported. Second, “current” estimates are already seven years out of date: The most recent global figures compiled by the Centers for Disease Control are from 2005, and the trends indicate greater rates of infection since then. Indian youth are becoming infected with HIV at faster rates than whites, with shorter survival times.

Third, talking about rates of HIV/AIDS in American Indian communities in terms of numbers per 100,000 population misses the forest for the trees. In the 2010 census, a mere 5.2 million people identified themselves as American Indians, either wholly or in part. That’s only 1.7% of the total U.S. population of some 308 million people. At that level, a diagnosis rate of 1/100th of a percent is a great deal more significant for the entire ethnic group.

And, according to CDC research covering diagnoses between 1997 and 2004, of all ethnic groups, American Indians and African Americans have the shortest rates of post-diagnosis survival: 67% and 66%, respectively, at the end of the period’s nine-year follow-up.

For a demographic in which 26% of those infected don’t even know they have HIV, awareness has now become a matter of both individual and ethnic survival.

It can be disheartening to read the literature of the world of HIV/AIDS awareness and outreach. Even efforts geared toward people of color regularly omit American Indians. Those that do remember to include them too often do so from a dominant-culture perspective that doesn’t even realize that there are cultural and other differences that must be recognized and incorporated into any successful outreach program. This approach makes Indian health, wellness and survival a mere afterthought. And all the red ribbons in the world won’t do a thing to increase awareness of the growing threat that HIV and AIDS present to our communities, much less enhance prevention and ensure survival.

The good news is that several Indian nations have already taken steps to create HIV/AIDS awareness, education, diagnosis, and treatment programs that are culturally relevant and respectful of tradition. Partnering with the Indian Health Service and other public health entities, these efforts target this most underrepresented and underserved of populations in concrete ways.

The Navajo Nation helps administer perhaps the most comprehensive programs currently in existence. The Navajo AIDS Network, founded by Melvin Harrison, partners with the Gallup [New Mexico] Indian Medical Center to provide counseling and case management services to Navajo patients diagnosed with HIV. The group also offers testing and educational services.

The GIMC itself is a valuable resource: Geared explicitly toward tribal members, it works closely with both the Indian Health Service and traditional hataa’lii, or medicine persons, to provide comprehensive medical and spiritual healing for HIV and AIDS (as well as for any other illness, injury or condition).

The lack of awareness spurred the 2006-2007 Miss Navajo Nation, Jocelyn Billy, to make HIV/AIDS education and outreach the service program for her year in office. Ms. Billy connected with the young people, the group most at risk, and helped adults navigate the gaps between traditional ways and modern medical realities.

Admirable as such efforts are, they aren’t enough, of course. What’s needed is the sort of full-bore commitment to HIV/AIDS awareness in Indian Country that is seen in other public health contexts – for cancer, heart disease or illnesses that are not seen as belonging to some marginalized “other.” On March 14, the White House announced that President Obama has appointed Dr. Grant Colfax as the new director of the Office of National AIDS Policy.Colfax is widely regarded as a public health expert on HIV and AIDS. Now would be a good time to push him and his agency to expand their work to include culturally appropriate outreach, education and treatment among our Native populations.

The models are already there: Other programs are taking shape around the country. For a glimpse of some of the events currently planned for Native communities for the coming week, visit NHAAD.org’s site, which features a clickable map.

You can learn more about Kyle’s daily journey on the Red Road, living as an Indian with HIV, at The Positive Project.

By Meteor Blades

On March 11, 1824, the Bureau of Indian Affairs was established. That it was set up, without congressional authorization, as a division of the War Department explains the prevailing view at the time. In fact, Indian affairs had been handled by the War Department since 1789, having been during the Revolution and its aftermath in the hands of three commissioners who included Benjamin Franklin and Patrick Henry. Ironically, Secretary of War John C. Calhoun, who invented the BIA, appointed Thomas McKenney, a Quaker, as its first superintendent. McKenney had been Superintendent of Indian Trade from 1816 until 1822 when the 16-year-old trade program was abolished. Among other things, McKenney took to calling it the Office of Indians Affairs, a name that stuck until authority was transferred to the Interior Department 25 years later.

McKenney worked diligently to get the OIA made official. In 1829, Congress did so, establishing a budget and giving the president authority to appoint a Commissioner of Indian Affairs who reported to the Secretary of War and had responsibility for “the direction and management of all Indian affairs, and all matters arising out of Indian relations.”

McKenney was a great believer in “civilizing” American Indians but, during his six years at the OIA, he became a vigorous proponent of removing Indians to places west of the Mississippi River. The removed Indians included the Cherokee who had become so “civilized” that thousands of them were literate in their own language with its own alphabet when they were marched out of their homeland at gunpoint. McKenney lost his job in 1830 because another great believer in removing Indians when he wasn’t actively engaged in killing them-Andrew Jackson-disagreed with his view that “the Indian was, in his intellectual and moral structure, our equal.” McKenney was shocked when he later saw how brutal the murderous removals actually were in practice.

When the Interior Department was established in 1849, the OIA was moved out of the War Department and permanently named the BIA, as Calhoun had intended from the beginning. Over the next 18 years, much of its work related to distributing aid, including food, both to Indians who had been removed and were now starving in their strange new environments, and to others who had signed treaties providing annuities in exchange for great swaths of their land. Corruption was the rule of the day. Indian agents, who often bribed their way into office, cheated the tribes of what was due them in various ways, many of them becoming wealthy buying secondhand goods and wormy food with Washington’s allocated funds for the tribes and pocketing the difference.

A congressional investigation in 1867 made recommendations for modest changes, some of which were enacted. However, a proposal to remove the BIA from Interior and make it an independent agency failed. In 1869, President Ulysses S. Grant appointed his Civil War adjustant, Ely Parker (Seneca) as the first commissioner of the BIA with Native blood. For the next two years, under Grant’s “peace policy,” military conflict with the tribes was greatly reduced. But after Parker left office, that changed again. Indians were fought, defeated and corralled onto ever smaller pieces of land, often far from their home territory. By 1900, the BIA had effectively become tribal government for all intents and purposes.

Over the next century, the BIA was investigated, reformed and reorganized several times as Indian policy went from the devastating allotment period that led to the seizure of tens of thousands of acres of land, the reestablishment tribal governments under the New Deal, the termination policies of the 1950s and 1960s during which more land was taken, and the turn toward more tribal sovereignty in the ’70s and ’80s as a partial consequence of red militancy emerging out of the broader civil rights movement.

Today, the BIA remains at Interior and holds nearly 56 million acres of land in trust for 566 Indian tribes and Alaskan Natives. How that land gets exploited by non-Indians remains a major point of contention between the bureau and many tribes. The BIA also runs Indian schools and Indian child welfare. It provides funding and training for police forces, tribal courts, reservation road building and other operations in cooperation with tribal governments. Where once Indian employees were rare, they now make up the vast majority of the bureau’s workforce, which is headed by Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs Larry Echohawk (Pawnee). Having Indians in charge has not stopped many other Indians from continuing to call the agency the Bureau of Incompetence and Arrogance.

•••

Additional information about the BIA can be found in this diary by Ojibwa.

More below:

Oglalas Face Criminal Charges for Civil Disobedience Related to Canadian Tar Sands

By navajo

First Nations people in Canada and the United States have been in the opposition to the Keystone XL pipeline ever since builder TransCanada proposed it years ago. The 1661-mile pipeline is designed to carry bitumen from the Alberta tar sands deposits to Gulf Coast refineries in Texas where it can be turned into oil. Along with other foes, some Indians were arrested last summer during protests against the pipeline at the White House.

Earlier this month, Lakotas on the Pine Ridge Reservation in southern South Dakota stepped up their opposition by blocking a highway when two massive trucks headed for the tar-sands mines forced a reservation motorist to pull off the road. Several of them were arrested but they vow to keep up their opposition.

The blockade got underway March 5 after word reached Debra White Plume (Oglala)that trucks carrying unusual covered cargo were making their way down the relatively narrow reservation highway not built for such heavy vehicles. White Plume, who was arrested last year in the White House protests, and whom climate-change activist Bill McKibben calls his “hero,” went into action when she heard that “Calgary, Alberta, Canada” was written on the side of the trucks from the Trotan company. She wasted no time in rallying her people and rushing to intercept the trucks. While she was en route, social media and the local reservation radio station, KILI, went into action, calling all able- bodied people to show up and support the blockade.

or Grandma Marie, 92

(Oglala Lakota)

Nearly 75 people eventually arrived, including 92-year-old Marie Brush Breaker Randall (Oglala), who is called Grandma Marie by everyone on the reservation, and another revered elder, Renabelle Bad Cob (Oglala), who came in her wheelchair.

Grandma Marie, her given name is Oyate Akitapi Win-Nation Woman (Oglala), lives in Wanblee, the word for “eagle” in Lakota. Her work includes raising awareness about diabetes and teaching the Lakota language to the next generation of Oglalas at Crazy Horse High School.

Her eloquent statements to the tribal police about the reasons for the human blockade are documented in this video that has had over 23,000 views since March 6. She says the road traverses Lakota land and asks the truckers who gave them permission to drive through. Why, she asks, didn’t they take much-faster state roads? In fact, who can travel on reservation roads has been long established by the courts, and the truckers were within the law.

Video can be seen here: http://www.youtube.com/embed/9…

The truckers, who were bringing their cargo from Texas, told blockade leaders that they had not been told their designated route would take them through Indian Country. They produced papers showing they “…each carried a ‘treater vessel’ which is used to separate gas and oil and other elements. Each weighs 229,155 pounds [far more than the residential roads are built to handle] and is valued at $1,259,593…” White Plume says in the video that the truckers also told them that the corporate office in Canada and the state of South Dakota made a deal to save the corporation $50,000 per truck by driving through the reservation to avoid state weighing stations. Randall proposed that the reservation needs to set up its own weigh stations.

The prevailing attitude of the peaceful blockaders was we will not stand down whatever the cost.

After six hours, the tribal police showed up and asked everyone to leave. Five Lakota refused. So Alex White Plume, Debra White Plume, Andrew Ironshell, Sam Long Black Cat and Don Ironshell were arrested and charged with the only thing police could come up with, disorderly conduct. They were booked and released. Debra White Plume:

We stood our ground for our land, our treaty rights, our human rights to clean drinking water and our coming generations. We did this in solidarity with the First Nations people in Canada who are being killed by the tar sands oil mine, which is so big it can be seen from outer space, it is as big as the state of Florida. It didn’t matter where the heavy haul was going, either to the tarsands oil killing fields, or another oil mine, we didn’t want it crossing our lands, until the Tribal Police could get there and determine under whose authority they got onto the Reservation

The huge trucks could not be turned around easily, so they were escorted off the reservation by the tribal police.

After the blockade, Debra White Plume says the Associated Press incorrectly attributed to her statements about what she was told. She said the reporter wrote in a story that appeared in the Argus Leader and Rapid City Journal that “the truckers told the group they were heading to a Canadian oil field with empty containers for drinking water,” when the truckers actually told her they were carrying treater vessels. The AP article also said a spokesperson for TransCanada had denied the trucks or their cargo had anything to do with the tar sands or the pipeline.

People on other reservations are organizing and preparing to block future Trotan convoys if they try to transit through their reservations. This likely generated new charges against the previously arrested five Oglalas have been told they now face.

According to a posting on Andrew Ironshell’s Facebook page, tribal Attorney General Rae Ann Red Owl is compiling a list of as many as eight charges put together with FBI involvement. A trial date will be set sometime in the coming week. The five arrested protesters have been told not to speak with the media and not to return to the blockade site on the highway. They may travel to Wanblee, but cannot pass through, which is something Ironshell called “ironic, huh?” the blockaders now blocked. “Will the OST [Oglala Sioux Tribe] Tribal Court support the values of the community or the interests of a corporate US Congress and a foreign company – TransCanada?”

On March 7, Alex White Plume wrote that the acting chief judge of the OST will handle the case and that Judge Fred Cedar Face has been recused. This presents an issue of fairness, White Plume wrote, because Cedar Face knows Oglala customs and speaks Lakota but the acting chief judge, who is not Oglala, does not.

Meanwhile, next Thursday, President Obama will visit Cushing, Okla., a major hub of oil pipelines. TransCanada has been given the green-light to build the southern leg of the Keystone XL from Cushing to Texas refineries at Port Arthur. Many foes of Keystone view the president’s “welcoming” statement regarding that section of the pipeline as an indication he will approve the whole project once the company has provided an alternative route that avoids the ecologically fragile Sandhills of Nebraska, a major focus of the opposition to TransCanada’s original rejected application.

Dakota Descendants Seek Memorial for Largest U.S. Mass Execution

By Meteor Blades

This year marks the 150th anniversary of the largest mass execution in U.S. history. On Dec. 26, 1862, on the direct orders of President Abraham Lincoln, 38 eastern Dakota (Sioux) men were sent to the gallows in Mankato, Minn., the penultimate act in the six-week-long Dakota War of 1862, also known as the Sioux Uprising. The final act was the expulsion of the Dakota from Minnesota and the termination of their reservations in the state.

Now, direct descendants of those hanged that day want to establish a memorial to them in Reconciliation Park in Mankato. But the majority of the city council, after informally approving the memorial, retreated recently by tabling formal consideration. Calling up old language, one councilman spoke of the “hostility” in the words of a 1971 poem that supporters of the memorial want included on it. That poem, which the councilman called divisive and untrue had nothing to do with reconciliation, he said.

Like hundreds of conflicts in the Indian wars before and after, the 1862 Dakota resistance arose out of broken promises. Before the ink was dry on the 1851 Treaty of Traverse des Sioux, Congress had stricken the crucial Article 3. This guaranteed a strip of land 70 miles long and 10 miles wide on each side of the Minnesota River for a reservation. Instead, Congress bought the land for 10 cents an acre and annuities.

(Mdewakanton Dakota)

Soon the Dakota were confined to the strip on the south side of the river. Payment of annuities were often late when they weren’t diverted by greedy, unscrupulous Indian agents who had bribed their way into office. They stole from the Dakota by various means. By the late 1850s, deprived or their best hunting grounds, plagued by rough winters and failed crops, the starving Dakota became ever more dependent on government food distributions. These too were often late and, thanks to government contractors and agents, consisted of substandard goods when they arrived at all. The Dakota became increasingly incensed over land encroachments and the failure to enforce the treaty rights they had forced to exchange for money and goods.

The push into a smaller space was meant to force the Dakota to adopt a new way of life. Chief Big Eagle said many years later, “It seemed too sudden to make a change […] If the Indians had tried to make the whites live like them, the whites would have resisted and it was the same with many Indians.”

Though accounts of his specific words vary, storekeeper Andrew J. Myrick inflamed passions in August 1862, by remarking at a meeting where Dakota representatives sought to buy food on credit, “If they are hungry, let them eat grass.” Several days after the meeting, four hungry and enraged Rice Creek Dakotas took it out on five settlers near Acton, Minn. Those killings spurred Dakota chief Little Crow to call a council that chose to go to war. Soon after the fighting broke out, Myrick was found dead with grass stuffed in his mouth.

The conflict ultimately killed some 500 whites and an uncounted number of Dakotas, including the 38 who were hanged in December that year. At one point, thinking the uprising might be part of a Rebel conspiracy, President Lincoln pondered the option of freeing 10,000 Confederate POWs to fight the Dakota under Union commanders. Before that could happen, however, the war was over.

In late September, a five-member military commission was convened. On the first day, 10 Dakota were sentenced to death. So it went for six weeks, 393 cases, 323 convictions, 303 death sentences. Thanks to pleas from an episcopal bishop, Lincoln commuted the sentences of all but 39, and one additional man was later granted a reprieve. The day after Christmas, chanting their death songs, they marched single file onto the gallows in Mankato and were hanged. Seven months later, Little Crow – who had escaped to Canada before the trial but returned to Minnesota – was killed by a white settler who shot him for a $500 bounty. Little Crow’s scalp and skull were displayed in St. Paul and finally returned to his grandson in 1971.

Minnesota Gov. Rudy Perpich declared 1987, the 125th anniversary of the executions, a “Year of Reconciliation.” Out of that came Reconciliation Park in Mankato, where today there is a plaque and two sculptures, one of a Dakota “Winter Warrior” and one of a bison, both victims of the Manifest Destiny that generated the 1862 uprising in the first place.

But those sculptures aren’t enough for Vernal Wabasha (Dakota). She and others want a memorial in the park for those executed. “They have markers all along the road about our savage Indians attacking white people,” said Wabasha, who has been married to Ernest Wabasha, a hereditary Dakota chief, for 56 years. He is the sixth chief of that name. The third one was chief at the time of the executions. Said Vernell Wabasha: “These men fought for the Dakota way of life, trying to hang onto something, to hang onto this land for the future generations of their children and grandchildren. […] They weren’t savages like they’ve been depicted for so long,”

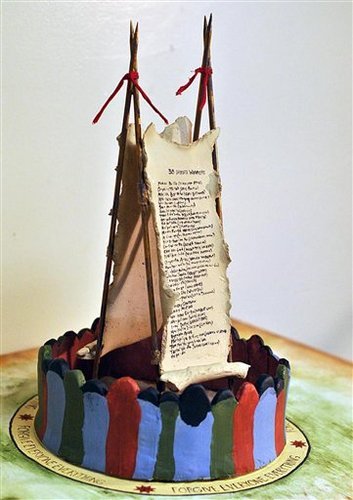

Designed by Linda Bernard and Martin Barnard (Dakota), the proposed memorial lists the 38 names on a 10-by-4-foot scroll. The phrase “forgive everyone everything” circles the monument, planned to be 20 feet in diameter. The names on one of the fiberglass scrolls will face south because the Dakota traditionally believe the spirits of the dead rise on the fourth day and travel south.

On the other scroll was to be a poem about executions written in 1971 by the state’s former human rights commissioner, Conrad Balfour. But that 20-line verse is what prompted the city council to back off endorsing the memorial two weeks ago. Among the criticized lines:

The day before the countryside had mourned the

death of Christ the Jew

Then went to bed to rise again to crucify the

captured Sioux […]

Then Captain Dooley cut the rope

38 was cleared of breath

Christmas day the children laughed and churches prayed the blessing set

In that town was 38 was blessed

Peace on earth good will to men

A few days after the council’s action, a bland new poem was written by Katherine Hughes that is more to the liking of at least some councilmembers:

Remember the innocent dead,

Both Dakota and white,

Victims of events they could not control.

Remember the guilty dead,

Both white and Dakota,

Whom reason abandoned.

Regret the times and attitudes

That brought dishonor

To both cultures.

Respect the deeds and kindnesses

that brought honor

To both cultures

Hope for a future

When memories remain,

Balanced by forgiveness.

While several councilmembers have said the new poem is acceptable, Vernell Wabasha is withholding judgment. Nothing is “chiseled in stone,” she said.

Cost of the memorial is estimated at between $55,000 and $75,000. Thus, if it is approved, fund-raising is next on the agenda. Wabasha, the Barnards and supporters of the project hope finished it by September, in time for the Mankato wacipi (pow-wow) gathering.

The names of the 38 who were executed:

Ti-hdo-ni-ca (One Who Jealously Guards His Home)

Ptan Du-ta (Scarlet Otter)

Oyate Ta-wa (His People)

Hin-han-sun-ko-yag-ma-ni (One Who Walks Clothed In Owl Feathers)

Ma-za Bo-mdu (Iron Blower)

Wa-hpe Duta (Scarlet Leaf)

Wa-hi-na (I Came)

Sna Ma-ni (Tinkling Walker)

Hda In-yan-ka (Rattling Runner)

Do-wan-s-a (Sings A Lot)

He-pan (Second Born Male Child)

Sun-ka ska (White Dog)

Tun-kan I-ca-hda ma-ni (One Who Walks By His Grandfather)

I-te Du-ta (Scarlet Face)

Ka-mde-ca (Broken Into Pieces)

He pi-da (Third Born Male)

Ma-kpi-ya (Cut Nose)

Henry Milord

Wa-kin-yan-na (Little Thunder)

Cas-ke-da (First Born)

Baptiste Campbell

Ta-te Ka-ga (Wind Maker)

He In-Kpa (The Tip Of The Horn)

Hypolite Ange

Na-pe-sni (Fearless)

Wa-kan Tanka (Great Spirit)

Tun-kan Ko-yag I-na-zin (One Who Stands Cloaked In Stone)

Ma-ka-ta I-na-zin (One Who Stands On The Earth)

Maza Kute-mani (One Who Shoots As He Walks)

Ta-te Hdi-da (Wind Comes Home)

Wa-si-cun (White Man)

A-i-ca-ga (To Grow Upon)

Ho-i-tan-in-ku (Returning Clear Voice)

Ce-tan Hu-nka (Elder Hawk)

Can ka-hda (Near The Woods)

Hda-hin-hde (Sudden Rattle)

Oyate A-ku (He Brings The People)

Ma-hu-we-hi (He Comes For Me)

Ancient Alutiiq Kayak to Revive Construction Knowledge

By navajo

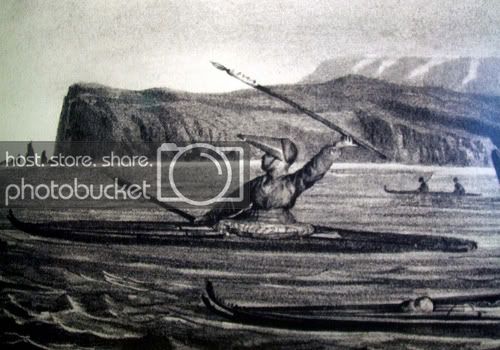

Alutiiq seal-skin kayaks were usually buried with their owners. But one dating back nearly a century and a half has been stored at Harvard’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology since 1869. Now, with help from two visiting Alutiiqs from Alaska – Alfred Naumoff, the last traditionally trained Alutiiq kayak-maker and seal-skin sewer Susan Malutin – researchers hope to learn more about the kayak and take efforts to preserve it before it is moved to the Alutiiq Museum on long-term loan.

When he was a teenager, Naumoff began to ask tribal elders about traditional kayak-making. On his trip to Cambridge he identified many components of the kayak that the researchers did not previously understand, such as that it had been made for a right-hander and that the craftspeople engaged in a long process to ensure the seal skins produced a light weight, yet extremely durable covering for the kayak.

For centuries, kayaks were central to the lives of the people of the southern Alaskan coast.

“I heard a reference that to insult somebody, you said, ‘Your father had no kayak,’” [Alutiiq Museum Director Sven] Haakanson said with a laugh. Alutiiqs used their kayaks to fish for porpoise, to hunt seals, whales and sea lions, as well as for traveling through the Aleutians and, at least once, as far as San Francisco, he said. “It was critical. Without having those skills to go out and kayak, you were going to starve. You couldn’t survive in Kodiak without that knowledge.”

The ancient Alutiiq way of hunting was replaced upon contact with Russian and European invaders who had modern boats and firearms. Assimilation and persecution took effect and traditional kayak-making, like language and other cultural elements, began a path toward extinction.

When the Peabody researchers complete their work, the kayak will be moved to the Alutiiq Museum. “It is hoped it can be used to invigorate the next generation’s interest in Alutiiq traditions and repatriate the knowledge,” Haakanson said.

h/t to GreyHawk

Youngest Iditarod Winner Ever Followed Trail of Ancient Alaskan Natives

By navajo and Meteor Blades

Part of what is now the Iditarod Trail was used by the Native American Inupiak and Athabascan peoples hundreds or more years before Russian fur traders began traveling that route in the 1800s. Now, it’s famous for the annual Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race. The 2011 winner was John Baker, a 48-year-old Inupiak, the first Native to win the race since 1976. It was his 15th Iditarod. His lead dogs were Velvet and Snickers. They, Baker and the other dogs on the team covered the race in 8 days, 18 hours, 46 minutes, 39 seconds, slicing three hours off the previous record.

That record was not eclipsed by this year’s winner of the 40th Iditarod, Dallas Seavey, from Willow, Alaska. At 25, Seavey is the youngest musher ever to win. His lead dogs were Guinness and Diesel. It took them 9 days, 4 hours, 29 minutes and 26 seconds to complete the grueling race. His father won the race in 2004. His grandfather, now 74, competed in the first Iditarod in 1972.

Two women, Libby Shaw and Susan Butcher, won the Iditarod in the 1980s. Butcher won four times, having lost her chance to become the first women to win in 1985 when her sled rounded a sharp turn and ran into a pregnant moose that killed two and injured five of her dogs. A woman, veteran musher Aliy Zirkle, came in second this year.

Drunken Indian Poster Celebrates Record Company’s Anniversary

By Meteor Blades

Jonathan Fischer wondered this past week whether the poster advertising a “Pow Wow Party” for Windian Records’ third anniversary had crossed the line.

Is that a Native American? With fangs and exaggerated features? And an intoxicated look? Yes, it is all of those things.

But is it racist? One Washington City Paper contributor thought so, and he let the label know via Twitter. To which Windian proprietor Travis Jackson tweeted back, with his usual caps-lock affect: “HOW IS IT RACIST? ITS JUST ART MAN. BESIDES, IM NATIVE, AND IM NOT OFFENDED…HOW ARE YOU?”

Jackson, former drummer of the garage band The Points, sometimes calls himself “Beeronimo,” claims his grandmother was a full-blooded Cherokee and “celebrate my heritage loudly, thru rock and roll music and art.” The Windian logo itself is a Plains Indian wearing a battered feather headdress and a puzzled expression. The fanged pow-wow drawing, which looks a lot like some now-abandoned sports-team logos, is typical, Jackson says, of the work of the artist, Ben Lyon. But Lyon’s work published on-line contains no fanged, besotted caricatures of other people of color. Nothing minstrelsy or lazy-Mexican-style.

Via email, Fischer asked Jackson what was up with the poster and he replied: “Its rock and roll. Its art. Its influenced from 50-60’s Rock N Roll art and culture. Its nothing new, its been done many times over.”

Yes, racist images are indeed nothing new and have been done plenty of times. You can still find wooden “cigar-store” Indians in front of small-town shops the way black lawn jockeys once populated so many front yards.

Ben Lyon himself wrote: “I know I’m not a racist. I think anyone offended enough to make a big stink over the art on a poster for a punk show, that they probably aren’t gonna attend in the first place, probably needs to get a life. Leave it to white American 20-somethings to see a neo-nazi lurking behind every tree.(ha ha!) Who says Indians can only be drawn as stern wisemen? Sounds like stereotyping to me! (ha ha) I would have no problem showing the poster to any of my Native American friends. I stand by my work.”

By March 14, Windian Records has replaced the show poster with a new one. Could “Beeronimo” have wised up?

• Last Fluent Speaker of ‘Kiksht’ Language Dies in Oregon: Gladys Thompson, (Wasco) 97, learned Kiksht from her parents and was also fluent in Ichishkiin and Sahaptin. Honored by the Oregon Legislature in 2007 for working to preserve the culture of the Wasco Tribe and keeping the Kiksht and Ichishkiin languages alive, Thompson also helped pass a bill to certify native language teachers. At the time she had 26 grandchildren, 78 great-grandchildren, and 23 great-great-grandchildren.

-navajo

• Larry Echo Hawk Receives the 2012 Governmental Leadership Award from NCAI: Echo Hawk (Pawnee) was appointed in May 2009 as assistant secretary for Indian Affairs, a position that oversees 10,000 employees in the Bureau of Indian Affairs and Bureau of Indian Education. The National Congress of American Indians, the nation’s oldest and most representative body of Indians, has made the award for the past 13 years. In 2011, it went to then-Associate Attorney General Tom Perrelli. Echo Hawk said: “The work we do at Indian Affairs is a rewarding experience in and of itself. It reminds me daily of my civic duty and loyalty toward my tribe, my people, my heritage, Indian Country and America.”

-Meteor Blades

• Native Youth and Young Adults Smoke the Most: A 920-page report released by the U.S. Surgeon General shows that American Indian youth (12-17) and young adults (18-25) are far more likely to smoke tobacco than any other racial/ethnic group in their age bracket. Nearly 50 percent of young adult Indians smoke. The only good news is that there has been a sharp drop in smoking among these cohorts over the past few years.

-Meteor Blades

• High-Tech Glass Helps Ojibwes Connect with Beauty of Ancestral Homeland: When the Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe built its new government center on the shores of the eastern Minnesota lake to which it has strong ancestral ties, it included large windows so tribal employees could enjoy the view and connect with the outdoors. But when the sun reflects off the water, they have to pull the blinds. Unhappy with that, the band installed SageGlass® in the nine south-facing windows in the wall of the conference room. The glass electronically (and automatically) tints itself and eliminates the need for blinds. The glare is eliminated but employees and visitors have an unobstructed view of the lake.

-Meteor Blades

• Sixteen-Year-Old Learns Ojibwe in 10 Days: Tim, who runs the YouTube channel PolyglotPal’s, has taught himself several languages via computer, including Russian, Pashto, two Arabic dialects, Hindi and the American Indian language Ojibwe. You can watch him speaking Ojibwe, or Anishinaabe (with subtitles) here.

-Meteor Blades

• Oregon May Ban Schools’ Use of Indian Nicknames for Their Teams: The state board of education has held hearings on whether to force 15 Oregon high schools to stop using Indian nicknames, logos and mascots for sports teams. About 20 schools dropped the usage in the 1970s, but the rest have hung on despite a 2007 recommendation that they be dropped. As elsewhere, some Indians support the ban; others do not. One Indian on the state board, Chairwoman Brenda Frank (Klamath), wants to see the nicknames go. Numerous studies cited by the American Psychological Association say the names, logos and mascots give Indian children a negative self-image. According to psychology professor Andrae Brown, who testified before the board, the use of the nicknames and associated material “undermines the ability of American Indian nations to portray accurate and respectful images of their culture, spirituality and traditions.”

-Meteor Blades

• A New TV Series, Navajo Cops premieres on National Geographic Channel: Perhaps the most unusual “cops” series yet, the 17-million-acre reservation is the main challenge the tribal police face, but the scenery shots are a bonus. Officers with traditional views are featured. One policeman washes himself with bitter herb for protection, and many on the force take calls about witchcraft seriously. Clips can be seen here.

-navajo with a h/t to Ed Tracey

• Bald Eagle Kill OKed for Northern Arapaho Tribe Under pressure from a lawsuit, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has given an extremely rare approval for kill two bald eagles for religious purposes by the Northern Arapaho of Wyoming. The Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act forbids killing the eagles or possession of any parts of the birds by non-Indians. American Indians can apply to obtain eagle feathers or carcasses from a federal repository in Colorado to use in ceremonies. The law also allows them to apply for permits to kill bald eagles, but permission has never previously been given. In testimony in 2007 regarding a member of the tribe who had killed an eagle and was being prosecuted for it, Nelson P. White Sr. (Northern Arapaho) said that birds obtained from the repositories were often rotten: “That’s unacceptable. How would a non-Indian feel if they had to get their Bible from a repository?” The USFWS permit states that the tribe may kill or capture and release the birds after the ceremony. Members of the Eastern Shoshone tribe, who share the Wind River Indian Reservation with the Northern Arapaho, oppose the killing of the birds.

-Meteor Blades

Indians have often been referred to as the “Vanishing Americans.” But we are still here, entangled each in his or her unique way with modern America, blended into the dominant culture or not, full-blood or not, on the reservation or not, and living lives much like the lives of other Americans, but with differences related to our history on this continent, our diverse cultures and religions, and our special legal status. To most other Americans, we are invisible, or only perceived in the most stereotyped fashion.First Nations News & Views is designed to provide a window into our world, each Sunday reporting on a small number of stories, both the good and the not-so-good, and providing a reminder of where we came from, what we are doing now and what matters to us. We wish to make it clear that neither navajo nor I make any claim whatsoever to speak for anyone other than ourselves, as individuals, not for the Navajo people or the Seminole people, the tribes in which we are enrolled as members, nor, of course, the people of any other tribes.

Leave a Reply