Interest in a scientific understanding of the history of North America prior to the European invasion and a desire to obtain legislation to protect our ancient heritage from looting and vandalism began to coalesce in the late nineteenth century with the formation of several groups and government agencies. The groups included the Archaeological Institute of America, the American Association for the Advancement of Science, and the Anthropological Association of Washington (which would later become the American Anthropological Association). The primary government agency concerned with antiquities was the Smithsonian’s Bureau of Ethnography.

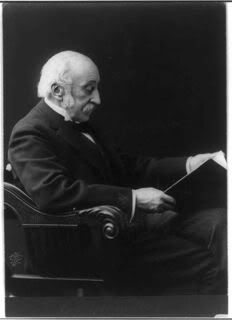

In 1879, the Archaeological Institute of America was established by Charles Eliot Norton, a professor of art history at Harvard, and a group of his friends. The purpose of the Institute was to promote and direct archaeological research, both classical archaeological research and research in the Americas. With regard to the Americas, it was felt that an understanding of aboriginal America was essential to the understanding of humans and it was important to understand the human conditions on this continent prior to the European discovery.

Charles Eliot Norton is shown above.

With regard to American archaeology, the Institute turned to Lewis Henry Morgan for advice and assistance. By 1898, the Institute had affiliated groups in Philadelphia, Chicago, Detroit, Minneapolis, Madison, Pittsburg, Cincinnati, Cleveland, and Washington, D.C. The members of these groups generally came from influential circles and therefore had significant influence on Congress and on Congressional concern for preserving antiquities.

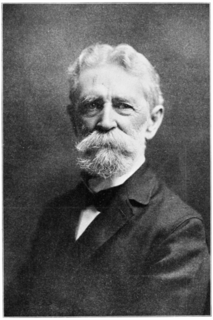

Frederic W. Putnam of the American Association for the Advancement of Science helped establish a committee to work for legislation to protect antiquities on federal lands. In 1894, Putnam was placed in charge of the anthropology program of the American Museum of National History in New York City.

Frederic W. Putnam is shown above.

In 1879 Professor Otis T. Mason of Columbian College and others assembled at the Smithsonian Institution and founded the Anthropological Association of Washington which would later become the American Anthropological Association. The AAA provided crucial support for the American Antiquities Act in 1906.

Otis T. Mason is shown above.

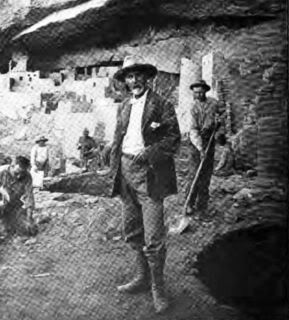

Noting the destruction of ancient sites in the Southwest, Dr. J. Walter Fewkes wrote in 1896:

If this destruction of the cliff-houses of New Mexico, Colorado, and Arizona goes on at the same rate in the next fifty years that it has in the past, these unique dwellings will be practically destroyed, and unless laws are enacted, either by states or by the general government, for their protection, at the close of the twentieth century many of the most interesting monuments of the prehistoric peoples of our Southwest will be little more than mounds of debris at the bases of the cliffs. A commercial spirit is leading to careless excavations for objects to sell, and walls are ruthlessly overthrown, buildings town down in hope of a few dollars’ gain. The proper designation of the way our antiquities are treated is vandalism. Students who follow us, when these cliff-houses have all disappeared and their instructive objects scattered by greed of traders, will wonder at our indifference and designate our negligence by its proper name. It would be wise legislation to prevent this vandalism as much as possible and good science to put all excavation of ruins in trained hands.

J. Walter Fewkes is shown above while working at Mesa Verde.

In 1901, Dr. Walter Hough, working in northeastern Arizona for the National Museum, wrote:

“The great hindrance to successful archaeologic (sic) work in this region lies in the fact that there is scarcely an ancient dwelling site or cemetery that has not been vandalized by ‘pottery diggers’ for personal gain.”

In 1899, the American Association for the Advancement of Science established a committee to promote a bill in Congress for the permanent protection of aboriginal antiquities on federal lands. At this same time the Archaeological Institute of America established a Standing Committee on American Archaeology. The two committees combined their efforts to seek preservation of American antiquities.

In 1902, the Records of the Past Exploration Society was formed and started publishing a journal, Records of the Past. The new society recommended the establishment of a national antiquities law. In 1904, the journal’s editor Rev. Henry Mason Baum, whose primary interest was in Biblical Archaeology, testified before the Senate:

“…two years ago I visited the mounds of the Mississippi Valley and the more important pueblo and cliff ruins of the Southwest. One of the objects I had in view was to ascertain how the antiquities on the Government domain could best be protected.”

Baum and his associates prepared a draft of a bill intended to preserve America’s antiquities. The bill, introduced by Representative William Rodenberg of Illinois, would place all historic and prehistoric ruins, monuments, archaeological objects, and antiquities on the public lands in the custody of the Secretary of the Interior with authority to grant excavation and collecting permits to qualified institutions.

In 1904, Senator Shelby M. Cullom and Representative Robert R. Hitt, both of Illinois, introduced bills which had been carefully worked out by the Smithsonian Institution. These bills defined antiquities as:

“…mounds, pyramids, cemeteries, graves, tombs, and burial places and their contents, including human remains; workshops, cliff dwelling, cavate lodges, caves, and rock shelters containing evidence of former occupancy; communal houses, towers, shrines, and other places of worship, including abandoned mission houses or other church edifices; stone heaps, shell heaps, ash heaps, cairns, stones artificially placed, solitary or in groups, with or without regularity; pictographs and all ancient or artificial inscriptions; also fortifications and enclosures, terraced gardens, walls standing or fallen down, and implements, utensils, and other objects of wood, stone, bone, shell, metal, and pottery, or textiles, statues and statuettes, and other artificial objects.”

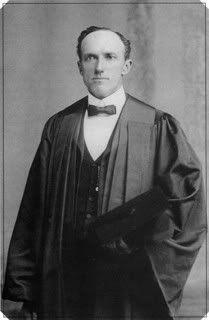

Following the conflicts between the two bills in Congress-one championed by Baum and the other championed by the Smithsonian), Commissioner W. W. Richards of the General Land Office had Edgar Lee Hewitt, the former president of New Mexico Normal University, review the entire antiquities preservation problem on federal lands. Hewitt had done archaeological work in the Southwest and was active in the American Anthropological Association. He studied at the University of Geneva in Switzerland and received his Ph.D. in anthropology. Hewett’s unusual combination of western background, farming and teaching experience, first-hand knowledge of ancient ruins on federal lands in the Southwest, and experience as an archaeologist and administrator, enabled him in this period to enjoy alike the confidence of members of Congress, bureau chiefs, staffs of universities and research institutions, and members of professional societies. Hewitt produced a memorandum which provided the Land Office and Congress with a detailed description of the antiquities in Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, and Utah. Following Hewitt’s recommendations Representative John Fletcher Lacey of Iowa and Senator Thomas M. Patterson of Colorado introduced new legislation to preserve American antiquities.

Edgar Lee Hewitt is shown above.

In 1906, Congress passed an Act for the Preservation of American Antiquities which makes it a criminal offense to appropriate, excavate, injure, or destroy historic or prehistoric ruins or objects of antiquity located on federal lands. The bill was motivated in part by reports of looting in the Southwest, particularly at sites such as Chaco Canyon, as well as by an increasing interest in the indigenous past of North America. The bill also reflected President Theodore Roosevelt’s passion for conserving and studying natural history, protecting America’s past, and ensuring continued access for a fast-growing scientific community.

As with most legislation regarding American Indians, there was no Indian involvement in the creation of the bill, no testimony by Indian leaders. There was, in fact, no suggestion that Indian people might have any legitimate affiliations with the past. There was still a strong feeling among politicians and among academics that Indian people were a disappearing people and that they were supposed to have vanished by the twentieth century. The fact of their continuing presence did not deter many non-Indians from assuming that they no longer existed.

In addition, many people still felt that Indian people had never been capable of great civilizations and thus the great ruins which were found throughout the Americas must have somehow been built and/or designed by non-Indians. A century later, people would be crediting aliens from other planets with many of the works done by American Indians.

There was no concern that living American Indians might have religious, spiritual, or historic connections to the sites which were to be preserved under the Antiquities Act. With the Antiquities Act, Congress declared that the American Indian past belonged to the general public in the same way as Yellowstone National Park. It was now the responsibility of the federal government, not the Indians, to protect and interpret the nation’s archaeological and historical resources. Under the permit system stemming from this act, protection and interpretation of the American Indian past was given to the scientific community rather than to the people whose ancestors had been responsible for its creation.

Under the Antiquities Act, amateur access to America’s past-whether by Indians or non-Indians-was now prohibited. Permission to examine ruins, excavate archaeological sites, or gather objects of antiquity is limited to people who were deemed

“properly qualified to conduct such examination…for the benefit of reputable museums, universities, colleges, or other recognized scientific or educational institutions.”

Human remains of Indians who had been interred on what were now federal lands were to be considered archaeological resources and thus were federal property. As federal property these human remains were to be stored in facilities for further research.

It has now been more than a century since the passage of the Antiquities Act. The looting and vandalism of American Indian sites has continued on federal lands, state lands, and private lands. With regard to the preservation of antiquities, the United States Congress, in its infinite wisdom, has passed the National Historic Preservation Act (1966), the Archaeological Resources Protection Act (1970), the American Indian Religious Freedom Act (1978), and the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (1990). Indians now have more of a voice in protecting their past.

Leave a Reply