Welcome to the third edition of First Nations News & Views. This weekly series is one element in the “Invisible Indians” project put together by navajo and me, with assistance from the Native American Netroots Group. Each Sunday’s edition is published at 3:30 p.m. Pacific Time, includes a short, original feature article, a look at some date relevant to American Indian history, and some briefs chosen to show the diversity of modern Indians living both on and off reservations in the United States and Canada. Last week’s edition is here.

| Cross Posted at Daily Kos |

70 Years Ago This Month the Navajo ‘Code Talkers’ Were Born

Joe Morris Sr. walked away from us on July 17. Keith Little walked away from us on Jan. 3. Jimmy Begay walked away from us Feb. 1. They were Navajo “Code Talkers,” three of the tribe’s 421 warriors who enlisted in the U.S. Marines to learn how to give Japanese intelligence headaches. Only a handful of those who joined up in the early months of 1942 remain and will soon also “walk away from us,” a common Navajo expression for dying. On Jan. 29, the last surviving member of the original 29 enlistees, Chester Nez, celebrated his 92nd birthday. Without them, their commanders and other officers have said, American casualties in battles for Japanese-held islands would have been far more ghastly than they were.

Those 29 and all the other Code Talkers were sworn to secrecy in case the code had to be used again. It was, in Korea and Vietnam. It was never broken. In 1968, the code and the story of its crucial role were declassified, freeing those who invented and used it to tell their experiences. Since then, more than 500 books have been written, several documentaries have been produced, Hollywood made a version called Windtalkers, a film that spends more of its time following Nick Cage around than it does Adam Beach (Saulteaux), who for his role spent six months learning Diné, the Navajo language. Famed sculptor Oreland Joe (Navajo-Ute) created the Navajo Code Talker Memorial at the Navajo Tribal Park & Veterans Memorial at Window Rock, Ariz. Oral histories were taken.

Yet, although President Ronald Reagan declared Aug. 14, 1982, National Navajo Code Talkers Day, it wasn’t until Dec. 21, 2000, 56 years after they first saw action, that the five surviving original Code Talkers and relatives of the other 24 received Congressional Gold Medals for their innovativeness and heroism. The other Code Talkers were awarded Congressional Silver Medals. The belated awards contained a deep irony. Many of these men who had saved untold numbers of American lives by using their native language had been punished for speaking that same language as children in boarding schools.

It may come as a surprise to many who are acquainted with the story of the Code Talkers that the Navajos weren’t the only Indians used for code work during World War II. And they weren’t the first. The Army even used eight Chocktaw speakers to confuse German troops in 1918. In the the next war, the Army in both the Pacific and Europe used Lakota speakers, Oneidas, Chippewas, Pimas, Hopis,Choctaws, Sac and Fox and Comanches. But those Indians simply talked to each other in their Native language. The first 29 Navajo Code Talkers developed a real code. They could not even be understood by other speakers of Navajo.

The Marines had never used Indians for this purpose. But Philip Johnston, a white man who had grown up on the lands of the Navajo Nation, approached the Corps in mid-February with an idea. Why not use Navajos and members of other large tribes for military communications? Show us, the Marines said. So Johnston brought four Navajos with him to Camp Elliott, Calif., for a demonstration. They were given some military messages. They substituted some Navajo words and then, in pairs, went into separate rooms and communicated by radio. Gen. Clayton Vogel witnessed the success, the decoded messages were accurate renditions of their English originals. He recommended to his superiors that 200 Navajos be recruited.

It took some high-level meetings before a decision was made. But, in April, a pilot program was initiated and in May 29 of the 30 Navajos recruited showed up at Camp Pendleton near Oceanside, Calif., for seven weeks of basic training. They came from places named Chinle, Kayenta, Blue Canyon and Kaibeto. Many had never before been off the reservation.

|

They developed a dictionary with words for military terms and then they memorized them. The Navajos could encode, transmit and decode a three-line English message in 20 seconds. Machines of the era took 30 minutes to do the same thing. Before the code, the fluent-in-English Japanese intercepted and deciphered codes easily. The Americans developed complex code, but these took a long time to decode, which could cost lives.

Initially, the Navajo code comprised about 200 assigned words, but by the end of the war, there were 800. Here is a small sample from the many to be found at Official Website of the Navajo Codetalkers:

Dive Bomber – Gini – Sparrow Hawk

Torpedo Plane – Tas-chizzie – Swallow

Observation Plane – ine-ahs-jah – Owl

Fighter Plane – Da-he-tih-hi – Hummingbird

Bomber Plane – Jav-sho – Buzzard

Patrol Plane – Ga- gih – Crow

Transport Plane – Astah – Eagle

The code was more complicated than mere word substitutions. The fear was that some sharp Japanese linguist might catch on to that soon enough. So words also could be spelled out using Navajo words representing individual letters of the alphabet. The Navajo words “wol-la-chee” (ant), “be-la-sana” (apple) and “tse-nill” (axe) all stood for the letter “a.” To say “Navy” in Navajo Code, they could say “tsah (needle) wol-la-chee (ant) ah-keh-di- glini (victor) tsah-ah-dzoh (yucca).” Thus, using assigned words or the alphabet code, they could encrypt anything. By not repeating the same word all the time for the same letter, they made it next to impossible to crack the code. In fact, it never was.

Navajo code talkers were on the ground with their fellow Marines in every major action in the Pacific from 1942 to 1945. They proved their value at Guadalcanal, at Tarawa and at the 36-day siege on Iwo Jima. After that immensely bloody battle, Major Howard Connor, a 5th Marine Division signal officer, said: “Were it not for the Navajos, the Marines would never have taken Iwo Jima.” He had commanded six Navajo code talkers during the first two days of the battle. They sent more than 800 messages, all without error.

Their participation went unsung for decades because of the secrecy. The world they returned to was not unlike the one they left. Federal policies which had improved somewhat during the New Deal era again focused on assimilation and terminating reservations. Many returning veterans were denied the right to vote even though they had supposedly been made full citizens by the Snyder Act in 1924.

Like other veterans of World War II, most of these men, many of them teenagers when they enlisted, have already walked away from us. The death of Keith Little leaves a big hole because, as a long-time leader of the Navajo Code Talkers Organization, he was the powerhouse behind the National Navajo Code Talkers Museum & Veterans Center project:

The museum is dedicated to the overarching purpose of providing historical clarity, accuracy and context in preserving the extraordinary contribution of the Navajo Code Talkers for future generations. Their story will be told in compelling detail through an immersive learning environment, powerful interactive exhibits and activities, living demonstrations of the Navajo code and culture in the larger perspective of modern history. The museum and integrated education programs will serve as the national repository for the once-secret military voice code and the legendary skill, endurance, courage and ingenuity of the Navajo Code Talkers.

The project also will include a veterans center for all Armed Forces veterans and active-duty personnel.

New Mexico State Sen. John Pinto has introduced a bill in the legislature there to appropriate $175,000 for the project. In October, just two months before he died, Little testified in Santa Fe before the Senate’s Military & Veterans Affairs Committee seeking to revive the bill, which was languishing. The bill received a unanimious “DO PASS” from the Indian and Cultural Affairs Committee on the last day of January and has been forwarded to the Finance Committee.

Donations to support the Museum & Veterans project that Mr. Little envisioned and was very much committed to can be made through the website: www.navajocodetalkers.org or by contacting Wynette Arviso at 505-870-9167 or via email wynette@navajocodetalkers.org.

The Code Talker Emblem

The emblem of the Code Talker represents a communication device used by two young Navajo boys called the Hero Twins. The device allowed them to secretly communicate with each other. The legendary Hero Twins were sent to the Sun to seek a weapon that would kill the monsters attacked the Navajo. The Sun gave them the Thunderbolt.

The Code Talker emblem and is also pictured on the reverse side of the Congressional Gold and Silver Medals.

This Week in American Indian History in 1890

The Indians must conform to the “white man’s ways” peaceably if they will, forcibly if they must. They must adjust themselves to their environment, and conform their mode of living substantially to our civilization. This civilization may not be the best possible but it is the best the Indians can get.

-(Bureau of Indian Affairs Report, 1889)

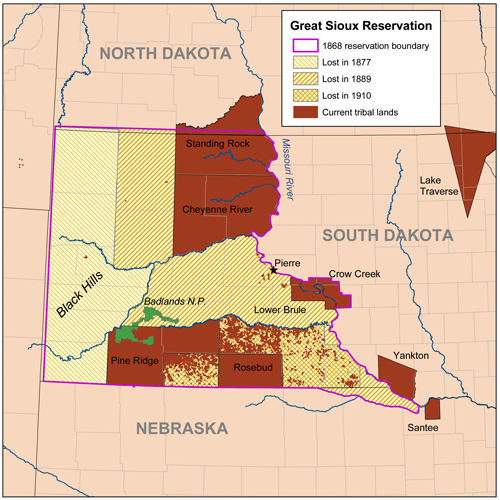

On February 11, 1890, half of the land on the five reservations making up the remnants of the Great Sioux Reservation was opened up to the public, continuing what was by then already a 40-year-old process that would continue to shrink Lakota tribal lands well into the 1960s. Both the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851 and later Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 reduced the area in which the Lakotas (and other tribes) were allowed to live. But, everything to what is now the boundary between Wyoming and South Dakota lying west of the Missouri River, including the sacred Black Hills, was to be theirs forever. Years of government pressure had failed to persuade many Lakota to stay within the reservation boundaries. This was especially true of the Oglala and Hunkpapa, whose chief and holy man, Tathanka Iyotake (Sitting Bull), had refused to sign the 1868 Treaty or live on the designated lands.

Click

for a larger version of this map.When a thousand soldiers under George A. Custer confirmed the presence of gold in the Black Hills in 1874, a deluge of miners staked claims on reservation land, which led to repeated clashes. Those clashes and refusal of thousands of Lakota to keep to the reservation ended in the Battle of the Greasy Grass (Little Bighorn River) in June 1876, a Pyrrhic victory for the Lakota. Just four months after Custer and his men died in Medicine Tail Coulee, Washington imposed the Treaty with the Sioux Nation of 1876. Under the provisions of the 1868 treaty, terms could only be changed with approval of three-fourths of Lakota adult men. Nowhere near that number signed in 1876. But the treaty was imposed anyway, stripping away a 50-mile-wide swath of land in what is now western South Dakota, including the Black Hills.

Preparing for statehood, Dakotans lobbied Washington for a cutting up of what was left of the Great Sioux Reservation into smaller reservations, grabbing nine million acres and opening land to homesteaders. In 1888, a federal commission sought to collect signatures from three-fourths of Lakota adult males. They were unsuccessful. The next year, they stepped up the pressure but still the Lakota refused to assent. Spokesmen John Grass, Gall, and Mad Bear opposed it, and though not chosen by his people to speak, Sitting Bull did speak and urged everyone to not be intimidated into signing away the land.

But enough signatures were obtained and, in 1889, Congress passed the Sioux Bill, opening the reservation to non-Indians and making acreage allotments to individual Indians with the intent of breaking up tribal land held in common and ending reservations entirely. Non-violent resistance continued after the law took effect in February 1890. Consequently, Sitting Bull was murdered during an arrest in mid-December and the infamous massacre at Wounded Knee came two weeks later. After that, resistance ended. More land was taken in 1910.

Many non-Lakota homesteads were abandoned in the 1930s, but instead of restoring these lands to the tribes, Washington turned them over to the National Park Service and the Bureau of Land Management. Even more land was taken for the Badlands Bombing Range during World War II. When the Air Force declared it was unneeded in the 1960s, it was transferred to the NPS instead of being returned to communal tribal ownership.

-Meteor Blades

|

South Dakota May Adopt Flag with Medicine Wheel Motif

Rep. Bernie Hunhoff, one of the 24 Democrats in the 105-member South Dakota legislature, is sponsoring a bill to choose a new flag that is different from the state seal. The one he has in mind was designed Dick Termes in 1989 for the 100th anniversary of South Dakota’s admission to the Union. It’s flashy and contains a stylized medicine wheel inside a sunburst. Medicine wheels are also known as sacred hoops. As described in a June 2007 article in Indian Country written by Dennis Zotigh (Kiowa, Santee Dakota, Ohkay Owingeh Pueblo)

The hoop is symbolic of “the never-ending cycle of life.” It has no beginning and no end. Tribal healers and holy men have regarded the hoop as sacred and have always used it in their ceremonies. Its significance enhanced the embodiment of healing ceremonies.

The best known medicine wheel is the 300-400-year-old, Indian-constructed 80-foot stone circle in the Bighorn Range in Wyoming.

Termes’s creation was forgotten 23 years ago. But he recently posted it on his Facebook page. And, in yet another example of how social media can turn obscurity into fame overnight, his design could soon be flying over public buildings everywhere in South Dakota. So, in a state known for the rapacity of the Indian wars fought on its soil, in the land of the Black Hills whose ownership is still in dispute, a place where ferocious anti-Indian racism still thrives in voter suppression and a hundred other ways, a new flag may soon incorporate a Native design as an expression of what Hunhoff calls a symbol of unity.

Bison rancher Ed Iron Cloud, III (Oglala), one of three Indian representatives in the legislature, said such a flag might show unity and coexistence.

– Meteor Blades

|

Menominee 7th Grader Suspended for Speaking Her Native Language

The student body at Sacred Heart Catholic Academy in Shawano, Wisc., is more than 60 percent American Indian and the Menominee reservation is just six miles away. Twelve-year-old Miranda Washinawatok (Menominee) was having a casual conversation with her Menominee friends, as were many other groups in their home room class while the teacher, Julie Gurta, worked on progress reports. Washinawatok, who is fluent in her native language, translated “hello” into “posoh” and “I love you” into “Ketapanen” for her friends. Gurta abruptly walked up to the group, slammed her hand onto Washinawatok’s desk and said: “You are not to be speaking like that. How do I know you’re not saying something bad and how would you like it if I spoke Polish and you didn’t understand.”

Gurta had told the group once before that they could not speak Menominee. She did not ask what the girls were saying. Later, another teacher told Washinawatok that she did not appreciate her upsetting Gurta because “she is like a daughter to me.” By the time school ended Washinawatok had been informed by Assistant Coach Billie Joe Duquaine, a preschool teacher at the school, that she was suspended from the next basketball game because of an “attitude issue.” Washinawatok told her mother she had not talked back, argued with Gurta or otherwise behaved badly.

According to Tanaes Washinawatok, Miranda’s mother: “Miranda knows quite a bit of Menominee. We speak it. My mother, Karen Washinawatok, is the director of the Language and Culture Commission of the Menominee Tribe. She has a degree in linguistics from the University of Arizona’s College of Education-AILDI American Indian Language Development Institute. She is a former tribal chair and is strong into our culture.”

Washinawatok’s mother and Tribal legislators Rebecca Alegria and Orman Waukau Jr. met with Principal Dan Minter and the teachers. A verbal apology was given to Washinawatok and a public apology was promised.

However, the letter sent home with students was not the agreed-upon apology to Washinawatok, the family and the Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin.

Principal Dan Minter, however, instead sent students home Wednesday with a letter addressed to Sacred Heart’s parents and families. In it, he apologized for allowing a “perception” of cultural discrimination to exist, but denied the reprimand and benching – which are not mentioned specifically – were the “result of any discriminatory action or attitude and did not happen as a negative reaction to the cultural heritage of any of our students.” […] Minter said the incident was the result of “a breakdown of our internal processes designed to offer protection to student, faculty, staff, volunteers and administrators.”

“I regret if there was any perception by a student or family that this in any way promoted an atmosphere of cultural discrimination,” he said in the letter. “If that perception was allowed to exist, then it is deeply regretted by Sacred Heart School and for that we apologize.”

Sacred Heart Catholic School was established in November 1881. One hundred thirty-one years later, it is finally creating a awareness program to promote cultural diversity, which will include education for both the students and staff.

News & Views h/t to Bill in MD

– navajo

|

Lansing Mayor Slurs Indians in Casino Dispute:

On one side are the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa (Ojibwe) Indians and the city of Lansing, Mich. On the other are the Saginaw Chippewa Indian Tribe and the Nottawaseppi Huron Band of Potawatomi Indians. The four are in a clash over a proposed $245-million casino in downtown Lansing, the state capital.

For Lansing, adding a local casino to the more than two dozen now operating in the state means an estimated 1,500 permanent jobs and 700 construction jobs and more tax revenue to help revitalize the city. For the Sault Ste. Marie Chippewas, it gives an off-reservation foothold from which to expand into southern Michigan, adding to the five Kewadin casinos the tribe owns on the state’s Upper Peninsula. For the Saginaws and the Nottawaseppis, it means competition for their casinos in Battle Creek and Mt. Pleasant and, in their view, is a violation of the Indian Regulatory Gaming Act (IGRA). For Lansing Mayor Virg Bernero (D), avidly in favor of the casino, it has meant getting a remedial lesson regarding racist outbursts.

At a fund-raising breakfast, Bernero showed up wearing a bulls-eye taped to his back, implying he is the target of arrows. According to people at the fund-raiser, he referred to James Nye (Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians), a spokesman for casino opponents, as “Chief Chicken Little.” That generated calls for apologies. Bernero obliged with one of those no-apology apologies to “any and all who were offended. […] but none of my remarks were directed toward Native Americans, and nothing I said can fairly be construed as a racial slur, despite our opponents’ attempt to spin it that way.”

In a statement from the two Tribes, Saginaw Chippewa Chief Dennis Kequom said Bernero’s presentation clearly was racial: “Racial slurs by government officials against Native Americans conjure images of a bygone era of destructive policies that resulted in centuries of genocide and poverty.” Kequom called on other Native American leaders-and particularly those of the Sault Tribe-to condemn Bernero’s actions. He also told the mayor to get some sensitivity training.

Under the plan, the tribe would buy land from the city to build the casino, which would need approval from the Department of the Interior. The Saginaws and Nottawaseppis issued a statement saying the casino “stands no chance under federal law and administrative rules governing land into trust acquisitions for ‘gaming eligible’ lands.” The statement was accompanied by a letter from Republican Gov. Rick Snyder, Atty. Gen. Bill Schuette and Philip N. Hogen, a former chairman of the National Indian Gaming Commission. Hogen said the Sault Tribe’s actions were an attempt “to circumvent the federal Indian Gaming Regulatory Act and applicable state laws against illegal gambling. […] The distant sites do not constitute ‘Indian lands,’ as defined by IGRA and therefore Michigan state gambling laws apply.”

– Meteor Blades

|

Houlton Band of Maliseet Indians to serve

in the Maine House of Representatives. In

his hand is the golden eagle feather he held

when he was sworn in by Gov. Paul LePage

last month. (Gabor Degre)

Maliseet Added to Maine’s Unique System of Tribal Representatives in the Legislature

He can’t vote in the Maine House of Representatives, but David Slagger of the Houlton Band of Maliseet Indians can make speeches, propose legislation with a co-sponsor and sit on committees. He is the first member of his 800-person band to be chosen as a tribal representative to the legislature since the state approved the position in 2010. The Maliseets were not federally recognized until 1980.

Slagger joins non-voting representatives from Maine’s two biggest tribes, the Passamaquoddy and the Penobscot nation. Both have sent representatives to the legislature for years. His cross-borders tribe is part of the larger Maliseet Nation of New Brunswick, Canada, and together with the Passamaquoddy, Penobscots, Abenaki and Mi’kmaq, form the Wabanaki Confederacy, which means people of the “dawn land.” Maine is unique among the states in having tribal representatives in its legislature.

Slagger told the Bangor Daily News that he has been involved in tribal issues for 25 years. “In public service, it is the people’s voice that matters,” he told a reporter. “But for a long time the Maliseet people have not had a voice. This is a good first step.” He was appointed by Chief Brenda Commander after interviews by the tribal council. For now Slagger has a seat on the Inland Fisheries and Wildlife Committee and sits in both the Democratic and Republican caucuses to get a good picture of what the issues are in the legislature. He has a couple of ideas for new laws. He would outlaw people from pretending to be Indians so they can sell arts and crafts and other Indian-branded products. He also wants the state to create a repository for bird feathers and allow Indians to use them in their crafts.

Slagger lives in Kenduskeag with his wife (a Mi’kmaq) and their three children. You can listen to some of his interviews here.

– Meteor Blades

|

Kootenai Get ETC Cards for Easier Border Crossings

As a consequence of the passage of the Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act of 2004, the Western Hemisphere Travel Initiative was enacted. This requires all travelers, including U.S. citizens, to present passports or other secure documents upon entering the United States. Technology, including Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) tags, are now being used to enhance identification documents and speed the processing of cross-border traffic.

Beginning in 2008, U.S. Customs and Border Protection began working with federally recognized Indian tribes to produce an “Enhanced Tribal Card” showing citizenship and identity that would be acceptable for entry into the United States. Under a memorandum of agreement, a secure photo identification document with embedded RFID verification would be issued to enrolled tribal members whether they were U.S. or Canadian citizens.

The Idaho Kootenai tribe, whose 142 members live on both sides of the U.S.-Canadian border, were the first to sign such a memorandum in 2009. The Idaho band is one of seven making up the Kootenai Nation. Their ETC officially became a valid form of I.D. to enter the U.S. on Jan. 31. So far, 11 other tribes have applied for an ETC memorandum of agreement. Besides the Kootenai, CBP has signed an agreement with five others: the Pascua Yaqui of Arizona, the Seneca of New York, the Tohono O’odham of Arizona, the Coquille of Oregon and the Hydaburg of Alaska.

Kootenai Tribal Chairperson Jennifer Porter said, “The Kootenai ETC allows our tribal citizens to continue to travel within Kootenai Territory on both sides of the United States-Canada boundary to visit family and practice our culture while helping to secure the border for the greater good of all citizens.”

– Meteor Blades

|

• Johnson Holy Rock, Prominent Lakota Language Preservationist Passes: A World War II veteran, Lakota Language Consortium founder and past Oglala Sioux Tribe president who met with John F. Kennedy in the White House has died. His grandfathers traveled with Crazy Horse and his father was 11 years old when Custer attacked the Lakota-Cheyenne encampment at the Little Bighorn. He was featured in A Thunder-Being Nation. In 2005, he recorded the telling his life story in Lakota.

– navajo

• Frybread Mockumentary Spoofs Importance of Which Tribe Makes the BEST: In the comedy More than Frybread, 22 American Indians, representing all federally recognized tribes in Arizona, convene in Flagstaff to compete for the first-ever Arizona Frybread Championship. The film has been selected to show at the Sedona International Film Festival and the Durango Independent Film Festival in 2012.

– navajo

• Tribal Identity Film Selected for Sundance: OK BREATHE AURALEE is writer/director Brooke Swaney’s (Blackfeet & Salish) NYU thesis film. It stars Kendra Mylnechuk (Inuit) and Nathaniel Arcand (Cree) with music composed by Laura Ortman (White Mountain Apache). A Native identity film about an adopted woman discovering her past was selected for the Sundance Film Festival 2012.

– navajo

• Daugaard’s Staff Attacks NPR Report on Indian Foster Care Scam: South Dakota Gov. Dennis Daugaard, who personally profited from placing Lakota children in non-indian foster homes calls the NPR report flawed and useless. But two members of the U.S. House of Representatives thought the NPR report was valid enough to call for an investigation.

– navajo

• Does Spam Cause Diabetes in Native Populations?: The researchers said that their study could not prove that eating processed meats was to blame for the increased risk of diabetes. I suspect highly refined carbs are also to blame since low income and need for long shelf life products are prevalent on our reservations.

– navajo

• National Marine Fisheries Service Sued For Not Protecting Our Northwest Coast: A coalition of conservation and American Indian groups filed a lawsuit against the National Marine Fisheries Service for failing to mitigate harm to marine mammals from U.S. Navy warfare training exercises along the coasts of California, Oregon and Washington.

– navajo

Indians have often been referred to as the “Vanishing Americans.” But we are still here, entangled each in his or her unique way with modern America, blended into the dominant culture or not, full-blood or not, on the reservation or not, and living lives much like the lives of other Americans, but with differences related to our history on this continent, our diverse cultures and religions, and our special legal status. To most other Americans, we are invisible, or only perceived in the most stereotyped fashion.First Nations News & Views is designed to provide a window into our world, each Sunday reporting on a small number of stories, both the good and the not-so-good, and providing a reminder of where we came from, what we are doing now and what matters to us. We wish to make it clear that neither navajo nor I make any claim whatsoever to speak for anyone other than ourselves, as individuals, not for the Navajo people or the Seminole people, the tribes in which we are enrolled as members, nor, of course, the people of any other tribes.

Leave a Reply