Welcome to the 20th edition of First Nations News & Views. This weekly series is one element in the “Invisible Indians” project put together by navajo and me, with assistance from the Native American Netroots Group. Our 19th edition is here. In this edition you will find “Sioux Seek to Rescue Sacred Black Hills Site from Auction,” a look at the year 1680 in American Indian history, five short features, and nine news briefs. Click on any of the headlines below to take you directly to that section of News & Views or to any of our earlier editions.

This Week in American Indian History in 1680

~ Elders Hold Native Community Together in Chicago ~

~ Remains of “Wild West” Performer Going Home After 112 Years ~

~ Cherokee Officials Ponder Raising Buffalo ~

~ Obama Signs the HEARTH Act of 2012 to Promote Tribal Self-Determination ~

By Meteor Blades

A 1942-acre slice of land sacred to the Lakota, Nakota and Dakota (Sioux) people goes on the auction block next Friday. It’s Pe’ Sla, known to some as “Old Baldy” and “peace at the bare spot” to others. It is one of five sacred sites that make up Lakota pilgrimage and ceremony, and it is closely linked to the constellations, an earthly reflection of the cosmos. It is the only one of the five sacred sites held in private hands-the rest being under federal or state control-and remains relatively pristine, acreage having been used only for grazing cattle over the past 130 years. But developments are closing in on other nearby private land.

Pe’ Sla is also called Wowakcawala Okislata, which means “purity of peace and harmony,” according to Leonard Little Finger (Oglala-Miniconjou). One tribeswoman has compared it to the Holy Sepulchre, to Mecca, to the Western (Wailing) Wall. Like other sites sacred to the Lakota, Pe’ Sla is in the Black Hills, the Páha Sápa. In Lakota, they are wahmunka oganunka inchante, “the heart of.” Pe’ Sla is at the center of Páha Sápa, the “center of the heart of” everything that is.

Nobody knows for certain what the buyers will do with each of the 300-acre parcels carved out of the land of 7,000-foot-high Pe’ Sla, but development of some sort is dead certain when investors purchase a property estimated by the auction house to draw up to $10 million in bids. The state of South Dakota has said it will build a road through the heart of the center of the heart.

It was only a few weeks ago that it was discovered that the property would be offered for sale. The Rosebud Sioux Tribe (Sicangu Oyate Lakota) is frantically working to raise funds so that it can make its own bid. To achieve this, it has put out a call to all the Oceti Sakowin, the people of the seven council fires of the Great Sioux Nation.

So far, $86,000 of the $1 million goal has been raised at a site dedicated to the Pe’ Sla purchase here. Rosebud has pledged another $50,000, and other Sioux tribes are pondering how much they will contribute to the cause.

Chase Iron Eyes (Standing Rock Sioux) presents the case:

Video will not embed at Soapblox:

http://www.youtube.com/embed/t…

The core of the property, the Reynolds Prairie, was homesteaded in 1876, the same year that George A. Custer saw his final action a few hundred miles west in Medicine Tail Coulee. That homestead was illegal since the land had been granted to the Lakota by the Treaty of 1868. But after word “leaked out” that gold had been found by Custer’s expedition in 1874 into the Black Hills, the flood of settlers and fortune-seekers became unstoppable. Among them were the ancestors of Leonard and Margaret Reynolds who own the land now and are putting it up for sale. Iron Eyes commended the couple for what good stewards they have been for that land and for granting Indians access. But the auction could mean the end of both.

In 1877, as part of the ferocious response to the Battle of the Little Big Horn, Congress unilaterally took the Black Hills. In a 1980 case, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that they definitely had been taken illegally against the provisions of the 1868 treaty. “Stolen” wasn’t a word the justices used, but it would have been accurate. The court awarded $100 million to the tribes as compensation.

But, year after year for three decades, they have refused to accept the money, now grown in a trust fund to more than $1 billion through compound interest. Those dollars could go a long way toward improving the lives of the tribes of the Great Sioux Nation, some of whom are among the most impoverished people in America. But they continue to say “the Black Hills are not for sale.” Ironically, Pe’ Sla, a piece that clearly is for sale, could be purchased for one percent of what’s in the Black Hills settlement trust.

Raising the money needed to make a reasonable bid on Friday for Pe’ Sla is, to put it mildly, an uphill struggle. Hopkins pointed out that today’s stereotypes of Indians making money in great gobs from casinos only applies to a few tribes. Most of the Lakota, Nakota and Dakota live in poverty. Raising millions of dollars to hang onto a piece of holy prairie turf is no easy matter for them. Nor is asking non-Indians to help them out. Yet, so important is the site to them, that they are doing so.

Ruth Hopkins (Sisseton-Wahpeton/Mdewakanton/Hunkpapa), who, together with Iron Eyes and a dozen others, writes at the Last Real Indians website, has laid out some of the spiritual meaning and temporal history of Pe’ Sla:

Not only does this sacred site play a key role in our creation story, it is said to be the place where The Morning Star plunged to earth, and saved the People from seven creatures who had killed seven women. The Lakota hero then placed those women in the night sky as “The Seven Sisters,” called “The Pleiades” by Western astronomers.

Pe’ Sla, also called “Old Baldy,” is vital to Oceti Sakowin star knowledge and provides evidence of our historical ties to the Black Hills as well. The Black Hills are a terrestrial mirror of the heavens above. Pe’ Sla, an open, rather bare expanse of land compared to its surroundings, corresponds to the Crab Nebula, a gaseous cloud remnant of a supernova explosion that happened in 1054 AD. It is no longer visible with the naked eye-but my people remember it.

If you wish to help, please note that all donations to the tribe are tax-deductible and will only be used toward the purchase of Pe’ Sla. You can contribute here.

By Meteor Blades

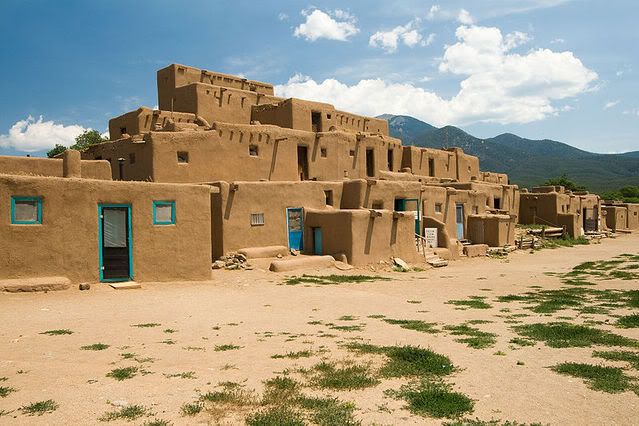

On August 21, 1680, Spanish colonialists fled their outpost in Ogha Po’oge, the Tewa Indian name for the town of Santa Fé in what was then the occupied territory of New Mexico, a northern province of New Spain. The town had been under siege for six days in the uprising we now call the Pueblo Revolt, or Popé’s Rebellion, so-called from the Spanish name for Ohkay Owingeh, the San Juan Pueblo leader who initiated the resistance that had begun 10 days earlier. Over the few weeks of the revolt, Popé and some 2,000 warriors of most of the northern pueblos as well as the Zuni and Hopi killed some 400 Spaniards and drove off 2,000 others from land they had first conquered eight decades previously.

Popé had promised that, with the Spanish gone, the old Pueblo gods would return and a decade-long drought would end.

Those gods hadn’t departed on their own. The Spanish, operating under their usual motivations of “gold, glory and God,” gained political and economic control over the estimated 40,000 Pueblo people in the area by establishing theocracies in the most of the 46 Pueblo towns. Resistance was brutal. Early on, Juan de Oñate, the New World-born conqueror ordered into New Mexico by the Spanish king, demanded supplies from the Acoma pueblo that they refused to provide. When he insisted, they resisted, killing 12 Spanish soldiers. De Oñate responded with an overwhelming show of force. Ultimately, 800 Indians were killed and 500 enslaved. He also ordered 24 to have one foot cut off.

The priests, integral to every Spanish expedition, were always gentle in their conversion efforts until Indians resisted the purported benefits of Roman Catholicism. Religious freedom not being part of their lexicon, suppression of the Native religion grew more ferocious as the years passed. The Spanish destroyed kivas, the subterranean ceremonial pits of the Pueblo, and banned the use of kachinas, their sacred ritual objects. Ceremonies were forbidden, medicine men incarcerated and murdered. Opposition was met with imprisonment, torture and more amputated limbs.

The Spanish also imposed the encomienda and repartimiento systems. These amounted to a form of forced labor only superficially different from slavery in that Indians were not owned outright. Individual Spaniards were given power over a specified number of Indians whom they made to work for little or no pay on farms or in mines or workshops. Punishment for disobedience often included death.

For three generations this continued. A mixed-blood mestizo population steadily expanded. The Indian population fell to around 15,000 as the Spanish population rose to about 2,500.

In the 1670s, one of the Southwest’s periodic droughts struck. The forced-labor system meant that Indians could not attend to their own food-tending needs at time when that was more necessary than usual. Famine ensued in some areas. This was exacerbated by Apache raids which the imperial Spanish protection racket was not much protection.

Scholars differ about the proximate causes of the revolt. Some argue that it was mostly religious and cultural oppression. And, indeed, giving some credence to this view is that 21 Franciscan priests were singled out to be killed. Others say, however, that the drought, forced-labor system and Apache raids were the chief motivations behind the rebellion.

One writer, a 20th Century U.S.-born priest named Angélico Chávez, claimed the world-view of the Pueblo combined with miscegenation and their partial acculturation by the Spanish was such that Popé himself was incapable of leading a revolt, prophet or no. Instead, Chávez claimed, the rebellion was the product of Domingo Naranjo, a “mulatto” able to move between the Pueblo and Spanish easily. Chávez wrote that Naranjo manipulated the Pueblo into believing he was Pohé-yemo, a leading figure in their religion who supposedly wanted them to revolt.

But another writer, Andrew L. Knaut, wrote in an essay, “Acculturation and Miscegenation: The Changing Face of the Spanish Presence in New Mexico,” that intermarriage and acculturation not only did not create harmonious relations but actually had helped spur the revolt. His view is that the Pueblos had more reasons to rebel than not.

Whatever the case, they did revolt and the Spanish did flee.

A dozen years later they were back under the leadership of Diego de Vargas. Sixty Spanish soldiers, 100 Zia converts and the inevitable priests marched into New Mexico again and quickly made their way to Santa Fé. Without a single shot fired from musket or cannon, de Vargas persuaded the Pueblo people barricaded there to surrender upon a promise of amnesty. He then retook formal possession for Spain. In 1693, however, many Indians were having second thoughts after a year of being ordered around, told what to believe and treated harshly under renewed Spanish dominance. Whan de Vargas returned with more soldiers, settlers and still more priests, a two-day battle raged. It ended in executions for 70 Pueblo men and a decade of slavery for the surviving rebels.

For a few years there was sporadic resistance that led to the Second Pueblo Revolt in 1696. De Vargas handled it with his usual merciless self. By the turn of the century, the Pueblo were fully subdued, partly because so many had fled to live with the Navajo and Apache.

While the two revolts themselves were crushed, the Pueblo people managed to gain for themselves a measure of religious freedom, their traditional beliefs being accommodated even as efforts to convert them to Roman Catholicism continued. They also obtained the land grants upon which they still live.

Major Sources:

• New Mexico Office of the State Historian-Juan de Oñate

• Sando, Joe. Pueblo Nations: Eight Centuries of Pueblo Indian History. Santa Fe, N.Mex.: Clear Light Publishers, 1992.

• Weber, David J. What Caused the Pueblo Revolt of 1680: Readings. Selected and Introduced by David J. Weber. Historians at Work Series. Boston: Bedford/St. Martins, 1999.

• The Spanish Re-Conquest of New Mexico and the Pueblo Revolt of 1696.

Elders Hold Native Community Together in Chicago

By Meteor Blades

in the late 1940s.

At 87, Susan Kelly Power (Standing Rock Sioux) is the oldest American Indian in the Chicago area. Her surname says a lot about her. She exudes power built on a life-time of activism and service. Power and respect and admiration.

She left the reservation that straddles North and South Dakota 70 years ago in the midst of World War II. It was a tough go at first. But her work for Indians began almost immediately. She is the last surviving founder of the National Congress of American Indians. The pan-Indian organization that began in 1944 and is now the largest representative non-governmental Indian organization in the country. Today she and a few other elders in Chicago strive to remind urban Indians of their heritage, involve themselves as activists in the greater community to break down stereotypes while making Indians more visible, and occasionally engage in a political battle.

“We want people to know that we still exist. We haven’t left this earth yet,” said Power, a historian and co-founder of the American Indian Center, a social services and cultural facility in Uptown that was once the anchor of the local Native American community. “But we don’t want people to look at us with pity in their eyes or romanticize us. Most of the material out there is nonsensical. It’s up to us to tell our story.”

Over time the center has seen fewer Indians seek its services and has opened its doors to other minorities and low-income people in general. But Mayor Rahm Emanuel cut the center completely out of the city’s budget this year, and it has had to struggle to find other funding.

Susan Kelly Power in 2011. As a little girl, Power’s family lived close to what was understood to be the grave of the Hunkpapa Lakota chief Sitting Bull. When a car of whites would be seen coming up the road in those 1930s days, her mother would send her and her sister to sit by the grave to keep anything from being stolen. Since then, she says she has followed in her mother’s footsteps as a driven advocate for the rights and well-being of Indians.

Susan Kelly Power in 2011. As a little girl, Power’s family lived close to what was understood to be the grave of the Hunkpapa Lakota chief Sitting Bull. When a car of whites would be seen coming up the road in those 1930s days, her mother would send her and her sister to sit by the grave to keep anything from being stolen. Since then, she says she has followed in her mother’s footsteps as a driven advocate for the rights and well-being of Indians.

“My mother was the first Native woman in the country to be in a leadership position,” Power said. “Once my mother was asked why she didn’t have one of the new homes being built on the reservation. She said, ‘When all my people have nice homes, then I’ll consider it.’”

When Power came to Chicago nearly seven decades ago, there were only about 200 Native Americans in the city, she said.

“We had no cars or telephones, but we managed to find each other and stick together,” she said. “If one got a job, we immediately did very well in it so that others could be hired too.”

That cooperative, all-for-one attitude has not always found a home among Indians, on or off the reservations, but it is the one that epitomizes what most activists today and historically.

Remains of “Wild West” Performer Going Home After 112 Years

By Meteor Blades

Amateur historian Robert Young has helped a family on the Cheyenne River Sioux Reservation of South Dakota bring home an ancestor who died 112 years ago in Connecticut and was buried in an unmarked grave. Young’s genealogical researched revealed that 20-year-old Albert Afraid of Hawk had traveled from New Haven as part of the famed Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show for a one-night show in Danbury. He died two days later from botulism after eating bad canned corn.

Before he retired, Young was an employee of the Wooster Cemetery where Afraid of Hawk was buried. In his research, Young discovered a July 6, 1900, article in the New Haven Register that reported on Afraid of Hawk’s death. Others also ate the bad corn and were treated at a local hospital in Danbury, but he was the only one who died. His grave was dug in a section of the cemetery set aside for indigents. Even though the grave has no marker, like thousands in the cemetery, it wasn’t that hard for Young to find because meticulous records were kept.

Young contacted Pine Ridge officials to help him track down descendants in Afraid of Hawk’s family. They turned out to be on the Cheyenne River Sioux Reservation. Later, he traveled there to meet with them. Four of them, including a nephew and grandniece, went to Connecticut last week and took part in a disinterment ceremony that ended Friday. Nicholas F. Bellantoni, the state archaeologist supervised the exhumation. Traditional Lakota rituals were performed as part of the disinterment.

“We are all so deeply grateful,” said Wendell Deer With Horns, 56, a distant cousin who lives in Watertown, Conn.

“You can feel Albert’s spirit right here,” he added, handing out rocks from Mr. Afraid of Hawk’s grave. “This is his eternal energy.” […]

John Afraid of Hawk, a grandnephew, blew an eagle-bone whistle, and [grandniece Marlis] Afraid of Hawk looked up. “There was a hawk,” she said. “That symbolizes to me that he has completed the journey, that he is free.”

The family members will return his remains to South Dakota for burial at Pine Ridge.

Cherokee Officials Ponder Raising Buffalo

By Meteor Blades

The Cherokee Nation wouldn’t be the first tribe to choose to raise buffalo for commercial purposes. The Intertribal Buffalo Council, a 21-year-old pan-Indian consortium of 56 tribes in 19 states, has a collective herd of 15,000, as reported in FNN&V earlier this year. Nationwide, there are about half a million buffalo in commercial herds. Estimates are that in 1800, there were 60 million of the animals, known also as bison, in North America.

Officials of the Cherokee Nation, the second largest Indian tribe in the United States (after the Navajo Nation), recently visited the buffalo ranch of Gerald Parsons in Stratford, Oklahoma, to learn if raising buffalo might make a good tribal enterprise. A veterinarian, Parsons has been raising buffalo since he bought his first animal in 1993 and now has about 100 head, with about 38 calves born each year.

Taking up buffalo ranching is not something done lightly. These aren’t cattle and there is much to learn. Fencing must be sturdier than that used to keep cattle penned. Buffalo can also be very aggressive. Parsons told Cherokee representatives that he feels good about raising an animal that survived the Ice Age extinctions and the (barely) the slaughters of the 1860s-1870s that were part of an attempt to tame the Plains tribes.

Parsons told them “The meat industry has just gone wild. You can’t raise enough of them. Right now we are so deficient in bison that the [meat] prices just keep going up.” Buffalo meat is leaner and healthier than beef. Parson said ranchers can graze three buffalo on the same land that would provide for two beef cows. “So it doesn’t take the space and grass like beef, yet they are going to produce you more income.”

The Cherokee, like all tribes, are eligible for a gift of 80 buffalo from the Yellowstone herd. Adult buffalo normally run about $3,500 per animal. In 1902, that Yellowstone herd of fewer than 50 animals was the only remnant of wild buffalo in the lower 48 states that had survived since prehistoric times. The herd now includes 4,200 genetically pure animals. Both the Montana reservations of Fort Peck (Assiniboine and Sioux) and Fort Belknap (Assiniboine and Gros Ventre) have small buffalo herds that include animals from the Yellowstone herd.

The Cherokee are still in the exploratory stages and have a lot of considering to do before taking on the project. It is not something done lightly, according to the tribe’s natural resources director, Pat Gwin. Although commercially the animals can be lucrative, sold for meat, hide and other parts, the tribe would probably have to expand the herd to 250 or more animals before the enterprise became commercially viable, Gwin said.

Obama Signs the HEARTH Act of 2012 to Promote Tribal Self-Determination

By navajo

(Official White House Photo by Pete Souza)

President Obama signed the Helping Expedite and Advance Responsible Tribal Home Ownership Act of 2012 on July 30. The HEARTH Act allows federally recognized tribes to lease restricted lands for business, agricultural, public, religious, educational, recreational or residential purposes without approval from the Secretary of the Interior. The measure received bipartisan support in both the House and Senate.

Senator John Barrasso (D-WY), the Vice Chairman of the Senate Indian Affairs Committee said: “Today, a bill to remove bureaucratic red tape and clear the way for Indian tribes to pursue homeownership and economic development opportunities on tribal trust lands became law. With record high unemployment rates, it’s crucial that we do everything we can to expand economic opportunities and job creation on tribal lands. This law will provide Indian tribes with tools to lease and develop their land faster and help increase the quality of life in Indian country.”

According to White House Senior Policy Advisor for Native American Affairs Jodi Gillette (Standing Rock Sioux):

The HEARTH Act builds on the Administration’s strong record of accomplishments for Native Americans and Native Alaskans and complements existing initiatives to strengthen tribal economies. Just recently, on July 12th, Treasury announced that it is opening up $1.8 billion of Tribal Economic Development (TED) bonds for reallocation to tribal governments. The TED bond program was established under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA), and provides tribes with the authority to issue tax-exempt debt for a wider range of activities to spur job creation and promote economic growth in Indian Country. By providing tribes with the ability to issue tax-exempt debt in a manner similar to that available to state and local governments, tribes can lower their borrowing costs and more easily engage in new economic development projects.

With the Cobell and Keepseagle Settlements, the Tribal Law and Order Act, water rights settlements, fee-to-trust reform, TED bonds, and now the HEARTH Act, this Administration’s accomplishments for Indian Country tell a very compelling story about how far we have gone to make meaningful progress on advancing tribal self-determination, promoting economic growth, and revitalizing our trust responsibility. Water and land are the primary trust assets we manage for Indian tribes, and the Obama Administration has made monumental strides by recognizing tribes as partners, ending the repetition of past mistakes, and working together to identify and develop concrete solutions that will improve the quality of life in tribal communities.

President Obama has shown stronger support for tribal self-determination than any President since Richard Nixon, and signing the HEARTH Act of 2012 was just another step in moving Indian Country forward.

-h/t to Land of Enchantment

Multimedia E-book ‘Little Crow’ Focus on Dakota War

By Meteor Blades

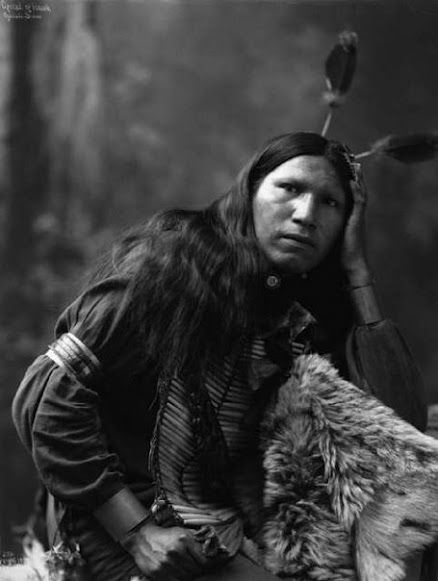

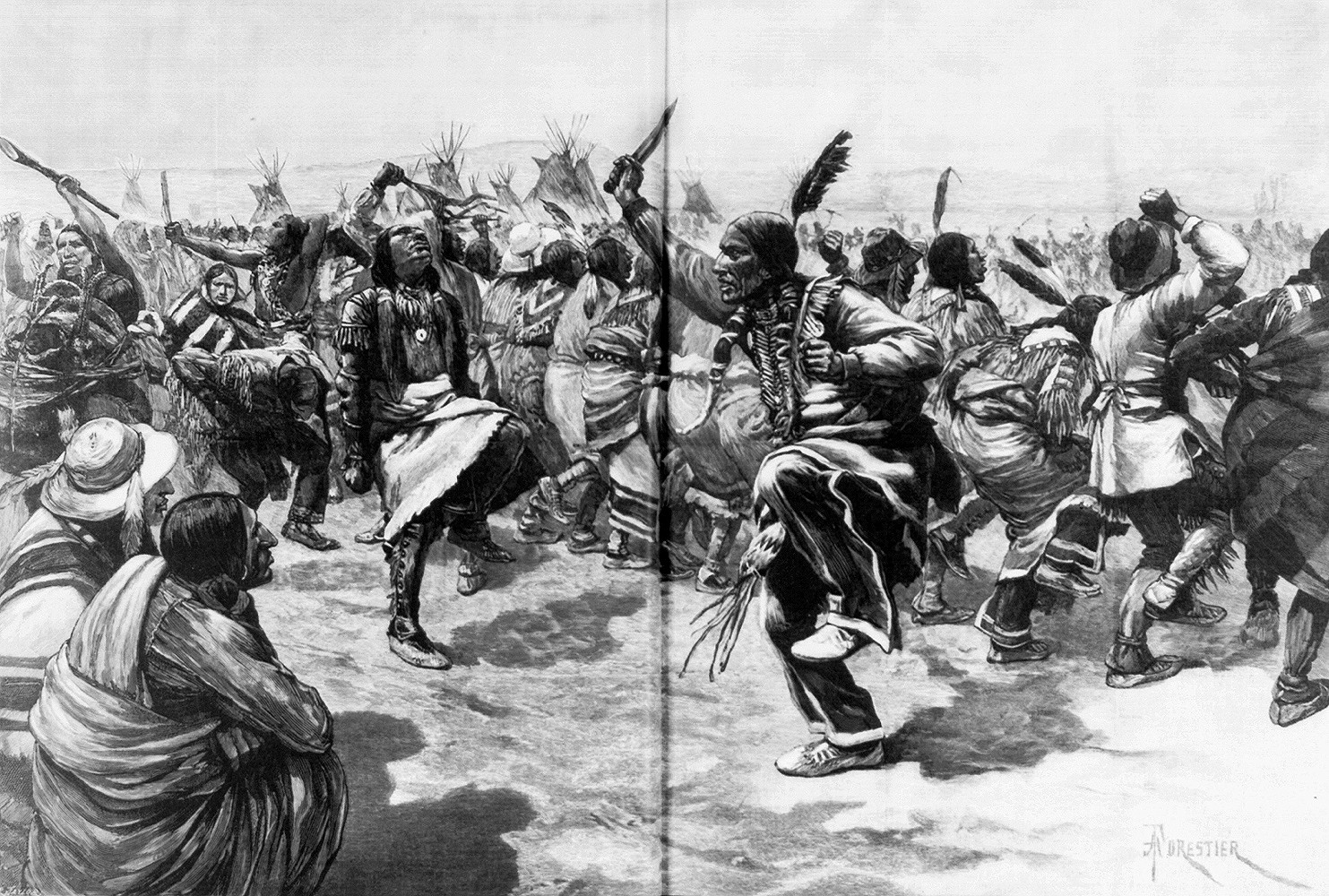

One hundred fifty years ago, as we have reported here and here, the brief but bloody Dakota War in Minnesota cost the lives of 600 whites and an unknown number of Dakota (Sioux). But the devastation to the various Dakota and Lakota people as a result of a U.S. policy of ethnic cleansing across the Plains, the Southwest and Northwest took a far greater toll over the next three decades, culminating in the massacre at Wounded Knee in December 1890.

The Dakota War began in that typical way almost all the Indian Wars from 1630 to 1890 did: a fight over land and broken promises of compensation for that land. It ended with the largest mass hanging in U.S. history, 38 Dakota men executed on the orders of Abraham Lincoln after 10 days of proceedings in a kangaroo military court.

That war and its aftermath is the subject of Curt Brown’s six-part e-book, In the Footsteps of Little Crow, the Dakota warrior who tried to avoid bloodshed until no other solution seemed possible. You can find a detailed summary of each part here and articles, like this one here from the Minneapolis Star Tribune. The e-book includes photos and video, including descendants of Little Crow reading from the text. Here’s an excerpt from Part 3, “When men become hungry, they help themselves”:

After the Dakota stormed the Upper Sioux Agency warehouse for food, Little Crow argued that the other warehouse at the Lower Sioux Agency should also be opened.

But citing protocol, Galbraith [Lincoln’s new Indian Agent] refused to do that until the gold money arrived. He didn’t want to have to organize the pay-table lineup and check the rolls twice.

Little Crow protested: “We have waited a long time. The money is ours but we cannot get it. We have no food but here these stores are filled with food.”

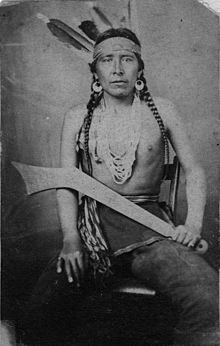

Jerome Big Eagle

Jerome Big Eagle(Mdewakanton Dakota)

He asked Galbraith to arrange for credit with the traders until the annuity payments arrived “or else we may take our own way to keep ourselves from starving. When men are hungry, they help themselves.”

Listening to Little Crow speak through a translator, Galbraith asked the shopkeepers what he should do. They shrugged and turned to store owner Andrew Myrick. Disgusted by the whole mess, Myrick walked away until Galbraith demanded a response.

“So far as I’m concerned, if they are hungry, let them eat grass or their own dung,” Myrick said.

Those words were, for the Dakota, the last straw. Myrick was later found dead with grass stuffed in his mouth.

Minnesota Gov. Mark Dayton released a statement on the anniversary of the start of the war:

I call for tomorrow, the 150th anniversary of August 17, 1862, to be “a Day of Remembrance and Reconciliation in Minnesota.” I ask everyone to remember that dark past; to recognize its continuing harm in the present; and to resolve that we will not let it poison the future.

You can listen to an interview by Cathy Wurzer of Minnesota Public Radio with Stanley Crooks, chairman of Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux (Dakota) Communityhere as he discusses the impact of the war today and the future of his people.

-h/t Nancy A. Heitzeg at Critical Mass

|

• Interior Dept. Opens Hearings on Protecting Sacred Sites: The Obama administration has begun an outreach program to American Indians seeking their ideas on doing a better job of protecting sacred sites. Interior wants to come up with a standard policy. Among the possibilities are mandatory consultation, new rules specific to certain sites or changes in legislation. The current situation has created numerous problems over the years. For example:

Representatives of the Quechan Tribe of the Fort Yuma Indian Reservation complained Monday about renewable energy projects on federal land being fast-tracked by the administration without adequate review of potential effects on sacred sites. […]

“These projects, they’re going on with complete disregard to Indians. It’s like we don’t have any say,” Bathke said, explaining that siting of the projects is more about spirituality than land planning for many tribes.

-Meteor Blades

• Minnesota Tribe Pays $1 Million a Year to its 460 Members: The reason the Shakopee Mdewakanton (Dakota) people are no longer living in beat-up trailers and living in poverty is the tribe’s casino and resort empire. As a result of divorce papers, secret pay-outs to members became known recently: $84,000 a month to each adult enrolled in the tribe. Unemployment on the reservation is the highest in the nation. Not because of lack of jobs, but because the income from the casinos means there is no need to work. Some tribal elders are worried that the money will corrupt tribespeople or make them lazy.

Most still live in modest homes on the reservation, albeit with luxury cars parked outside, but they often have second homes elsewhere, spend a lot of time traveling, send their children to private schools and take up expensive pastimes. Much the same as affluent people everywhere.

The tribe not only provides hundreds of jobs to local non-Indians, it also contributes large amounts to other tribes and to various charities, educational and medical institutes. In fact, the Shakopee have donated $243 million since 1996, a better record proportional to their income than many Fortune 500 companies that bring in billions in profits each year.

Not all Indian casinos are making big profits. And while Shakopee may not yet feel the heat, other reservation casinos have seen their business drop off sharply as the recession took its toll and legalized gambling run by non-Indians has received ever-wider approval. Some Indian casinos in remote areas barely break even and that margin will worsen as legal gambling spreads. For the tribes that have improved their economic circumstances, it’s a case of nice-while-it-lasted.

-Meteor Blades

• Blackfeet Conflicted Over Oil Drilling: The Blackfeet tribe of Montana is split over the leasing of a million of its reservation’s 1.5 million acres to oil companies. While everyone recognizes the benefits and potential benefits of the drilling-one rig generated 49 jobs for tribal members-there is also deep concern.

The oil is trapped in tight shale formations, which requires hydraulic fracking, a process that many environmentalists reject as potentially hazardous to underground water supplies. “These are our mountains,” said Cheryl Little Dog, a recently elected member of the Blackfeet Tribal Business Council, the reservation’s governing body. “I look at what we have, and I think, why ruin it over an oil rig?”

But the money, other Blackfeet say, is badly needed. So far, the tribe of 16,500 members has collected about $30 million from its lease agreements with oil companies. Some tribespeople argue that federal rules for getting reservation drilling permits signed are too cumbersome and should be loosened or done away with altogether. This cuts both ways. Indians have long had big problems with a federal bureaucracy that, depending on the era and the issue, controls, neglects, assists, protects or cheats them. But there is also a strong traditionalist current that often meshes with worries about environmental damage. Says tribeswoman Pauline Matt of the drilling, “It threatens everything we are as Blackfeet.”

-Meteor Blades

• Another Navajo Code Talker Walks On, Before National Day of Celebration

Navajo Code Talker, Reuben Curley, Sr., died at age 96 on Saturday, August 4, 2012, at his home in Flagstaff, Arizona. Curley was born on July 10, 1916, at Bird Springs, Arizona, to John and Nellie (Dixon) Nezzie. His Navajo paternal clan is Hashk’aanhadzohi’ (Yucca Fruit is Spread Out) and his maternal clan is Ashiihi (Salt). Curley had 40 grandchildren and 31 great-grandchildren.

He enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps in 1943 and served throughout World War II with the 2nd Marine Division, He was a qualified sharpshooter and fought in the battles of Tinian, Saipan, Guadalcanal and Okinawa. He later participated in the occupation of Japan. He was awarded a Purple Heart, plus various other medals.

He was one of a few selected to serve on a secret mission that used a code developed by speakers of Navajo and military cryptographers to transmit radio communications to Allied forces. A code within a code. The undecipherable cipher frustrated Japanese linguists who never cracked it. The Code Talkers are credited with saving thousands of lives during the war. They were always guarded by one or two other Marines so they would not be mistaken for a Japanese soldier. The Code Talkers are given considerable credit for the victory over Japan on Iwo Jima. Their mission remained a military secret and they returned home as silent heroes. Even though their story was finally told when the mission was declassified in 1968, Congressional Gold Medals were not awarded until 2001, 60 years after the war began. You can read more about Code Talker history here.

National Navajo Code Talkers Day (proclaimed in 1982) was celebrated August 14 at a celebration in Veteran’s Park in Window Rock, Arizona. Almost 20 Code Talkers attended. Navajo Nation President Ben Shelley spoke:

Ahe’hee’ for your service. Because of your service, my generation and those that followed have taken pride in who they are as Diné. […] Our Navajo Code Talkers have inspired an entire generation. For decades boarding schools tried to silence our native tongue. But when we learned our Diné language defeated the Japanese, we rejoiced in happiness because we now had heroes who were our own. Our language is sacred and used by heroes. […] Our language was given to us by the Holy People, and is supposed to be treated as sacred. Our words are expressions of our culture. We have passed our language down from generation to generation and it has sustained our way of life as Diné. […]

-navajo

• Shoshone-Bannock Elected President of USDA Native Farming Advisory Group: Mark Wadsworth (Shoshone-Bannock) was voted into the presidency of the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Council for Native American Farming and Ranching. The council was established by Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack as part of the Keepseagle settlement. Its role is to recommend ways to improve access by American Indian tribes to USDA programs and services, including financial credit. The Keepseagle settlement was agreed to as a means of dealing with the USDA’s long-standing discrimination against Indian farmers and ranchers.

-Meteor Blades

• Oglala Tribal Government Reopens Case of Pine Ridge Deaths: In the late winter of 1973, traditional Oglala Lakota people and members of the American Indian Movement (including Kossacks Carter Camp (cacamp), Madonna Thunder Hawk and me) occupied the village of Wounded Knee over grievances regarding the corruption of the tribal government and the failure of the federal government to fulfill its treaties.

It was the beginning of a siege, a tense, bullet-filled, 71-day stand-off with federal authorities. Once again, a piece of the Great Sioux Nation became ground zero in the bloody struggle between the government and the tribes. Two Indians were killed during the siege and an FBI agent died subsequently of wounds he had received.

But after the siege ended, the violence did not end. Local residents and AIM member Milo Yellowhair said: “There had been a tremendous amount of carnage on the reservation [and] it was almost a daily occurrence, when people were disappearing or died or were found dead. We always called it a ‘reign of terror.’”

Bad blood between the FBI and AIM has continued to this day, a product of the CoIntelPro operation that targeted African American, Indian and Latino activists with divisive actions, via agents provocateurs and disinformation, other heavy-handed tactics used by the bureau and its contract agents, and the slaying of two FBI agents on the reservation in 1975.

With the leading participants at Wounded Knee now in their 70s, the Oglala Tribal Council has called upon U.S. Attorney Brendan Johnson to look into 45 murders that occurred in the aftermath of the siege. Johnson may or may not turn out to be a good choice. He seems to have a pollyanna view of the FBI, according to reporting by National Public Radio. Both the FBI and AIM deny they had anything to do with the murders.

AIM members like 72-year-old Madonna Thunder Hawk welcome the U.S attorney’s review of these old cases, but doubts justice will be served.

“I mean come on, the U.S. government investigating itself, again … I’m skeptical,” Thunder Hawk says. “I’m glad it’s happening [and] I’m going to sit here and watch.”

She isn’t alone in her skepticism.

-Meteor Blades

• Choice of Paul Ryan Doesn’t Resonate with Indians: Mitt Romney has selected a vice presidential candidate who is no friend of American Indians. Among other things, he has voted against the Cobell settlement, the Indian Health Care Improvement Act as part of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act and the ground-breaking Tribal Law and Order Act. Most of his other votes have included Indian matters as part of broader legislation, so it is difficult to determine how he might have voted if these had been standalone laws. He did, however, vote for the GOP version of the renewal of the Violence Against Women Act that specifically excluded changes making it easer for Indian women to seek protection from non-Indian abusers living on reservations. Currently, tribal courts have no jurisdiction in cases of domestic violence involving a non-Indian attacking an Indian and regular courts rarely see such cases because prosecutors aren’t interested.

-Meteor Blades

• Cherokees Limit Top Posts to Citizens of the Tribe: In a move Principal Chief Bill John Baker and Tribal Attorney General Todd Hembree called unconstitutional, the Cherokee Nation Tribal Council has voted 9-8 to limit five top executive posts to enrolled members of the Cherokee Nation. Under tribal rules, the only people who can be enrolled are those who can trace their ancestry to the Dawes Rolls, a federal registry of the Cherokee, Choctaw, Creek, Chickasaw and (Oklahoma-based) Seminole people. Even someone who is 1/64th Cherokee by blood can be a member if s/he has an ancestor on the rolls, which are notorious for having done things like categorizing one sibling as Indian and another as not although they were offspring of the same parents.

-Meteor Blades

Indians have often been referred to as the “Vanishing Americans.” But we are still here, entangled each in his or her unique way with modern America, blended into the dominant culture or not, full-blood or not, on the reservation or not, and living lives much like the lives of other Americans, but with differences related to our history on this continent, our diverse cultures and religions, and our special legal status. To most other Americans, we are invisible, or only perceived in the most stereotyped fashion.First Nations News & Views is designed to provide a window into our world, each Sunday reporting on a small number of stories, both the good and the not-so-good, and providing a reminder of where we came from, what we are doing now and what matters to us. We wish to make it clear that neither navajo nor I make any claim whatsoever to speak for anyone other than ourselves, as individuals, not for the Navajo people or the Seminole people, the tribes in which we are enrolled as members, nor, of course, the people of any other tribes.

Leave a Reply