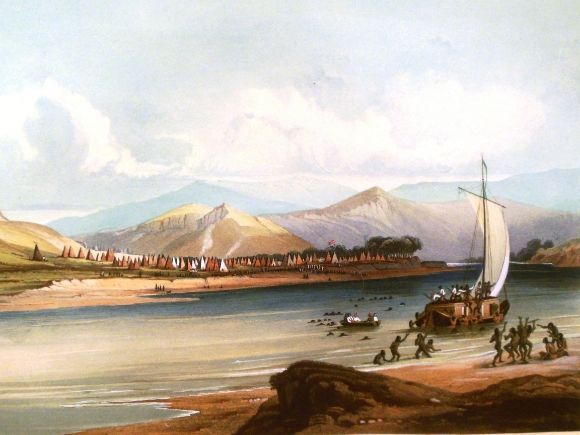

During the nineteenth century the concept of the museum-its form, structure, and purpose-evolved. Museums began as simply cabinets of curiosities which were often glass-fronted cabinets in which a collection of unusual “stuff” was displayed. There might be a fossil next to an ancient stone implement next to a stuffed animal. These cabinets of curiosities were often found in the homes of wealthy individuals, in government offices, and in prominent businesses. Commonly included were American Indian artifacts, both ancient and modern.

During the first part of the nineteenth century, museums simply put American Indian artifacts in their cabinets of curiosities without any attempt to explain Indian cultures. Sometimes the artifacts might be labeled by tribe or geographic location, but for the most part the displays simply held the artifacts for the curious public to observe. By the middle of the nineteenth century, however, museum curators were more concerned with arranging or grouping Indian artifacts so that they told a story. To do this, many curators used one or more of three basic interpretive models: Biblical, Racial, and Evolutionary.

Biblical:

When the Europeans first arrived in the Americas, they encountered peoples and civilizations which had not been mentioned in their creation story as written in the Bible. With an ethnocentric arrogance, the Europeans assumed that their creation story was not only universal, but the only “real” creation story. Thus all interpretations of American Indians and their histories had to be made through a Biblical lens.

As museum curators began to arrange American Indian artifacts in their cabinets of curiosities during the nineteenth century, there were some who felt that these artifacts should tell a Biblically-based story. Thus, with regard to chronology, artifacts were sometimes labeled as antediluvian or post-diluvium in reference to the Christian myth of a flood. Similarly, Indians were viewed as “lost tribes of Israel” or somehow related to either the Jews or to some other Biblical people from southwest Asia.

Racial:

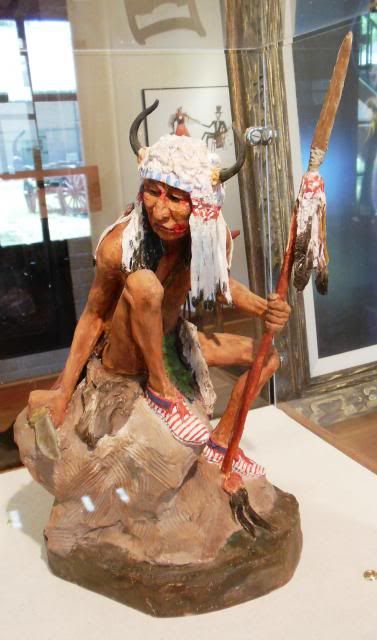

During the nineteenth century many Americans, including scientists, politicians, educators, philosophers, popular writers, journalists, and museum curators began to view the differences seen among the different peoples of the world as stemming from a pseudo-scientific concept of race. The way people behaved, they strongly believed, was inherited. Thus, human behavior was seen as being based in blood (which led to the use of blood-quantum as a way of determining who is Indian and who is not), skull shape and size, and skin color (Indians were assigned to a race called “red” and Europeans to a race called “white.”) Following this model, some museums arranged their displays to focus on race, with the clear understanding that the “white” race was somehow superior to all others.

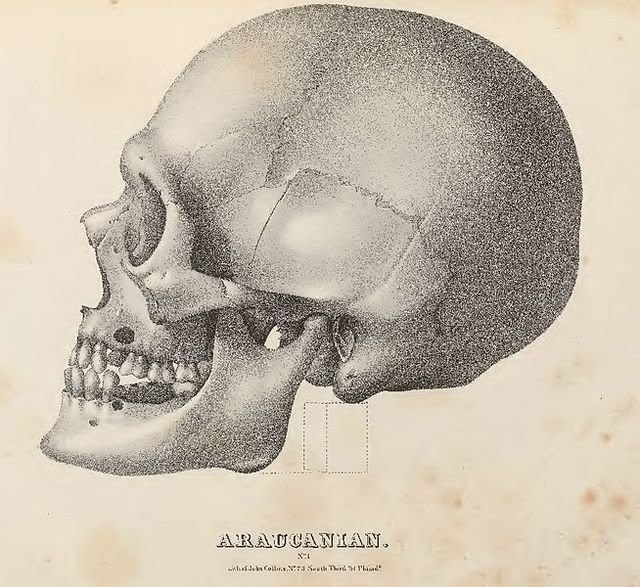

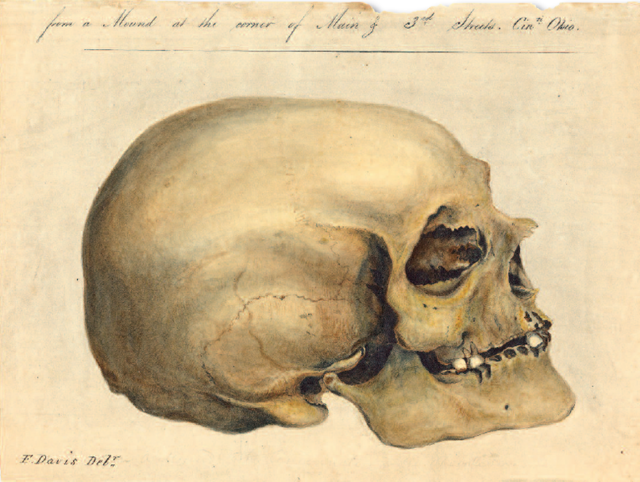

One prominent example of this type of racial analysis can be seen in 1839 when physician Samuel George Morton, in Crania Americana, summarized his measurement of hundreds of human skulls. He demonstrated that “caucasians” had big brains (an average of 87 cubic inches) and that Indians had smaller brains (an average of 82 cubic inches). Based on this data, many scientists viewed “caucasians” as having superior intellectual capability. He describes Native Americans this way:

“The American Race is marked by a brown complexion; long, black, lank hair; and deficient beard. The eyes are black and deep set, the brow low, the cheekbones high, the nose large and aquiline, the mouth large, and the lips tumid [swollen] and compressed. In their mental character the Americans are averse to cultivation, and slow in acquiring knowledge; restless, revengeful, and fond of war, and wholly destitute of maritime adventure. They are crafty, sensual, ungrateful, obstinate and unfeeling, and much of their affection for their children may be traced to purely selfish motives. They devour the most disgusting [foods] uncooked and uncleaned, and seem to have no idea beyond providing for the present moment. … Their mental faculties, from infancy to old age, present a continued childhood. … [Indians] are not only averse to the restraints of education, but for the most part are incapable of a continued process of reasoning on abstract subjects.”

Morton’s assumption that brain size is directly related to intellect is later proven to be false. In addition, later studies could find no differences in the average skull sizes of people from Europe and those of American Indians. It appears that Morton deliberately biased his data by selectively reporting the data, and manipulating the sample compositions. In this way, he got the data to support his predetermined conclusions.

Morton is shown above.

Shown above are illustrations from Crania Americana.

Inspired by Morton’s work, Army personnel in 1868 were ordered by the Army Surgeon General to obtain as many Indian skulls as possible for the Army Medical Museum. Under this order, over 4,000 Indian heads were taken from corpses at battle grounds, prisoner of war camps, hospitals, and Indian graves. Any grave goods found with the skulls are donated to the Smithsonian Institution. The assistant surgeon general explained the reason for collecting skulls:

“The chief purpose had in view in forming this collection is to aid the progress of anthropological science by obtaining measurements of a large number of skulls of aboriginal races of North America.”

Eventually, the skulls acquired through this type of collection wound up in the Smithsonian.

Evolutionary:

As scientists during the nineteenth century began to understand the concept of biological evolution, there were some social scientists who began to explain human behavior in terms of cultural evolution. Under their hierarchical model, contemporary American society represented the pinnacle of social evolution and all other societies were not only inferior but were destined to evolve or go extinct.

The concept of cultural evolution was developed by Lewis Henry Morgan who had earlier worked among the Seneca. In 1877 Morgan published Ancient Society: or Researches in the Lines of Human Progress from Savagery Through Barbarism to Civilization in which he identified various stages of cultural evolution: Savagery (Lower, Middle, Upper), Barbarism (Lower, Middle, Upper), and finally Civilization. In particular, he put forth the idea that Civilization required the monogamous nuclear family and private property. Under this scheme, Indians were placed in either Upper Savagery or Lower Barbarism, depending on their material and political development. Morgan’s concepts were used in the formulation of Indian policies designed to “lift” Indians from “savagery” and “barbarism” to “civilization.”

Lewis Henry Morgan is shown above.

Leave a Reply