Who Owns the Land?

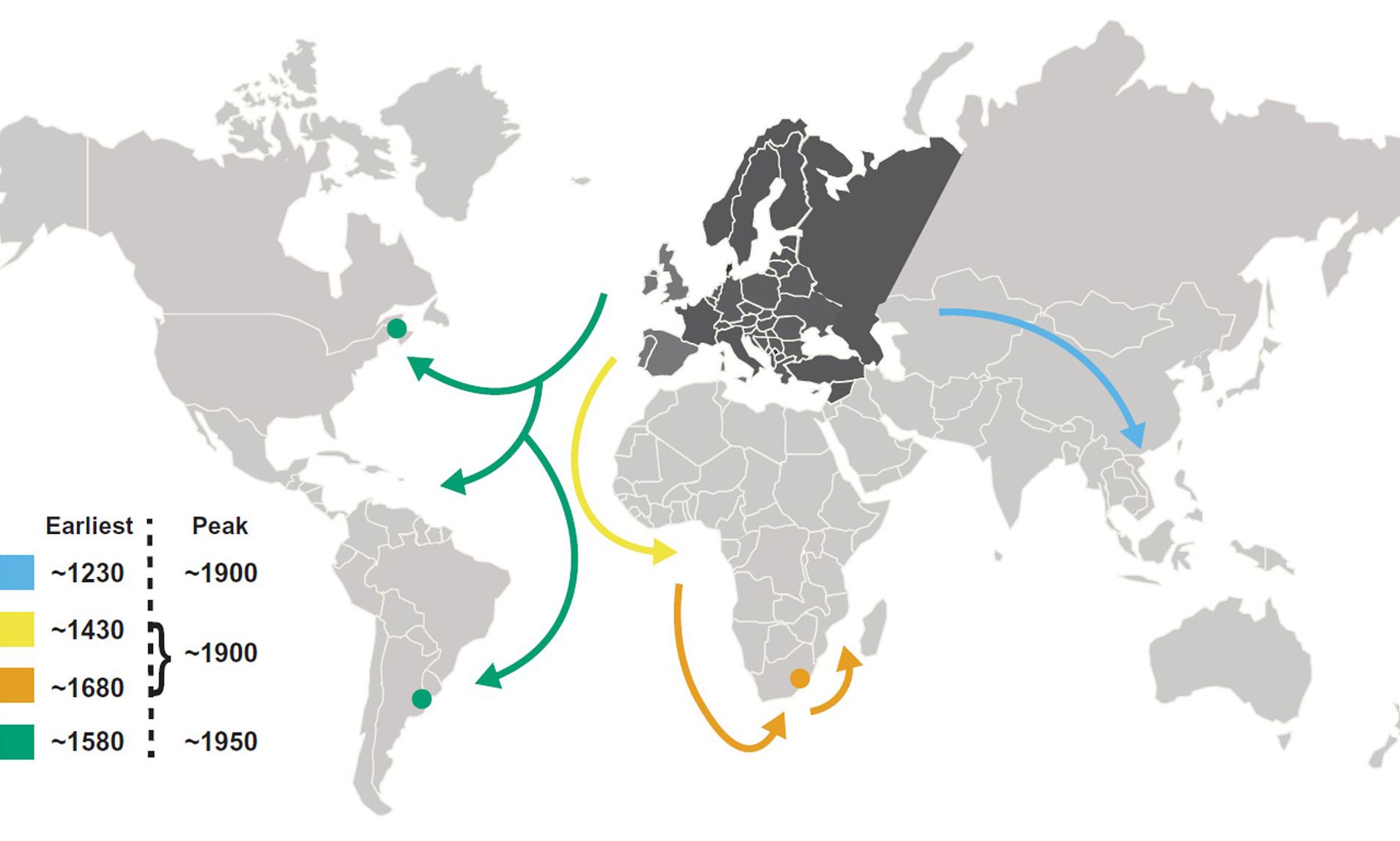

When the Europeans first blundered into the Americas, they found a land that was already occupied and developed. In 1532, Spanish judge Francisco de Vitoria declared that non-Christians could own property and therefore Indians may have title to their land. After the creation of the United States at the end of the eighteenth century, the issue of the ownership of Indian lands continued to be debated in the court system.

Background:

The English adopted the concept of vacuum domicilium which meant that if they felt that the lands were “vacant”—lacking land development (meaning fenced fields) and permanent structures (meaning English-style buildings)—then they could be occupied and possessed without any concern for actual Indian ownership or use of the land. From the English viewpoint, only land that is tilled, fenced, and built upon was owned.

In listing the legal fictions that form the basis of American law regarding American Indians, attorney Walter Echo-Hawk, in his book In the Courts of the Conqueror: The 10 Worst Indian Law Cases Ever Decided, includes these:

Native land is wasteland or a savage wilderness that no one owns, uses, or wants and is available for the taking by colonists—therefore any aboriginal interests in the land are extinguished as soon as British subjects settle the area.

Native peoples have no concept of property, do not claim any property rights, or are incapable of owning land.

Christians have a right to take land from non-Christians because heathens lack property rights.

There is an assumption that the European use of the land had a higher value than Native use. Anthropologist Samuel Wilson, in his book The Emperor’s Giraffe and Other Stories of Cultures in Contact, reports:

“The idea that Europeans might put the land to higher use required downplaying how the native people were using it.”

Since the Natives were already farming the land, particularly the best land, this meant that the English had to construct stereotypes of the Indians which portrayed them as nomadic hunters who did not modify or improve the land.

One of the common misconceptions is that Indian nations had no concept of land ownership at this time. Law professor Rebecca Tsosie, in her chapter in American Indian Nations: Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow, writes:

“While it is true that no Native people employed the concept of ‘fee simple’ or maintained written land titles prior to the arrival of the Europeans, there is a rich tradition of ‘rights’ and ‘responsibilities’ that accompanies Native narratives about the land. In the broader sense of ‘ownership,’ Native peoples most definitely maintained political and cultural claims to their ancestral lands.”

Preparing the Lawsuit:

In 1763, the British Crown had issued a decree which prohibited non-Indian settlement west of the Appalachians. Ignoring this decree, many Americans, including George Washington, had speculated in land in the western region. While British law held that these land purchases were illegal, after the formation of the United States questions about legal titles were clouded. Did Indians and/or Indian nations have the right to sell their land to speculators, or did the United States now own this land and Indians simply held an occupancy right?

Attorney Robert Goodloe Harper set out to clarify the land speculators’ title through the court system. To do this he contrived a controversy which he could bring to the Supreme Court. Walter Echo-Hawk reports:

“First, he selected all of the players in the lawsuit—not only the plaintiff, who Harper would represent, but he also hand-picked the defendant and hired the defendant’s attorneys who were paid by the land companies and told what to do throughout the litigation.”

Thomas Johnson was selected as plaintiff because of his close ties to people admired by Supreme Court Chief Justice Marshall. The defendant—called “pretend defendant” by Walter Echo-Hawk—was William McIntosh (M’Intosh). Walter Echo-Hawk writes:

“M’Intosh was picked because of his willingness to collude and play ball with the law.”

With regard to arguing the case before the Supreme Court, Walter Echo-Hawk writes:

“Harper selected the great Daniel Webster—the most eloquent and powerful orator of the day—as his co-counsel to assist in arguing the case on behalf of Johnson, and then he picked less-qualified attorneys to argue M’Intosh’s case, paid them, and told them what to say.”

The Lawsuit:

Before the Supreme Court, Harper and his team argued that any British prohibition of land sales had been invalid as the Indian tribes owned the land. McIntosh’s attorneys, coached by Harper, argued only that land sales had been barred by British law.

While this case involved American Indians and its outcome would impact the lives of Indian people for the next two centuries, there were no Indians in the courtroom and it is doubtful that any Indians even knew it was being argued. Harper described Indians as “savage tribes” and the attorneys for McIntosh saw them as “an inferior race of people, without the privileges of citizens.”

Walter Echo-Hawk writes:

“Everyone’s use of racial invectives in Johnson leaves us to ponder the Court’s ability to render an impartial decision concerning Indian land rights. The avowed racist views expressed by the Court and the parties assured that those rights would not be represented.”

In the 1823 decision Johnson and Graham’s Lessee versus McIntosh the Supreme Court declared that the United States has the power to extinguish the Indian right of occupancy and that absolute ultimate ownership of the land lies with the United States. The case involved valid title to the land: Johnson claimed that title comes from the Piankshaw while McIntosh claimed that title comes from the federal government. In his book Conquest by Law: How the Discovery of America Dispossessed Indigenous Peoples of Their Lands, law professor Lindsay Robertson reports:

“The indigenous owners were converted into tenants on their lands and denied the right to sell their ‘leases’ on the open market.”

Law professor Bruce Duthu, in his book American Indians and the Law, writes:

“The case required a ruling on the nature of Indian property interests to determine which of the non-Indian parties held superior title to the lands in dispute.”

The Court found that the Discovery Doctrine gave sovereignty to England and then to the United States. Indian tribes, under this Doctrine, have a right of occupancy to the land. Christian nations, such as England and the United States, have superior rights over the inferior culture and inferior religion of the Indians. In reviewing the long history of land claims, Chief Justice John Marshall wrote:

“It has never been contended that the Indian title amounted to nothing. Their right of possession has never been questioned.”

According to the Court:

“The tribes of Indians inhabiting this country were fierce savages, whose occupation was war, and whose subsistence was drawn chiefly from the forest. To leave them in possession of their country, was to leave the country a wilderness.”

Indians, found the Court, had been compensated for their lands by having Christianity and civilization bestowed upon them.

With regard to the sovereignty of Indian nations, the Court declared:

“They were admitted to be the rightful occupants of the soil, with a legal as well as just claim to retain possession of it, and to use it according to their own discretion; but their rights to complete sovereignty, as independent nations, were necessarily diminished, and their power to dispose of the soil at their own will, to whomsoever they pleased, was denied by the original fundamental principle, that discovery gave exclusive title to those who made it.”

In their book Tribes, Treaties, and Constitutional Tribulations, legal historians Vine Deloria and David Wilkins summarize McIntosh this way:

“the culture and religions of indigenous peoples was judged inferior to that of Europeans, civilization and Christianity were offered them as compensation for their lands, discovery gave title to a government against other Europeans, the Indians were still the rightful owners of the land, but their sovereignty was reduced by the European agreement to restrict the sale of land to the discovering country.”

Steven Newcomb, Director of the Indigenous Law Institute, in a column in Indian Country Today, writes of the legal doctrine expressed in McIntosh:

“Based on this bizarre theory, our very existence as Indians is now assumed to be subordinate to, ruled by, and possessed as property by, the political and legal successor of the first Christian ‘discoverers,’ namely, the United States.”

Newcomb also writes:

“From the perspective of Western Christendom, it was the ‘god-given’ right of all Christian sovereigns to locate and dominate (“possess”) all non-Christian lands on the planet.”

Richard West and Kevin Gover, in an article in The Impact of Indian History on the Teaching of United States History, see Justice Marshall’s decision as practical:

“The title of every landowner in the country would have been clouded had the Court failed to acknowledge the discovery doctrine.”

With regard to the importance of McIntosh, attorney Glenn Morris, in a column in Indian Country Today, writes:

“Johnson v. M’Intosh is the opinion upon which the entirety of federal Indian law (and U.S. property law) is constructed. Every destructive opinion by the Supreme Court, every destructive policy of Congress or the president to this day, is made possible because of Johnson v. M’Intosh.”

With regard to Chief Justice John Marshall’s opinion, Walter Echo-Hawk writes:

“The bulk of his opinion went on to strip the legal title to land away from American Indian tribes in North America and to justify what amounted to judicial theft of Indian land.”