The Smithsonian and the Indians in the 19th Century

In 1846, Congress created the Smithsonian Institution to fulfill the terms of the will of James Smithson. The Smithsonian was given custody of all federal government museum collections, including collections of Indian artifacts. The Smithsonian’s regents encouraged the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to collect items which would illustrate the history, manners, and customs of the Indians.

The Smithsonian “Castle” is shown above.

In a lecture at the inaugural meeting of the Smithsonian Board of Regents, Henry Rowe Schoolcraft pointed out that it was the task of museums to preserve the full array of artifacts produced by each Indian nation before these nations disappeared. He told the Regents:

“It is essential to the purposes of comparison, that a full and complete collection of antiquarian objects, and the characteristic fabric of nations, existing and ancient, should be formed and deposited in the Institution.”

The law creating the Smithsonian also stated that

“all collections of rocks, minerals, soils, fossils, and objects of natural history, archaeology and ethnology [made by or for the government], when no longer needed for investigations in progress shall be deposited in the National Museum.”

The Smithsonian Institution opened its first exhibits building in 1858. Only one of the fifteen display cases contained Native American materials.

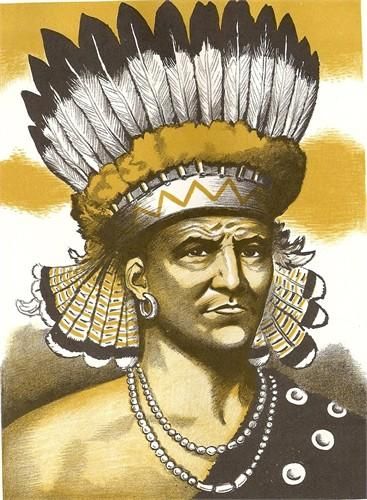

In 1865, the National Indian Portrait Gallery was established as a part of the Smithsonian Institution. The key elements of the Gallery were the portraits of Indian chiefs who visited Washington, done by Charles Bird King for the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

Obtaining Indian Materials:

During the nineteenth century, the Smithsonian began to obtain what would become its vast holdings of American Indian artifacts through: (1) gifts from wealthy individual collectors, (2) direct purchase from Indians and from looters, (3) consolidation with collections from other governmental agencies, and (4) theft. Some of the materials obtained by the Smithsonian were ancient– artifacts dug up by archaeologists and by looters, while others were contemporary, articles made by Indian artists and craftspeople.

In Virginia, the Pamunkey were still making their traditional pottery in 1878. Some of this pottery was purchased for display in the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. One professor described the Pamunkey as

“a miserable half-breed remnant of the once powerful Virginia tribes. The most interesting feature of their present condition is the preservation of their ancient modes of making pottery.”

In 1880, anthropologist Frank Hamilton Cushing observed the beginning of a religious pilgrimage by Zuni priests to Kolhu/wala:wa (Zuni Heaven) In New Mexico. Later in the year, Cushing sneaked out of the village and followed the ancient trail to Kolhu/wala:wa where he looted the shrines, packing the prayer sticks and offerings to be shipped to the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C. The theft was discovered by the Zuni who tried Cushing in a religious court. As news of Cushing’s “discovery” spread, other non-Indians looted the shrines at Kolhu/wala:wa.

The Bureau of Ethnology sent an expedition to the Hopi pueblos in 1882 to survey the villages and to make a collection of material goods. They were instructed to “clean out” Oraibi, one of the oldest continuously inhabited villages in North America, but were threatened by the elders when the purpose of the trip became known. Still, they managed to obtain more than 200 specimens at Oraibi and 1,200 from the three villages of Second Mesa.

When the Hopi materials arrived in Washington, the Smithsonian did not have room for them. Much of the material was simply left outside until space could be found for it. Material damaged from being exposed to the elements was simply discarded as the museum staff was overwhelmed by the pace of collecting and could not keep up with it.

Exhibitions:

During the nineteenth century, the Smithsonian exhibited some of its materials outside of Washington, D.C. In 1876, the Smithsonian participated in the Philadelphia Centennial International Exhibition, The Exhibition’s primary purpose was to emphasize America’s industrial and agricultural prowess. The Smithsonian Institution created American Indian exhibits that portrayed Indians as primitive or savage counterparts to the civilized Americans.

In Philadelphia, the Smithsonian also exhibited a portion of its collection of Northwest Coast Indian artifacts and art work. The exhibit elicited intensely negative comments from the public. The Indian, as shown in the exhibit, according to Atlantic Monthly editor William Dean Howells,

“is a hideous demon, whose malign traits can hardly inspire any emotions softer than abhorrence.”

Publications and Education:

In addition to displaying American Indian artifacts, the Smithsonian Institution also began to publish information about American Indians based on archaeology and on ethnography.

One of the controversies during the nineteenth century centered on the “mounds” and who had built them. Many prominent Americans, both politicians and scholars, strongly believed that these great features could not have been built by “primitive” Indians and must be evidence of an earlier, more advanced, civilization which built the mounds and then moved elsewhere. There were, however, some, such as Thomas Jefferson, who argued that Indians had indeed constructed these great works.

The large earthen pyramid known as Monks Mound in Cahokia, Illinois is shown above.

The Smithsonian Institution published Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley by Ephraim Squier and Edwin Davis in 1849. This book provided a record of the mounds as they appeared in 1847. It contained finely executed maps and detailed measurements. While Squire and Davis explicitly set out to avoid speculations and simply provide a detailed description of these features, they still suggested that the mounds had been constructed by a “civilized”, pre-Indian culture which had migrated southward under “incessant attack” by “hostile savage hordes.”

Shown above are illustrations from their book.

Many of the earthworks which described by Squire and Davis have been destroyed by urbanization and other forms of American progress and today’s archaeologists find their detailed descriptions to be valuable.

The Smithsonian helped to settle the debate about who built the mounds with the publication of The Problem of the Ohio Mounds by Cyrus Thomas in 1889. In the beginning of the book, Thomas writes:

“The opinion advanced in this paper, in support of which evidence will be presented, is that the ancient works of the State are due to Indians of several different tribes, and that some at least of the typical works, were built by ancestors of the modern Cherokees.”

Using evidence derived from excavations of the mounds rather than historical European texts, Thomas goes on to build his case using scientific reasoning rather than religious and/or political philosophy.

The Smithsonian also published descriptions of existing Indian cultures. Assuming that these cultures were vanishing before the superior American civilization, these efforts are sometimes described as salvage ethnography. In 1856, for example, the Smithsonian published Sketch of the Navajo Tribe of Indians, Territory of New Mexico by Dr. Jonathan Letherman. He reported:

“Of their religion little or nothing is known, as, indeed, all inquiries tend to show that they have none” and “They have frequent gatherings for dancing.”

Ethnology:

In 1879, Congress created the Bureau of Ethnology (later the Bureau of American Ethnology) as a part the Smithsonian Institution. The Bureau was responsible for a variety of different surveys of American Indians. The Bureau was to increase and diffuse knowledge of American Indians. Within the Smithsonian, the Bureau was viewed as a kind of unwanted but tolerated stepchild.

Major John Wesley Powell was the first director of the Bureau of Ethnology. Like his mentor Lewis Henry Morgan, Powell strongly believed that all cultures had to pass through a series of stages, commonly labeled as Savagery (foraging), Barbarism (farming land in common), Civilization (individualized farming), and Enlightenment (industrialization).

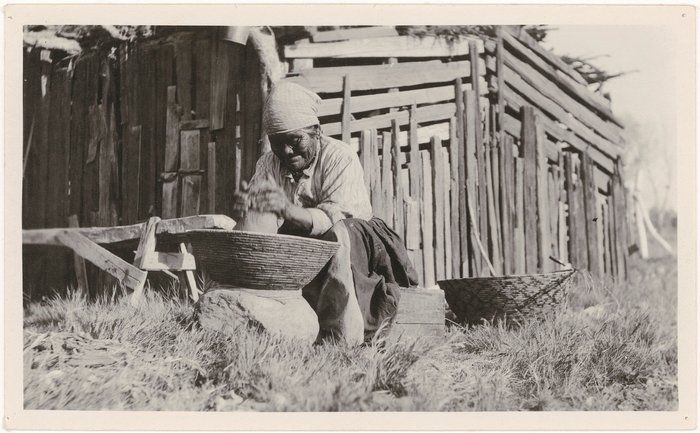

Shown above is Powell working among the Paiute in the Grand Canyon area.