The United States bought Alaska from the Russians in 1867. The Russians had never attempted to force the Alaska natives to recognize Russian ownership, nor had they made any treaties with the natives, nor had they purchased any land from the natives. The Russians had never had any effective control over the natives and the total Russian population in Alaska was less than 800, living in four very heavily fortified towns. In the transaction, the natives were barely mentioned and there was more concern for the protection of those Russians who might want to remain.

The Tlingit watched the ceremonial transfer from Russia to the United States at New Archangel (present-day Sitka) with great interest. Since Indians were not allowed in town, the Tlingit watched from their canoes in the harbor.

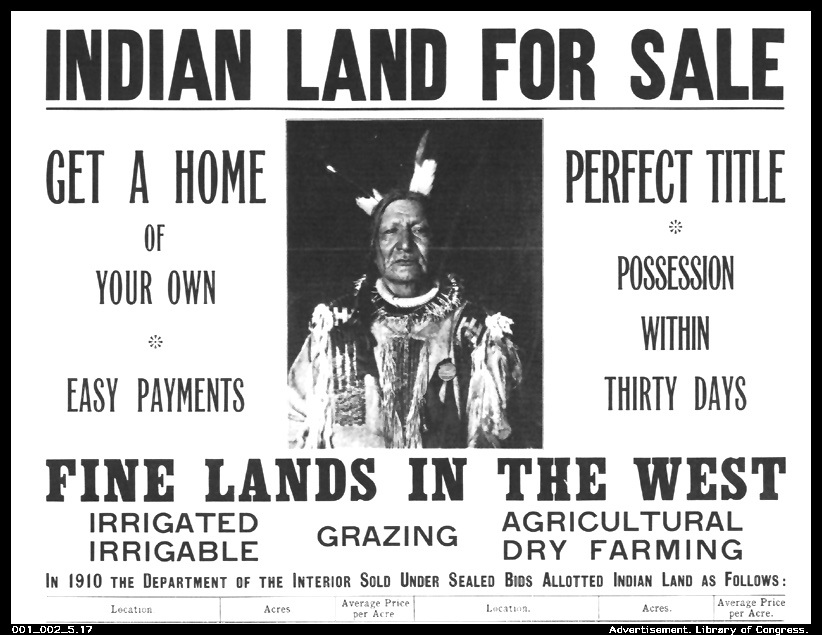

Under an international law known as the Discovery Doctrine, the Indian nations of Alaska had no say in this transfer. The Discovery Doctrine, which currently forms the basis of American Indian law, says that Christian nations, such as the United States, have a right to govern all non-Christian nations. Thus, the United States ignored not only the sovereignty of Indian nations, but also the rights of these nations to access the resources on the lands and seas which they had traditionally used.

At the time the United States took over Alaska there were an estimated 31,000 Natives in the territory and about 300 non-Indians, most of whom lived in what would become Sitka. The Americans were more concerned with the rights of the non-Indians than with those of the Indians.

In 1884, Congress passed the Alaska Organic Act which specified that native use of the land would not be disturbed, but it did not give them title to the land. It was the feeling of Congress that this Act was needed for the development of Alaska’s extensive resources, including mineral rights and timber.

Following World War II, the United States entered into a period in which a great deal of timber was needed to provide the lumber for the houses which were being built. To provide timber for the housing boom, the United States Department of Agriculture authorized timber harvest on the Tongass National Forest in Alaska. There was neither concern nor acknowledgement that the timber which was harvested was on lands which were traditionally claimed by the Tee-Hit-Ton, a subgroup of the Tlingit.

The Tee-Hit-Ton brought action in the Court of Claims for compensation under the Fifth Amendment for timber taken from tribal lands. The tribe argued that it had full proprietary ownership of the timber. The federal government, on the other hand, asserted that if the Tee-Hit-Ton had any rights at all, they were to use the land at the government’s will.

The Court of Claims found that the Tee-Hit-Ton were an identifiable group residing in Alaska and that its interests in lands prior to the purchase of Alaska by the United States were “original Indian title.” Since Congress didn’t recognize the tribe’s legal rights regarding property ownership, the Court dismissed the case.

In 1954, the United States Supreme Court heard arguments in the Tee-Hit-Ton case. The government argued that under international law Christian nations can acquire lands occupied by heathens and infidels. It was an argument made by the United States government on the basis of the Christian religion. In their argument, the United States government not only cited the nineteenth century case of Johnson v M’Intosh, but also the Papal bulls of the fifteenth century and the Old Testament from the Bible.

In 1955, the Supreme Court announced its decision which denied the Tee-Hit-Ton any compensation for the taking of the timber. According to the Court:

“The Christian nations of Europe acquired jurisdiction over newly discovered lands by virtue of grants from the Popes, who claimed the power to grant Christian monarchs the right to acquire territory in the possession of heathens and infidels.”

The Supreme Court denied compensation and asserted:

“No case in this Court has ever held that taking of Indian title or use by Congress required compensation.”

In order to be compensated under the Fifth Amendment, the tribe would have needed some prior acknowledgement of land ownership through a treaty, a statute, or an executive order. The Alaska Organic Act did not recognize aboriginal land ownership.

In its finding, the Court views the Indians as nomads who have not developed the land:

“The Tee-Hit-Tom were in a hunting and fishing stage of civilization, with shelters fitted to their environment, and claims to rights to use identified territory for these activities as well as the gathering of wild products of the earth.”

The Tee-Hit-Ton case reaffirmed the Discovery Doctrine as the basis for U.S. law with regard to Indian nations. It reaffirmed this Christian doctrine as the principle to be used in judging American Indians and discounted American Indian history and religious traditions. While denying that Indians have any legal rights as pagan nations, the Court also stated:

The American people have compassion for the descendants of those Indians who were deprived of their homes and hunting grounds by the drive of civilization. They seek to have the Indians share the benefits of our society as citizens of this Nation. Generous provision has been willingly made to allow tribes to recover for wrongs, as a matter of grace, not because of legal liability.

Leave a Reply