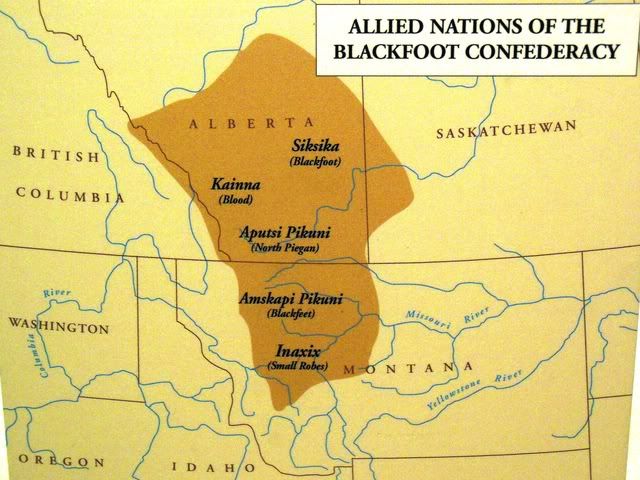

The Blackfoot were the most feared Indian nation on the Northern Plains in the nineteenth century. The United States established their reservation in 1851 at a treaty council held in Fort Laramie, Wyoming. Since no Blackfoot chiefs were in attendance, the government probably felt safe in declaring all of the land north of the Missouri River as their reservation.

The Blackfoot signed their first treaty with the United States in 1855, when they met with Territorial Governor Isaac Stevens and others at the Judith River. The Treaty of Judith River establishes the Great Blackfeet Reservation which includes 17.5 million acres north of the Missouri River and east of the Rocky Mountains. Governor Stevens told the Blackfoot:

“This country is your home. It will remain your home.”

Meeting in the council were not only the various Blackfoot tribes (Piegan and Blood), but also the Flathead, Nez Perce, Gros Ventre, Kootenai, Pend d’Oreille, Cree, and Shoshone. One of the primary Blackfoot concerns was hunting rights. They feared that being restricted to the reservation would restrict them from their traditional hunting grounds. On the other hand, the other tribes did not want to see the Blackfoot granted exclusive hunting rights to contested areas. In the end, the western Indians were given the right to hunt from the Mussleshell River to the Yellowstone River.

The treaty promised to provide the Blackfoot with annuities, to provide them with instruction in agricultural pursuits, to educate their children, and to promote civilization and Christianization. Indian treaty violations were to result in deductions from the annuities. This assumed that only the Blackfoot would violate the treaty. There was no penalty for non-Indians, including the federal government, if they were to violate it.

Fort Benton was designated as the Indian Agency for the Blackfoot. The Indian Agent’s duties were to distribute annuities to the tribes of the Blackfoot Confederacy and to maintain peace between the Indians and non-Indians in the region.

By 1865, non-Indian settlement in Montana was increasing and these new settlers felt that they were somehow entitled to Indian land. Therefore, the United States met with the Blackfoot and the Gros Ventre to convince them to move their southern boundary in order to allow American settlers to move in.

Many U.S. and Indian dignitaries assembled at Fort Benton for the Treaty Council. The Indian agent for the Blackfoot is described by his contemporaries as knowing as much about Indians as he did about the inhabitants of the planet Jupiter.

As all were assembling just outside of the fort, someone decided that the chiefs who had gathered for the treaty council should be shown American military might. A freight train which had been passing through included a mule which was carrying a cannon barrel strapped to its back. Some non-Indian of questionable intelligence decided that it would be a good idea to set off the cannon while it was still being carried by the mule.

The cannon was carried so that the muzzle pointed toward the mule’s tail. The gathered non-Indians, intent on impressing the Indians with their might and intellectual superiority, filled the cannon with powder and grape shot. A fuse was inserted and lit. The mule, hearing the fizzle of the fuse, turned to look. The River Press reported:

“As his head turned, so his body turned and the howitzer began to take in other points of the compass. The mule became more excited as his curiosity became more and more intense. In a few seconds he either had his four feet in a bunch, making more revolutions a minute than the bystanders dared count and with the howitzer threatening destruction to everybody within a radius of a quarter mile, or he suddenly tried standing on his head with his heels and howitzer at a remarkable angle in the air.”

Panic set in among the non-Indian dignitaries: some dove into the nearby river, others simply hit the ground, while others ran for the cover of the nearby fort. The Indians simply stood around wondering what all the excitement was about. When the cannon finally went off, the mule’s rear end was pointed at the fort, which absorbed the grape shot. The buffalo mural over the main gate was peppered with shot. No humans were injured and the mule was never seen again.

Having impressed in the Indians with their superior firepower and intellect, the Americans promised the chiefs that they would be paid an additional annual sum for signing the treaty. After signing the treaty, Little Dog, the head chief of the Piegan Blackfoot, said:

“We are pleased with what we have heard today. … The land here belongs to us, we were raised upon it; we are glad to give a portion to the United States, for we get something for it.”

As with all Indian treaties, the Americans assumed that it was immediately binding for the Indians, but it had to be ratified by the Senate before it was binding to the United States. The Commissioner of Indian Affairs, in retaliation for Blackfoot and Blood war parties which killed miners who were trespassing in Indian territory, refused to recommend ratification to the Senate. When the government refused to ratify the treaty, the Blackfoot decided that the government had lied to them once again.

Leave a Reply