At the beginning of the twentieth century, there were a number of Indian groups (bands, tribes, or nations) that did not have formal relations with the United States government. Without formal recognition from the United States, these groups did not have reservations and were thus considered “landless” Indians. In Montana, there were several groups of landless Indians who wandered throughout the state, living through temporary jobs and hunting (including poaching). During the early twentieth century, some of the Chippewa and Cree bands were successful in obtaining a new reservation in Montana in spite of opposition by many non-Indians.

In 1902, Chippewa leader Stone Child (also known as Rocky Boy) hired an attorney to write a letter to President Theodore Roosevelt asking that his people be given a home or reservation. In the letter, he indicated that there were 130 people in his band, that they were all American-born, and they were self-supporting. It is apparent that Stone Child wanted to give federal officials the impression that his followers were hard-working, deserving Indians. To end their current hardship, they needed land. While Stone Child claimed that all of his people were American born, in all likelihood his people included Chippewa and Métis who had been born in Canada and who had come to the United States following the Riel Rebellion to escape Canadian retribution.

In 1903, a special Indian agent recommended that the landless Chippewa under the leadership of Stone Child (Rocky Boy) be placed on the Flathead Reservation. This action was favored by both the Commissioner of Indian Affairs and the Secretary of the Interior, and a bill was introduced in Congress to that effect. However, this action was opposed by Montana Republican Joseph Dixon who wanted to open up the Flathead Reservation for the benefit of non-Indian interests (and to enrich himself in the process). The bill did not pass.

In 1905, Stone Child (Rocky Boy) continued to advocate a Montana home for his people. His band camped at the base of Mount Jumbo near Missoula for several days while he talked with Joseph Dixon, the Congressman who opposed the settlement of the Chippewa on the Flathead Reservation.

The following year, members of the landless Cree and Chippewa bands met with writer Frank Bird Linderman and told him about their desperate condition. They did not have a reservation and had no consistent way to feed themselves. They told him that they had been living on the outskirts of Helena, living on slaughterhouse offal and the town’s garbage.

In 1908, writer Linderman and William Boles, the editor and owner of the Great Falls Tribune began a campaign to convince congress to create a reservation for the landless Cree and Chippewa bands. These men understood that many Montanans, if not most, would be opposed to the creation of another Indian reservation in the state. Their strategy involved a letter-writing campaign targeted at politicians. Artist Charles Russell began to raise money for the Indians and wrote letters in support of the reservation.

Congressman Joseph Dixon wrote to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs regarding Rocky Boy’s (Stone Child’s) band of Chippewa and asked for aid on their behalf. The Indian agent for the Flathead Reservation was sent to investigate their condition and reported that many of the band were actually Canadian Cree.

While congress appropriated $30,000 to establish a home for the Cree and Chippewa, the reservation failed to materialize and the bands continued to wander across the state.

In 1908, about 100 people from Stone Child’s Chippewa band were moved by railroad boxcars to an area around Saint Mary’s Lake near the Blackfeet Reservation. A food-for-allotted-land deal had been supposedly made which opened up 101 allotments for the landless Chippewa. While the landless Indians had been told that the details for the deal had been worked out with the federal government, actually there had never been any such agreement.

In 1909, the federal government determined that there were 120 American-born Indians in the Chippewa band led by Stone Child. Indian Office officials began to survey lands in Valley County for allotments under the General Allotment Act (Dawes Act). However, non-Indians soon objected to relocating the Chippewa in Valley County. Among those who objected with Louis Hill, the owner of the Great Northern Railroad. As usual, when wealthy business owners complain, the government listens and responds. As a result, work on the allotment survey was stopped. While the Indian Office was supposed to serve as the guardian to American Indians, it was in reality more responsive to political pressure from politicians and business interests.

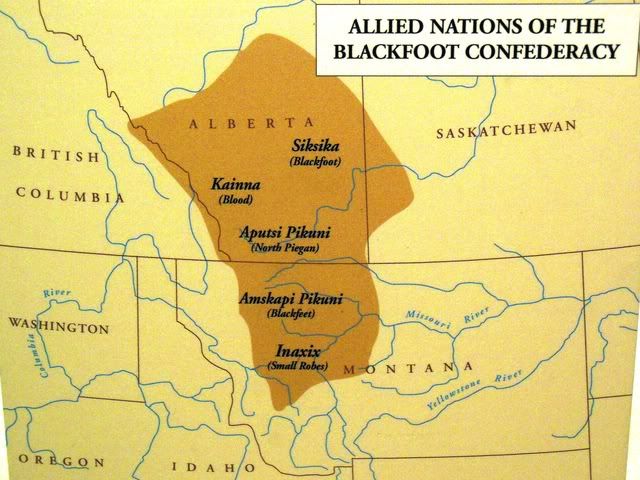

The government relocated landless Cree and Chippewa to Babb, Montana on the Blackfoot Nation in 1910. The government then ordered the land to be surveyed so that it could be allotted to the Cree and Chippewa. The Blackfoot were not consulted about either the relocation or the allotment of their tribal lands.

About 50 Chippewa under the leadership of Stone Child accepted allotments. While Stone Child remained at Babb to take up farming, 150 Chippewa camped near Helena and the Cree under Little Bear returned to the Havre area.

In 1911, the Army announced plans to abandon Fort Assiniboine near the town of Havre. Chippewa leader Full-of-Dew, Cree leader Little Bear, and writer Frank Bird Linderman began a campaign to turn the old fort over to the landless Cree and Chippewa bands as a reservation. The plan was strongly opposed in Havre where the local paper ridiculed Linderman for having a romantic and unrealistic notion of Indians.

In 1912, Fred A. Baker, a superintendent of Indian Schools, was assigned the task of finding lands for the landless Chippewa and Cree. Baker, like most Americans at this time, strongly believed that American Indians should be assimilated into American culture. Assimilation, Baker and other officials in the Indian Office felt, had to be accomplished by transforming Indians into rural subsistence farmers, even though this type of farming was not economically feasible in the urban, market economy that was essential to American culture and life in the early twentieth century.

Baker held a council with Chippewa leader Stone Child, Cree leader Little Bear, and others at the Independence Day Celebration on the Blackfeet Reservation. He then held a separate meeting with Blackfoot leaders. From these two councils, it was clear that neither group favored a plan which called for the Chippewa and Cree to be placed permanently on the Blackfeet Reservation.

Baker visited the Fort Assiniboine Military Reservation after talking with Little Bear who told him that his people had periodically lived in the area. He concluded that the landless Chippewa and Cree should be given a small reservation within the confines of the abandoned Fort Assiniboine Military Reservation. Baker felt that a small reservation would be the first step toward assimilation and that it would remove poverty-stricken Indians from the vicinity of Montana towns.

In 1916, President Woodrow Wilson issued an executive order to create a reservation for the landless Chippewa under the leadership of Stone Child and the landless Cree under the leadership of Little Bear. The tribes were given part of the former Fort Assiniboine and an 8,800 acre park was placed between the tribes and the city of Havre.

Stone Child died of tuberculosis at the age of 70 shortly before the new reservation for his people was created. The new reservation was named Rocky Boy in his honor. Only about 450 Indians, about half of those eligible, chose to settle on the reservation.

Leave a Reply