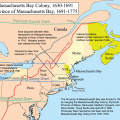

In 1722, Samuel Shuttle, the governor of Massachusetts, declared total war on the Abenaki. Part of the concern of the English colonists was the presence of Jesuits among the Abenaki. The colonial Puritans were vehemently anti-Catholic and particularly anti-Jesuit. Father Sebastian Rasles had strongly encouraged the Abenaki to defend their lands and themselves against the English colonists.

The English colonists viewed North America as a vast wilderness, ignoring the fact that the park-like environment they encountered was, in fact, carefully managed by Native Americans. They viewed the Indians as savage nomads, ignoring the fact that Native agriculture had fed them; ignoring the fact that Indian people lived in permanent villages and raised a variety of crops. The English felt that it was their God-given duty to “tame” the wilderness by exterminating all animals they didn’t like and for this reason they encouraged the killing of coyotes, wolves, and, of course, Indians.

To encourage the killing of these “wild” and “dangerous” animals, the colonial government established a bounty system. To get paid the bounty, hunters had to provide proof of the kill: for this they submitted coyote skins, wolf skins, and red skins (usually the scalps or heads of the Indians they had killed). Some colonists earned their livings through bounties.

In January 1725, Captain John Lovewell organized a militia group to hunt Indians. With the bounty set at £100, Lovewell and his militia members saw killing Indians for the bounty as a way to get rich. In his book The Forgotten America, Cormac O’Brien describes Lovewell’s decision to hunt Indians this way: “A farmer with little to do in the winter but fight off boredom, he decided to raise a company of volunteers, go off into the woods, and cash in on the government’s offer of scalp money.”

The group set out to attack the Abenaki village of Pigwacket (near present-day Fryeburg, Maine), but they changed plans when they came across the tracks of an Indian party heading south. They followed the tracks and came across and Indian camp.

At about 2:00 AM on February 20, the sixty-two English bounty-hunters formed a semi-circle around the sleeping camp. Lovewell fired first and the others followed. One surviving Abenaki man jumped up and began to run and the English set their attack dogs on him. The English stormed the camp, clubbing to death any who had survived the volley of bullets and then scalping all of them. They then took the Abenaki guns (which were of French manufacture and considered quite valuable) and other souvenirs.

When the militia arrived in Boston, they proudly displayed ten scalps which they hoisted on poles for all to see. They were greeted as heroes. They were paid £1,000 by the General Court and they sold their booty for another £70. At this time, this was a lot of money.

Having found bounty hunting for “red skins,” Lovewell decided to raise yet another militia and to enrich himself even further. By spring, Lovewell had signed up 46 men for another bounty expedition hunting Indians for profit and fun. Among those who joined the expedition was Jonathan Fry, a twenty-year-old graduate of the Harvard Divinity School. Fry was to be the group’s chaplain, seeking God’s help in their slaughter of Indians.

Once again, the initial target was the Abenaki village of Pigwacket which was believed to be friendly to the hated Catholic Jesuits. They set out in April, in good weather. On Sunday, May 9, just a short distance from an Indian village, Fry called the men together for a prayer service. The service, however, was interrupted by a gunshot. The English rushed to the shore of a pond where they saw a lone Indian hunting ducks.

Lovewell told his men to leave their blankets and gear so that they could move in quickly to kill the Indian. They quickly surprised the hunter who was carrying some dead ducks and two muskets. The hunter fired one of the muskets, which had been loaded with shot for duck hunting, and wounded two of the English militia. Fry and another man returned fire, killing the hunter. Fry, the group’s chaplain, then scalped him so that he could claim the bounty.

While the English were busy killing and scalping the Abenaki duck hunter, a party of Abenaki under the leadership of Paugus, a Mohawk who had become an Abenaki war leader, were in canoes. When they heard the gunfire, they put ashore and happened to find the English camp. They concealed themselves and waited for the English to return.

The English returned to their camp, basking in the victory over the lone hunter. As they became aware of the fact that their blankets and gear were missing, the Abenaki opened fire. As the battle raged, the surviving English took refuge on a small peninsula on the pond. From here their accurate rifle fire could hold off the Abenaki.

Among those killed in the battle were the English leader Lovewell, the Abenaki leader Paugus, and the Abenaki spiritual leader Wahwah. Twenty of the English bounty hunters survived.

The Battle of Saco Pond, as it was later called, became glorified in American history and literature. In 1820, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wrote “The Battle of Lovewell’s Pond” and in 1824, the Reverend Thomas Cogswell wrote “Song of Lovewell’s Fight.” In the histories and in the literature glorifying the battle, however, the initial cause—hunting Indians for their bounty—was generally omitted.

Leave a Reply