Mormons and Indians

When Europeans began arriving in the Americas they brought with them the firm belief that all knowledge, including the history of the world, was contained in a special holy book which had been compiled from the oral traditions of southwest Asia. They were a bit surprised, therefore, when they encountered the aboriginal people of the Americas, who eventually became known as American Indians, who were not mentioned in that holy book. Some of these Europeans felt—and a few continue to feel—that this meant that American Indians were not to be considered human and, like other wild animals, were to be exterminated so that European “civilization” could prosper. Others worked around this failing of the book by making up creation stories which tied the Indians into the mythical histories of southwest Asia.

From the American Indian viewpoint, the European-book religion seemed strange, irrelevant, and unreal. The Europeans quickly found that conversion worked better if economic and military force were used.

Everything changed in 1823 when an angel led Joseph Smith to a hillside near Manchester, New York, and showed him golden plates engraved with strange characters. After months of concentrated work using a special instrument, he was able to translate the plates and published hundreds of pages of history, prophecy, and poetry that provided the foundation for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (the Mormons). This new religion, and its book, were different in that it included the supposed history of Indian peoples. The Book of Mormon teaches that Indians had descended from Israelite peoples who had migrated to the American continent prior to the Babylonian captivity. Thus, the Mormons viewed Indians as Children of Israel who could be incorporated into God’s Latter-day Kingdom.

According to the Book of Mormon, American Indians were descendants from Laman and were therefore called Lamanites. Laman was the rebellious son of Lehi who had left the Old World and sailed to the Americas in the seventh century BCE. In the Americas, the Lamanite had grown distant from the teachings of God, become fierce and warlike, and had acquired a darker skin color. Robert McPherson, in a chapter in A History of Utah’s American Indians, writes: “From a purely ideological point of view, the Mormons believed that the Indians were a remnant of a people who fell out of grace with God, were given a dark skin as a sign of their spiritual standing, and who now lived in an unfortunate condition awaiting restoration to an enlightened state.”

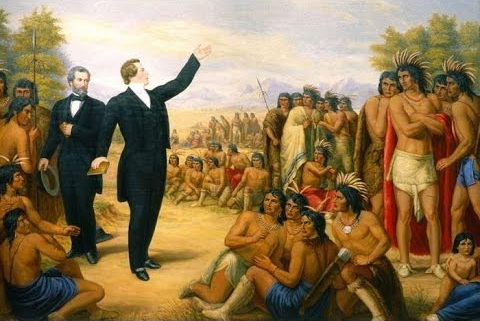

Since American Indians, according to the Book of Mormon, were descended from the Israelites–God’s chosen people–there was to be a special emphasis on the conversion of Indians. Floyd O’Neil and Stanford Layton, writing in the Utah Historical Quarterly, say: “To the Mormons, then, redemption of the Indians (Lamanites) was a prophecy to be fulfilled and a scripture to be vindicated.”

This special emphasis on converting Indians was put to the test when the Mormons were forced to flee from the United States and establish themselves in Utah where they would be surrounded by Indians.

The first Mormon settlers arrived in Utah in 1847 and they were soon followed by a stream of Latter-day Saints seeking the promised land. Following the European settlement pattern, they sought to support themselves through agriculture. The Gosiute tribe living in the area showed them some of the wild edible plants, such as the sego lily root, as a way of surviving until the Mormon’s crops could be harvested.

The Mormons, like other Europeans, disregarded Indian title to the land. From the Mormon perspective the land belonged to the Lord, which meant that only the priesthood could apportion it. The apportionment of the land was to be based on the principles of stewardship. Gary Tom and Ronald Holt, in their article in A History of Utah’s American Indians, write: “Justification for taking the land was given by the Mormon church and its members, including the idea that the Indians were not making efficient use of the land and therefore the Mormons had the right to take it over because they could support more people by their methods of agriculture than the Indians could.”

The Mormon expansion was fairly rapid, driven by the need to acquire land for converts. The new Mormon settlements took the best farmlands and the best water sources. Indians were often employed to help prepare the fields and for various household chores.

Mormon men who were called or appointed as missionaries learned the Indian languages, worked with the tribes, and then attempted to lead them into the fold of Christ’s church. In order to be saved, the Indians first had to be “civilized,” which meant that they had to assimilate into a Euro-American way of life. Indian people often resisted the attempts to change their lifestyles.

In summarizing Mormon interactions with Indians, Thomas Alexander, in his book Utah, the Right Place: The Official Centennial History, writes: “The attitude of the Latter-day Saints toward the Indians represented a convergence of theology, Euro-American imperialism, and racism.”

In an article in the Utah Historical Quarterly Catherine Fowler and Don Fowler write: “Mormon ideology regarding the origin and identity of the Indians generally was responsible for some favorable attitudes and policies toward them, but it may also have been a contributing factor in maintaining a degree of social distance between groups.”

Today, Mormons continue their missionary efforts among American Indians. The missionary experience is probably more important to the young Mormons than it is to the Indians.