American Indians in 1915

One hundred years ago, in 1915, most Indians were not citizens even though U.S. policies called for the full assimilation of Indians and the total destruction of the tribal lifestyles. At the same time, there were a number of prominent Indian voices—Indian people who were writing books, directing museums, and organizing Indian groups. Outlined below are some of the Indian events of 1915.

Federal Government:

In the federal bureaucracy, the person most directly involved with Americans Indians was the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, a political appointment whose office was in the Department of the Interior. The Commissioner of Indian Affairs writes: “I repudiate the suggestion that the Indian is a vanishing race. He should march side by side with the white man during all the years that are to come.”

The Board of Indian Commissioners released a report showing that many Indian irrigation projects were actually operated to benefit non-Indians rather than Indians. With regard to irrigation projects on Montana reservations, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs reported: “Careful consideration of the rights of the Flathead, Blackfeet, and Fort Peck Indians has convinced me that the conditions under which the cooperative irrigation work on these reservations has been done in the past is not for their best interest, and that its continuance would be a great injustice to the Indians.”

Blackfoot leaders Curly Bear, Wolf Plume, and Tail Feathers Coming Over The Hill visited Washington, D.C. to complain about the renaming of mountains, lakes, rivers, and glaciers in Glacier National Park in Montana. The Indians wanted Blackfoot names used and they were promised that in the future only Indian names or their translations would be used.

Hunting and Fishing Rights:

While many of the nineteenth century treaties with Indian nations contained sections in which the Indian nations explicitly retained their traditional fishing, hunting, and gathering rights, the states ignored these rights.

In Washington state, the government passed new fishing regulations which narrowly interpreted Indian treaty rights. Indians could fish off reservation without a license, but only if they were within five miles of the reservation boundary. Since the state of Washington did not recognize Indians as citizens, they are unable to get fishing licenses. It was not uncommon for Indians to be arrested for fishing at their traditional fishing sites.

Also in Washington, Alec Towessnute, a Yakama, was arrested for fishing at Prosser Falls, a usual and accustomed Yakama fishing place. It was, however, more than five miles from the reservation and Towessnute did not have a state license. A county judge ruled that he had a treaty right to fish without a license. The state appealed the case to the state supreme court.

In Washington, John Alexis, a Lummi elder, was arrested for fishing without a license and during a state closure. At his trial, testimony was provided regarding the treaty rights of the Point Elliot Treaty. The judge concluded that Alexis was subject to state law in spite of the treaty.

In Michigan, state and local officials began arresting and fining Ottawas for hunting and fishing without a license.

Organizations:

In New York, the Tepee Order of America was established by urban Indians to stress a common Indian experience. It was a secret, fraternal organization which was modeled after Freemasonry. Officers held titles such as Head Chief and Medicine Man.

In Kansas, the Society of American Indians (SAI) held their fifth annual conference with the theme “Responsibility for the Red Man.” Dr. Carlos Montezuma (Yavapai), in an address entitled “Let My People Go,” condemned the Bureau of Indian Affairs and called for the abolition of reservations. Over 25 tribes were represented at the conference.

The Boy Scouts of America incorporated more Indian lore into its program with the founding of the Order of the Arrow, a camping fraternity. Initiation into this fraternity involved Lenni Lenape legends.

In Washington, the Duwamish, a tribe not recognized by the federal government, are organized and select a board of directors. They were assisted by the Northwest Federation of American Indians.

Museums and Expositions:

In New York, the State Museum exhibited a series of six dioramas on Iroquois life created by Arthur Caswell Parker (Seneca). The dioramas provided illustrations of the various stages of cultural evolution as proposed by anthropologist Lewis Morgan. The dioramas were intended to educate the general public about American Indians.

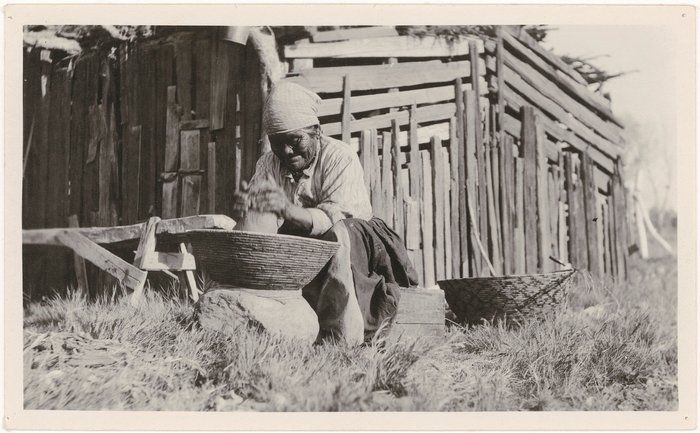

In California, the Panama California Exposition was held in San Diego. The director of the American Institute of Archaeology in Santa Fe, New Mexico was hired to develop exhibits on the evolutionary progress of humans. Anthropologists from the Smithsonian Institution were consulted in preparing exhibits on physical evolution, cultural evolution, and the native races of the Americas. The Painted Desert exhibit, financed by the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad, included a Pueblo Indian village showing Indians living a simple hand-to-mouth existence. San Ildefonso potter Maria Martinez and her husband Julian conducted pottery demonstrations at the Exposition.

Education:

In Kansas, Winnebago educator Henry Roe Cloud opened the Roe Indian Institute as a college preparatory school for Indians. Henry Roe Cloud attended the Auburn Theological Seminary and had been ordained as a Presbyterian minister. He was inspired by a missionary couple, Walter and Mary Roe, and incorporated their name into his and initially used it for the name of his school. The school was later renamed the American Indian Institute.

In Arizona, the Hopi boarding school at Keams Canyon was judged to be in dangerous condition and was closed. The children were enrolled in reservation day schools.

President Wilson appointed Long Lance (Lumbee) to the military academy at West Point. The press picked up the fascinating story of the “full-blooded Cherokee” who was the first Indian appointed to the academy. Long Lance had not fully revealed his mixed blood heritage in his application. Long Lance later failed to pass his entrance exams (perhaps deliberately) and did not actually enter West Point.

Books and Art:

Dr. Charles Eastman (Sioux) published The Indian Today. Dr. Eastman wrote: “It is the aim of this book to set forth the present status and outlook of the North American Indians.”

In a chapter entitled “The Indian in College and the Professions,” he wrote about Carlos Montezuma, a Yavapai physician whose practice was in Chicago: “He stands uncompromisingly for the total abolition of the reservation systems and the Indian Bureau, holding that the red man must be allowed to work out his own salvation.”

Kiowa writer Joseph K. Griffis published Tahan: Out of Savagery, Into Civilization in which he wrote: “The trouble is that so many of us go out in the world and pass as white men. At schools and college they are passing as white men until they try to forget they are a part of the Indian people.”

George Bird Grinnell’s The Fighting Cheyennes was published. Sherry Smith writes in The View from Officers’ Row: Army Perceptions of Western Indians: “At a time when the vast majority of Anglo-Americans showed interest only in the army’s stories, Grinnell collected those from the other side of the battleline.”

James E. Fraser’s equestrian statue, “The End of the Trail,” was shown at the San Francisco Exposition. Flathead author D’Arcy McNickle, in his book Native American Tribalism: Indian Survivals and Renewals, wrote: “Reproductions in miniature of this doleful composition had wide distribution as parlor ornaments and carried into middle-class homes the idea that Indian destiny had run its course.”

In California, linguist Edward Sapir phonetically recorded six traditional Yahi tales told by Ishi.

In Washington, Thomas Bishop began recording Indian elders’ memories of U.S. treaty promises and comparing them to the text of the treaties. Historian Alexandra Harmon writes in her book Indians in the Making: Ethnic Relations and Indian Identities Around Puget Sound: “Bishop’s stated aim was to educate officials who had either forgotten the treaty promises or ignored the troubles plaguing Indians sixty years later.”

Tourism and Sports:

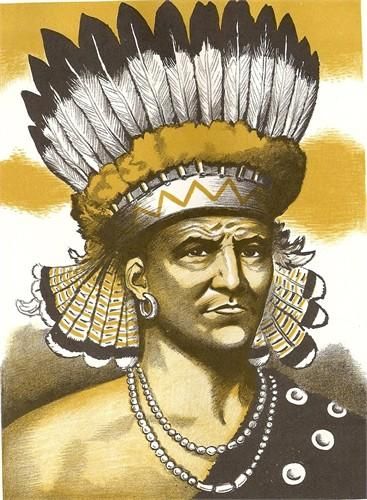

In order to promote tourism in Montana’s Glacier National Park, the Great Northern Railway produced a movie entitled A Day in the Life of a Glacier Park Indian. The film is based on a successful Broadway play called The Redskin. The Great Northern Railway took six Blackfoot to the San Francisco Exhibition where they presented lectures, movies, and transparencies about Glacier National Park.

In Wyoming, the residents of Lovell sought National Landmark status for the Big Horn Medicine Wheel (48BH302). They saw it as a means to attract tourists into the area and thus help develop the local economy.

The Cleveland professional baseball team changed its name to the Cleveland Indians to honor the memory of Louis Sockalexis.

Marriage:

In Oregon, Susan Waters, the daughter of a non-Indian named Martin Davis and an Indian woman named Jane, filed suit challenging the settlement of the Buford Davis estate. She claimed to be the legitimate offspring of a valid marriage and therefore entitled to a half portion of the Davis estates. While 15 witnesses testified that the marriage between a non-Indian man and an Indian woman was common in Oregon and that Davis was married to Jane, the court ruled against her.

Sacred Sites:

In Arizona, President Woodrow Wilson proclaimed Walnut Canyon as a national monument. The site contains many archaeological ruins, some pertaining to the Sinagua people.

States and Territories:

In Montana, a memorial to the Shoshone woman Sacajawea was erected at Armstead by the Montana State Organization of Daughters of the American Revolution.

The Alaska Territorial Legislature passed an act which allowed Indians to become citizens if they had: (1) severed tribal relationships; (2) adopted the habits of “civilization”; (3) passed an examination; (4) obtained endorsement from five non-Indian citizens; and (5) satisfied a district judge.

In Oklahoma, William W. Hastings (Cherokee) was elected to Congress.