The westward expansion of the United States during the nineteenth century was guided by a quasi-religious philosophy of Manifest Destiny: America had been ordained by God to spread its territory across the continent. Americans generally felt that Indians, who supposedly owned the land, were, as an inferior race, destined to be pushed out of the way of progress and become extinct.

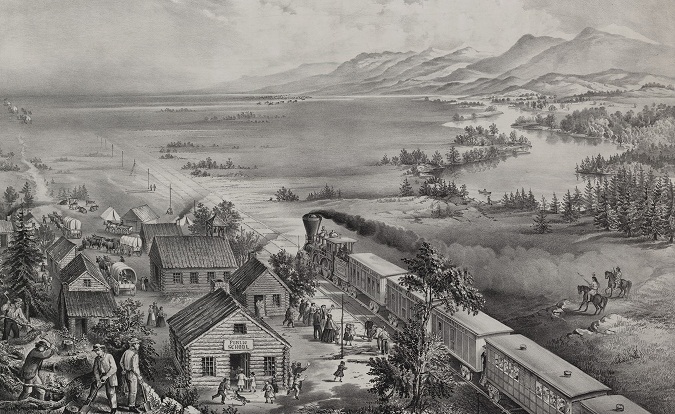

By the middle of the nineteenth century, it was clearly evident railroads would have to play a key role in carrying out Manifest Destiny. It was the railroads which would transport raw materials (minerals, timber, cattle, grain) from the west to the east and manufactured goods from the east to the west. It was envisioned that at least three rail lines—one across the northern portion of the Great Plains, one across the central portion, and one across the southern portion—would be required.

It was not unfettered capitalism that drove the railroads across the Great Plains to the Pacific Ocean, but capitalism nurtured and supported by the federal government. In 1864, President Abraham Lincoln signed legislation which granted “funds to aid the construction of a railroad and telegraph line from Lake Superior to Puget Sound.” Jay Cooke and Company, a Philadelphia banking house, became the financial agents for the railroad in 1869. They broke ground for the new railroad near present-day Carlton, Minnesota in 1870 and soon began grading and track-laying. In 1871, they started construction in the west at Kalama, Washington.

With regard to Indians through whose territories the northern rail line would run, in 1872 William Welsh, the former chairman of the Board of Indian Commissioners, supported the creation of the Northern Pacific Railroad as it would “bring the lawless Indians of the North into subjection, and thus aid effectively the religious bodies charged with bringing Christian civilization.”

In 1872, surveyors were sent out from Fort Rice and from Fort Ellis under military escort to survey the placement of the railroad through the Yellowstone country. This was a direct affront to the Sioux and their allies

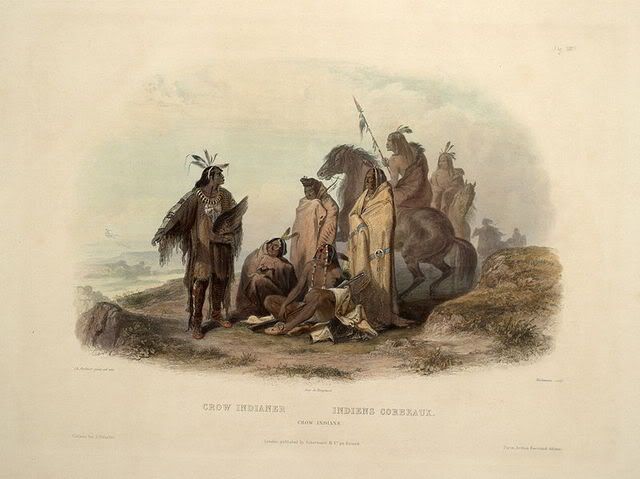

In Montana, about 2,000 Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho gathered at the big bend of the Powder River for a traditional Sun Dance. Following the Sun Dance they launched a major raid against the Crow. More than 1,000 warriors began their invasion of Crow territory when they discovered an American railroad survey party. The survey party of 20 men was protected by about 500 soldiers under the command of Major Baker. The Americans were camped at Arrow Creek (now called Pryor Creek) near present-day Billings.

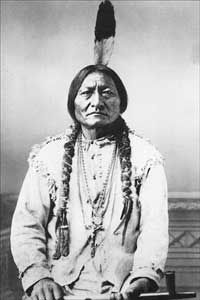

A group of young warriors attacked the sleeping American camp, scattering the army livestock. The following day, a larger force under Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse took a position on the bluffs above the American’s well-fortified site. Some of the warriors fired down at the soldiers and engineers. Sitting Bull walked down from the promontory and sat down within firing distance of the soldiers. There he opened his pipe bag, loaded the pipe with tobacco, and smoked it with the four warriors who had accompanied him. With bullets kicking up dust around them, Sitting Bull calmly and serenely smoked the pipe and passed it to the others. Historian Robert Larson, in his biography Gall: Lakota War Chief, writes: “After each man had taken his puff, Sitting Bull, wearing only two simple feathers and carrying his bow, quiver of arrows, and gun, carefully cleaned out the bowl of the pipe. He then got up and slowly led his anxious comrades back to the main Indian lines.”

The Battle of Arrow Creek (also called the Baker Battle) was more of a skirmish than a battle and there were few casualties. The leader of the surveyors, however, insisted on returning to Fort Ellis and refused to work in the Yellowstone area. This caused the survey efforts to move north to the Musselshell River.

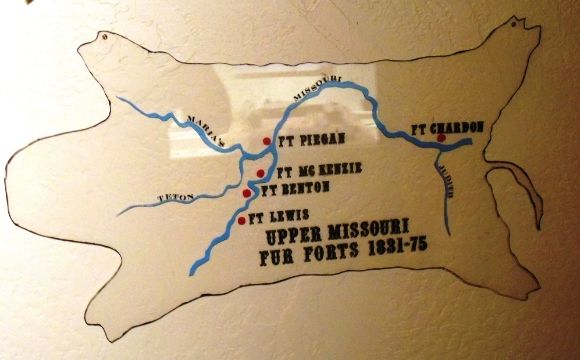

In Montana, a small party of 20 to 30 Sioux warriors under the leadership of Gall encountered a railroad survey party from Fort Buford near the confluence of the Powder and Yellowstone Rivers. Gall’s warriors surprised the sleeping American camp before dawn, but failed to stampede their livestock. The Americans managed to retreat to the west bank of the Powder River.

Gall walked down to the riverbed opposite from the Americans. He placed his rifle on the ground and asked to speak to the leader of the trespassers. Colonel Stanley laid down his pistol and walked to the opposite bank. He asked Gall to meet him on a sandbar in the middle of the river, but Gall refused. Stanley then broke off the talks and there was an immediate exchange of gunfire.

At this point, Sitting Bull arrived with a large war party. However, the Americans were equipped with Gatling guns and easily drove the Sioux warriors back.

In spite of Indian opposition to the intrusion of the railroad, work continued. By 1873, the track from the east had reached Bismarck, North Dakota. However, Jay Cooke and Company went bankrupt with a 1,500 mile gap between the two ends of the track. In 1875, the Northern Pacific Railroad was organized under the leadership of Frederick Billings and by 1878 construction had begun again.

In 1881, the Northern Pacific reached the Yellowstone River at Miles City, Montana. This allowed for the direct shipment of buffalo hides to the east and increased commercial buffalo hunting. In 1883, the last spike of the Northern Pacific Railroad was driven at Independence (now Gold) Creek in Montana, marking the completion of the first of the northern transcontinental railroads.

Leave a Reply