In 1967 the Yellowtail Dam on the Bighorn River was completed in the traditional territory of the Crow Indians in Montana. The dam was named after Robert Yellowtail, a prominent Crow tribal member. The construction of this dam stands as a symbol of the arrogance of the United States government and the total disregard of the rights of Indian people by the governmental agency which is supposed to protect those rights.

The Crow:

The Crow were once a part of an ancestral tribe which included the Hidatsa which lived in the eastern woodlands. Archaeologists suggest that the Crow moved out onto the Great Plains of Montana and Wyoming in two migrations. The Mountain Crow moved out first, sometime in the 1500s. Then a century later, the River Crow followed them. Crow historian and elder Joseph Medicine Crow describes the migrations this way:

“Way back in the 1500s, what might be called our ancestral tribe, lived east of the Mississippi in a land of forests and lakes, possibly present day Wisconsin. They began migrating westward around 1580 until they crossed the Mississippi to follow the buffalo. As far as the Crows are concerned, they separated from this main band in about 1600-1625.”

By the time the first Americans began to enter into Crow territory in the early 1800s, there were three separate and distinct groups. The two largest groups were the River Crow who ranged north of the Yellowstone River and the Mountain Crow who lived south of the Yellowstone and farther west. The third group, the Kicked-in-the-Bellies (also known as Home-Away-from-the-Center), lived in the same area as the Mountain Crow.

The name Kicked-in-the-Bellies came from an incident when the Crow first encountered horses and one of them was kicked by a colt.

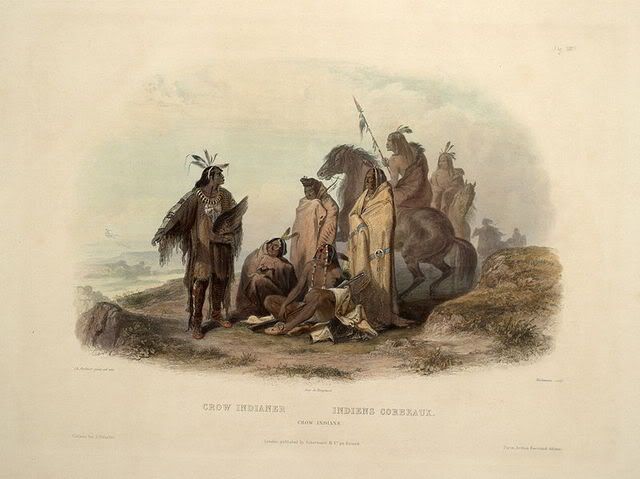

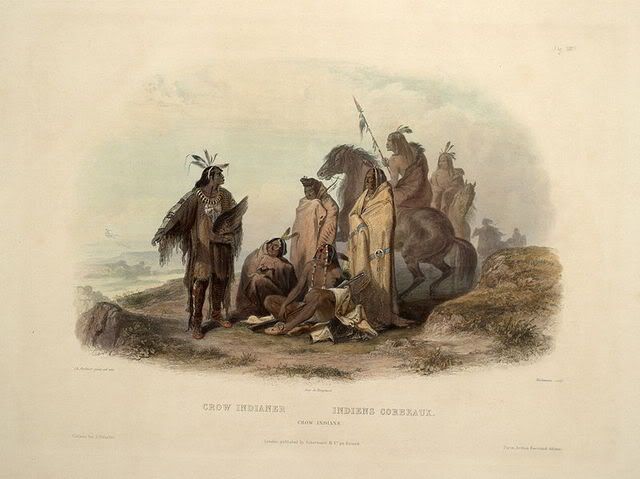

A nineteenth century painting of Crow Indians is shown above.

The Crow Treaties:

The United States Supreme Court has interpreted the Constitution as meaning that Indian tribes are domestic dependent nations. Thus, in dealing with Indian tribes as sovereign nations, the United States negotiated treaties (i.e. international agreements) with them.

The first treaty signed by the Crow was in 1851 at the Fort Laramie Treaty Council. The purpose of the council and of the resulting treaty was to establish peace between the United States and the tribes, including a promise to protect Indians from European-Americans, and to stop the tribes from making war with one another. At the Fort Laramie Treaty Council, an area or territory for each tribe was defined. As there were no River Crow at the Council, the Mountain Crow version of their geographic rights and hunting areas was used and it was assumed by the Americans to be binding to all of the Crow tribes.

In 1864, Congress passed the Organic Act which organized the Territory of Montana. Section 1 of the act states:

“That nothing in this act contained shall be construed to impair the rights of person or property now pertaining to the Indians in said territory so long as such rights remain unextinguished by treaty between the United States and such Indians…”

Sidney Edgerton was appointed as territorial governor and ex-officio superintendent of Indian Affairs. The new territorial governor said:

“I trust that the Government will, at an early day, take steps for the extinguishment of the Indian title in this territory, in order that our lands may be brought into market.”

One of the first actions of the newly formed Montana Territorial Assembly was to pass a resolution calling for the expropriation of all Crow lands. The acting governor attempted to negotiate a treaty in which the Crow would give up all of their lands in the new Montana Territory. An attempt to invite the Crow leaders to a treaty council failed when runners failed to locate any of the Crow tribes.

In 1867, two of the Crow tribes-the Mountain Crow and the Kicked-in-the-Bellies-once again met with American treaty negotiators at Fort Laramie. The Americans told the Crow leader:

“We wish to separate a part of your territory for your nation where you may live forever.”

The Americans promise that non-Indians will not be allowed to settle on Crow lands. The principal Crow speaker was Blackfoot who reminded the commission of the promises made to them in 1851, but which were never kept by the Americans. He shouts at them:

“We are not slaves; we are not dogs!”

Bear’s Tooth reminded the Americans:

“your young men have devastated the country and killed my animals, the elk, the deer, the antelope, my buffalo. They do not kill them to eat them; they leave them to rot where they fall.”

In 1868, the Mountain Crow, the Kicked-in-the-Bellies, and the Americans again met in council. The River Crow were not present. The Americans proposed a drastic reduction in the Crow tribal area which was established in 1851: from 38.5 million acres to 8 million acres. All of the Crow lands in the new state of Wyoming were to be ceded to the United States. Crow leader Blackfoot (Sits in the Middle of the Land) and ten others signed the treaty. The Crow leaders assumed that the United States would negotiate a separate treaty with the River Crow.

Two months after signing the treaty with the Mountain Crow and the Kicked-in-the-Bellies, the River Crow sign their own treaty with the United States. However, this treaty was buried and forgotten by Congress and was never voted on. Consequently, the treaty with the Mountain Crow and the Kicked in the Bellies was considered by the government to be the Crow treaty and the River Crow became invisible to the government.

In 1934, American Indian policy changed dramatically with the passage of the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA). Under the IRA, tribes could decide to reorganize their tribal governments and adopt constitutions. The Crow, however, rejected reorganization under the IRA. In 1948, the Crow wrote their own constitution which established a general council in which every adult member of the tribe is a council member and is entitled to vote in council meetings.

The Dam:

American Indian policy in the United States is administered by the Bureau of Indian Affairs which is a part of the Department of the Interior. Ultimately, the person responsible for Indian affairs is the Secretary of the Interior. While the Department of the Interior may have a trust responsibility with regard to Indian tribes, its primary focus has been (and some feel still is) administering Indian resources in the best interest of non-Indian commercial entities.

In 1951, the Department of the Interior offered the Crow $1.5 million for the Yellowtail Dam site. The Crow rejected the offer. Undaunted by the Crow refusal to sell the site, private interest groups, such as the Big Horn County Chamber of Commerce, Montana’s Congressional delegation, and the Department of the Interior continued to seek support for the dam.

In 1955, the Department of the Interior began a condemnation suit to acquire the Yellowtail Dam site from the Crow. While the Crow had rejected an earlier offer of $1.5 million for the site, the Department of the Interior felt that it had a legal right to the land and intended to pay them only $50,000 for it. The Crow tribal council asked for a lease of $1 million per year for 50 years.

In 1956, under intense pressure from both the Department of the Interior and Montana’s Congressional delegation, the Crow voted to sell the Yellowtail Dam site for $5 million. The vote took place after a 13-hour meeting and passed by less than 60 votes.

The Department of the Interior rejected the Crow offer and seemed committed to condemning the land. The Crow met and discussed the issue for two more weeks. The result was a resolution that still asked for $5 million. Congress accepted the $5 million offer, but President Dwight Eisenhower vetoed it.

In 1957, the Crow, angered by the rejection of their $5 million offer for the Yellowtail Dam site, rescinded the offer and replaced it with a proposal calling for a lease of $1 million per year for 50 years. The Crow were warned by the government and by private individuals that they had no chance of winning in court and that they would probably only get $15,000 to $35,000 for the site. Under pressure, the Crow returned to their original $5 million offer.

In Congress, the $5 million was reduced to $2.5 million plus the right to sue in court for additional compensation. This was the final settlement with Congress dictating the amount rather than negotiating.

The debate over Yellowtail dam divided the Crow: the Mountain Crow opposed the dam, and the River Crow supported the dam. Robert Yellowtail, an outspoken critic of the Bureau of Indian Affairs was one of the main opponents of the dam and protested the decision to sell the dam site to the government.

Yellowtail Dam is shown above.

Leave a Reply