For thousands of years the 1,242-mile-long Columbia River has been central to the lives of the Indian people of the Columbia Plateau region. The river functioned as a superhighway facilitating trade from the Pacific to the Rocky Mountains. The river was also their supermarket providing abundant fish to support the Indian lifestyle. And finally, the river was an important part of Indian spirituality.

Shown above was the Indian fishery at Celilo Falls.

During the nineteenth century there was a flow of Europeans, beginning with Lewis and Clark, who used the river as their highway. By the twentieth century, the Americans, who now claimed ownership of the river, looked at it in a different light. Obsessed with the idea of controlling and changing the natural environment, the Americans almost seemed to worship dams. They saw them as monuments to their engineering skills and to their manifest destiny to control nature. The dams also generated electricity which helped the growth of American businesses and contributed to the wealth of the business owners.

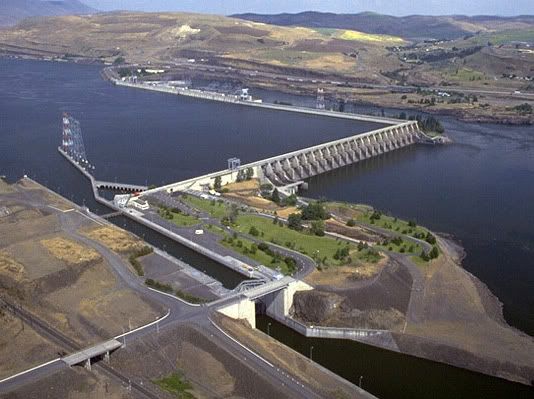

The Bonneville Dam (1937) was the first of 31 federal dams built on the Columbia River and its tributaries. The dams were built for power, irrigation, and to prevent flooding. There was little, if any, concern for the impact of these dams on the economic, social, cultural, and spiritual lives of the many Indian nations located along the river.

Congress authorized the construction of The Dalles Dam in 1950. No input from the Indians whose lives would be negatively impacted by the dam was sought by Congress. While the loss of fishing caused by the dam was deplored, it was felt that the commercial interests of irrigation, power, and shipping outweighed the fish. With regard to the Indians, Congress noted:

“Alternative fishing sites to replace those inundated must be established-by artificial means if necessary, or the Indians paid just compensation for the sites taken.”

The dam was to be constructed by the Army Corps of Engineers, an agency not known for its concern for or its empathy with American Indians.

In 1951, a Yakama tribal delegation-Thomas Yallup, Alex Saluskin, Gealge Seelatsee, and Watson Totus-testified before a Congressional committee about the importance of Celilo Falls on the Columbia River and the impact which the proposed The Dalles Dam would have on their people. When Thomas Yallup testified that Celilo Falls were sacred, he was asked why some other river wouldn’t work as well. Yallup replied:

“The Christian people of the States of Oregon and Washington have recognized our holding the [salmon] ceremony for each year, and throughout the country I believe that the other religions, including the Christian religion, have also backed us up in asking the Government not to take a sacred place, a place that is held sacred by the Indians.”

The Commissioner of Indian Affairs indicated that the Bureau of Indian Affairs would not oppose the construction of The Dalles dam because of the urgent national defense need for power brought on by the Korean War and the Cold War.

With regard to the impact of The Dalles Dam and the loss of Celilo Falls on the salmon in the Columbia River, the regional director of the federal Bureau of Commercial Fisheries stated:

“The Indian commercial fishery would be eliminated and more fish would reach the spawning grounds in better condition.”

The director’s opinion reflects the popular non-Indian belief that if Indian fishing were to be eliminated on the Columbia River, then there would be abundant fish for non-Indian sport fishing. It is estimated that only 10% of the salmon caught in the Columbia at this time were caught by Indians.

In 1952, the U.S. House of Representatives denied funding of The Dalles Dam on the Columbia River until the Army Corps of Engineers began negotiations with the Indians who would be impacted by the dam. Shortly afterwards, representatives from the Corps met with the Umatilla and Warm Springs tribes.

The Army Corps of Engineers was concerned with documenting and measuring the economic value of Indian fishing. The primary questions for which they sought answers were: Which Indians were fishing at Celilo? Did they have a treaty-supported right to the sites? How many fish did Indians catch to sell commercially? How many fish did they take for subsistence use? What did fish buyers and tourists pay for their fish? The answers to these questions would enable the Corps to determine the monetary value of the fishery. The Corps did not consider the cultural value of Celilo Falls or its historic and spiritual meaning to Indian people.

In 1952, the Army Corps of Engineers compiled a special report on the Indian fishery problem regarding the construction of The Dalles Dam. With regard to the desires of the Indians, the Corps reports: (1) the Indians do want The Dalles dam built, (2) if the dam is built, they want full compensation for their losses, (3) they would prefer in-lieu sites rather than monetary compensation, (4) they do not want the matter settled in the court system, (5) they would prefer a settlement prior to the construction of the dam, and (6) they do not want to give up their fishing rights.

In 1952, the Umatilla and the Warm Springs tribes accepted a settlement drafted by the Army Corps of Engineers regarding their losses from the construction of the proposed The Dalles Dam. The Warm Springs tribes accepted the settlement under protest. Both tribes relinquished the right to sue the federal government for further compensation. The settlement came to about $3,700 per enrolled tribal member.

In 1952, the members of the Warm Springs tribes reluctantly signed a contract with the Army Corps of Engineers to cover the damages to the Celilo fishery on the Columbia River which the people suffered as a result of The Dalles Dam. After the deduction of attorney fees and other costs, each member was to receive $145.50. There was no mention of the loss of the fisheries at the Five Mile Rapids and the Spearfish fisheries.

In 1953, Chief Tommy Thompson of the River Indians at Celilo Falls found that Skuch-pa, a sacred stone, was missing. The stone is four feet across and six feet tall and had been used traditionally for ensuring good weather during fishing. Initially it was reported that it had been was removed by the Army Corps of Engineers as a part of its work preparing for The Dalles Dam, but then the Indians found out that a non-Indian had removed it and placed it on his property.

In 1954, the Army Corps of Engineers planned to purchase the Indian homes which would be flooded by The Dalles dam on the Columbia River. However, the Corps had no intention of relocating the displaced residents. The Corps felt that it had only a legal responsibility for paying the Indians the appraised value of their homes and their fish drying shed. This was usually a meager amount that would not cover the cost of an acceptable replacement.

In 1955, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers published a report documenting that the Nez Perce had no legal claim to fishing sites at Celilo Falls on the Columbia River. The Corps invested a great deal of labor and money to avoid compensating the Nez Perce for their claims to the Celilo fishery. The Army Corps of Engineers met with the Nez Perce for two days to discuss their claims. The Corps then recommended an end to negotiations citing Nez Perce intransigence. As long as the Nez Perce insisted that they had traditionally fished at Celilo Falls and would not accept the Army Corps of Engineers version of Nez Perce history and tradition, then the Corps felt that negotiations were meaningless.

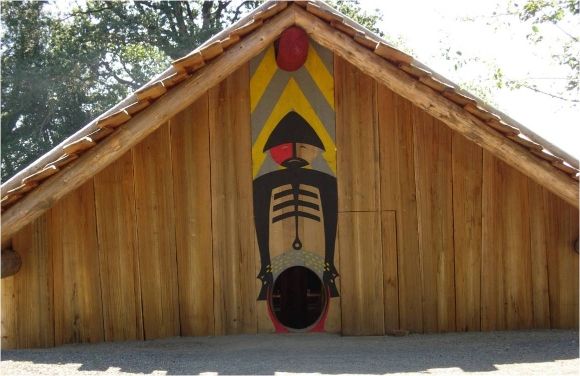

The gates of The Dalles Dam closed in 1957 and the waters of the Columbia River began rising to flood traditional Indian fishing sites, sacred areas, burial sites, and homes. Many Indians stood on the shore openly weeping as the river stopped flowing and began to rise. Celilo Falls, an important resource and spiritual site, disappeared beneath the rising waters. For more than 10,000 years the people had fished in the area between Celilo Falls and Threemile Rapids. The rising waters of the Columbia displaced some of the oldest continuously inhabited village sites in North America. Archaeological sites which had never been studied were destroyed.

The Confederated Warm Springs Tribes received $4 million in indemnity and the Yakama received $15 million. Many non-Indians believed that this money had bought the tribes’ fishing rights, but this was not the intent of the settlement.

In 1958, the salmon runs on the Columbia River plummeted following the completion of The Dalles Dam. The states of Oregon and Washington were determined to conserve the remaining fish, supplementing them with hatchery stocks, for the non-Indian commercial and sports fishers. The number of days for commercial fishing was reduced. The states argued that Indians could only sell the fish they caught during these same days and that they should be limited to selling only those caught with the traditional dip nets.

In 1958, the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) declared that all of the permanent residents of old Celilo Village in Oregon had been provided with comfortable homes at various places up and down the river and elsewhere. However, under the BIA rules only a small portion of the Indians who considered Celilo Village to be their home actually qualified as “permanent” residents. Part of the old village was given by the BIA to the state of Oregon to be used as a public park. The BIA had no concern for the possible Indian use of this land.

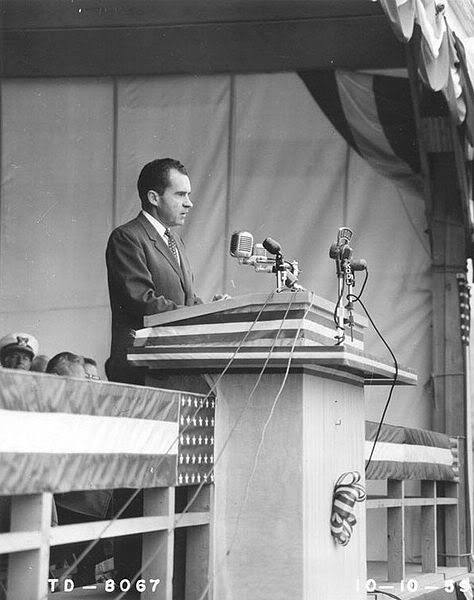

In 1959, Vice-President Richard Nixon pushed the button which started the generation of hydroelectricity at The Dalles Dam on the Columbia River. Senator Richard Neuberger reminded people that

“our Indian friends deserve from us a profound and heartfelt salute of appreciation…They contributed to its erection a great donation-surrender of the only way of life which some of them knew.”

In other words, once again wealth was being transferred from Indians, the poorest people in the country, to wealthy non-Indians. With the construction of The Dalles Dam, Indian people-the Yakama, Warm Springs, Nez Perce, Umatilla, and others-lost an important cultural and economic center which had served them for thousands of years.

In 1959, Chief Tommy Thompson died at more than 100 years of age (some estimated that he was 104). His funeral held at the Celilo longhouse drew more than 1,000 people, both Indian and non-Indian. They came to pay their respects to this well-known leader who had defended Native fishing rights and who had vigorously opposed The Dalles Dam. His leadership of the River Indians who fished at Celilo Falls on the Columbia River had lasted for more than 80 years.

Leave a Reply