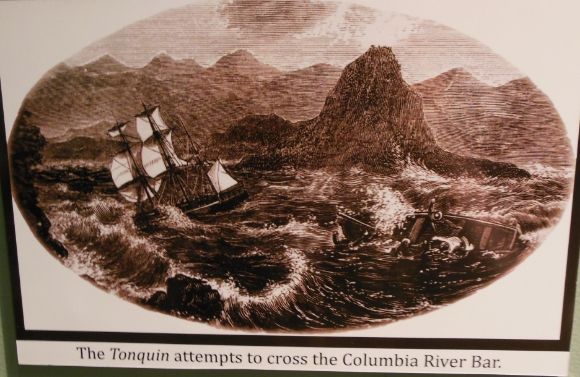

The river known to the Chinook Indians as Hyas Cooley Chuck collides with the Pacific Ocean to create the worst wave conditions on the planet. While Native people crossed the Bar in their large ocean-going canoes, the rough water stopped many of the early European explorers who were looking for the mythical River of the West. In May 1792, the American fur trader Captain Robert Gray waited out nine days of adverse conditions on the Bar before finally crossing into the river. He named the river for his ship, the Columbia Rediviva.

The ship’s young fifth mate kept a journal in which he recorded:

“The Indians are very numerous, and appear’d very civil (not even offering to steal).”

He described the Indians:

“The Men, at Columbia’s River, are strait limb’d, fine looking fellows, and the Women are very pretty. They are all in a state of Nature, except the females, who wear a leaf Apron.”

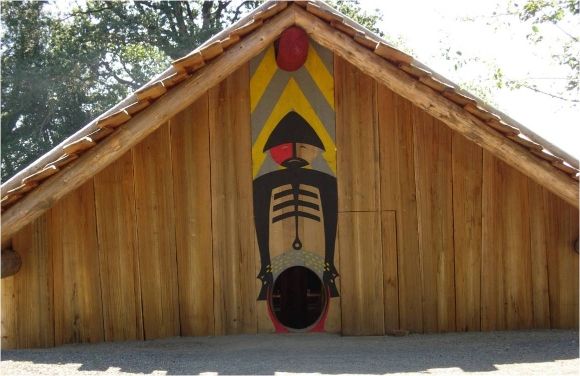

A replica of a Chinook longhouse is shown above.

Among the Chinook men who met with the American fur traders was a young man known as Comcomly, who would later become a major chief.

In 1795, the British trading ship Jane under Captain John Myers sailed into the Columbia River. The ship carried a cargo of axes, chisels, hammers, copper sheets, small bells, paints, clothing, china beads, buckets, firearms, and ammunition to trade with the Chinook.

Soon after Jane, the British ship Ruby under Captain Charles Bishop sailed into the Columbia. The ship traded for furs for eleven days. When the Chinook ran out of furs, the British traded for clamons, a kind of body armor made by the Chinook. These were in high demand by the Indian nations farther up the Pacific coast. The captain noted in his journal:

“The Sea Otter skins procured here, are of an Excellent Quality and large size, but they are not in abundance and the Natives themselves set great value on them.”

Captain Bishop invited Chief Comcomly to spend the night aboard the ship and provided him with a fine coat and trousers. Comcomly then led a Chinook expedition 300 miles upriver to obtain more clamons. Some of these were obtained by less than peaceful trading.

Over the next two decades, Comcomly solidified his leadership among the Chinook bands using a combination of trading skills, diplomacy, and marriage. Some writers report that he had a wife from nearly every tribe in the confederation as well as some outside of the confederacy. With regard to his physical appearance, Comcomly is generally described as being short and blind in one eye.

In 1805, the American Corps of Discovery under the leadership of Meriwether Lewis and William Clark reached the mouth of the Columbia River and established their winter camp, Fort Clatsop, on Chinook land. Thanks to the cooperation of the Chinook and the Clatsop, the Americans were provided with the food that enabled them to survive the winter.

While Comcomly did not greet the Americans when they first arrived, he did sit in council with them at his village later. The Americans provided him with a medal and an American flag. Both Clark and Lewis admired Comcomly’s sea-otter robe and tried to bargain for it. Comcomly pointed to Sacagawea’s belt of blue beads and indicated that is what he wanted for the robe. One of the captains then gave Sacagawea a blue coat for her belt and she gave the belt to Comcomly. The journals do not indicate who finally got the robe.

The Americans generally expressed mistrust and contempt for both the Chinook and the Clatsop. There is some indication that Comcomly also mistrusted the Americans as evidenced by the fact that he did not visit their camp.

In 1810, the Boston ship Albatross under the command of Nathan Winship sailed up the Columbia River past Chinook chief Comcomly’s trading headquarters. About 45 miles upstream, the Bostonians built a fort. As an old hand in the Pacific fur trade, Winship wanted to bypass Comcomly’s monopoly on trade with the Indians of the Columbia River and to establish direct trade with the Indian nations upstream.

Comcomly was insulted by this action, and a delegation of warriors, all fully armed, paddled to the newly established fort. There was some hostile confrontation in the form of shooting and shouting. One of the Bostonians recorded:

“Much to our chagrin we find it impossible to prosecute the business as we intended, and we have concluded to pass farther down. On making this known to the Chinooks they appeared quite satisfied and sold us some furs.”

The Bostonians abandoned their enterprise after eight days.

The first permanent settlement of American traders at the mouth of the Columbia River came in 1811when the Pacific Fur Company established Fort Astoria. The first group of Astorians arrived on the ship Tonquin. Two of the American partners, Duncan McDougal and David Stuart came ashore in a small boat and met with Chief Comcomly. They found Comcomly agreeable to the idea of a trading post for his people.

When the Americans set out to return to their ship, Chief Comcomly pointed out that the rough conditions on the river would make the trip across the Bar difficult in their small vessel. The Americans didn’t listen and set out anyway. Chief Comcomly, knowing that they couldn’t make it, simply followed in one of his canoes. When the traders’ boat capsized, Comcomly rescued them. Comcomly took the wet men ashore, built a fire, dried their clothes, and then took them to a Chinook village. He advised them to wait until conditions were more suitable for the return to their ship.

The Americans found that the Chinook village consisted of about 30 very large, wood houses. For three days they were entertained in the village (it is assumed that this included having sex with Chinook women). Then Comcomly took his guests back to their ship in his royal canoe. This helped firm up the good relations between Comcomly and the traders.

The trading alliance with Fort Astoria added to the prestige and wealth of the Chinook in general and Comcomly in particular. The power which Comcomly held over the trade along the Columbia can be seen in the log of the Pacific Fur Company. Fort Astoria was visited by few Clatsop and Chehalis and when asked about why they didn’t trade directly:

“They told us that being cautioned by the Chinooks, against coming, as we were very inveterate against their Nation, for their conduct to former Visetors they did not wish to put themselves in our power. This we made them sensible to be an egregious falsehood imposed upon them by the Chinooks, merely to monopolize the Trade….”

In order to solidify the alliance even further, McDougal dispatched one of his clerks with an important message for Comcomly: he wanted to marry one of Comcomly’s daughters. Comcomly, who had many daughters, was pleased to oblige.

Comcomly made almost daily visits to Fort Astoria and was admitted to the most intimate councils of his son-in-law. He was also given his own quarters in the fort.

Word that the United States was at war with Britain reached the Astorians in 1813 along with a party of Nor’westers (traders from the North West Company-owned by the British). The Nor’Westers informed the Astorians that a British war ship was on its way to take over the fort and consequently the Astorians hastily sold the fort to the Nor’westers.

When the British warship Racoon arrived, Fort Astoria was renamed Fort George. Comcomly was soon aboard the Racoon telling the captain that he was delighted to see a British ship on the river. He left with a British flag, coat, hat, and sword. The following day, he wore his new regalia to Fort George. Duncan McDougal, the working partner of the Pacific Fur Company who sold the company to the Nor’Westers, stayed on at the fort in the employ of the Nor’Westers. This meant that Comcomly retained his connections with the trading post.

In 1821, the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) and the Nor’westers merged. In 1824, HBC governor George Simpson and Dr. John McLoughlin, the new chief factor for the fort, arrived at Fort George. Simpson was not pleased with either the fort or with Comcomly’s relationship to it. With regard to Comcomly and the Chinook, Simpson said:

“They never take the trouble of hunting and rarely employ their Slaves in that way, they are however keen traders and through their hands nearly the whole of our Furs pass, indeed so tenacious are they of the Monopoly that their jealousy would carry them the length of pillaging and even murdering strangers who come to the Establishment if we did not protect them.”

HBC moved their trading operation 90 miles upriver where they established Fort Vancouver. This moved deprived Comcomly of his role of middleman, thus diminishing his prestige and wealth.

Comcomly had an excellent understanding of the Columbia River and its dangerous Bar. With the increasing number of ships attempting to cross the Bar bringing in trade goods and supply, Comcomly’s skill as a pilot was soon in great demand. His skill as a pilot earned him the respect of the HBC captains as well as Chief Factor McLoughlin.

In 1830, the epidemic known as the “cold sick” (possibly malaria) swept through the Native populations of the region. One of the victims of this epidemic was Comcomly. He was estimated to be in his mid-sixties when he died. His body, together with his war weapons, ceremonial dresses, and other possessions, was placed in a canoe. The canoe was placed on a raised platform near Point Ellice.

Leave a Reply