Ranald MacDonald, Teacher of English to the Japanese

In 1853 Commodore Matthew C. Perry brought the American Navy to Japan and forced Japan to end its policy of isolation from the rest of the world. In the negotiations, the Japanese government had interpreters who spoke English. Since Japan had isolated itself from the rest of the world and had barred foreigners from their island nation, how did Japanese interpreters come to speak English? The answer to this question lies in the hidden history of American Indians.

About Japan:

At the beginning of the seventeenth century, Japan had closed its doors to the outside world. This was in response to aggressive Christian missionaries from Spain and Portugal who were converting Japanese and threatening traditional Japanese society. The Shogunate expelled the missionaries and then forced the converts to revert to Japanese religions or die.

After 1635 and the introduction of Seclusion laws, foreigners were forbidden to enter Japan and the Japanese were not allowed to leave. Some foreign trade was allowed from the southern port of Nagasaki, but here the foreigners, mostly irreligious Chinese and a few Protestant Dutch, lived in prison-like conditions. Inbound ships were allowed only from China, Korea, and the Netherlands. These ships, known as Red Seal Ships, were required to have a permit from the Shogun.

With the discovery of Hawaii by Americans and Europeans in the late eighteenth century, the establishment of Fort Astoria in the early nineteenth century, and the development of the fur trade in the Pacific Northwest generated a great deal of interest in Japan. A lucrative system of triangular trade developed in which American ships acquired furs from Indians along the coast of present-day Oregon and Washington, then took these furs to China where they were traded for Chinese goods, and then transported their Chinese cargoes to the Northeastern United States. Now if Japan could be added to this trade, American and English businessmen speculated, even greater profits could be made.

In 1822, John Quincy Adams urged that:

“it was the duty of Christian nations to open Japan, and that it was the duty of Japan to respond to the demands of the world, as no nation had a right to withhold its quota to the general progress of mankind.”

Ranald MacDonald:

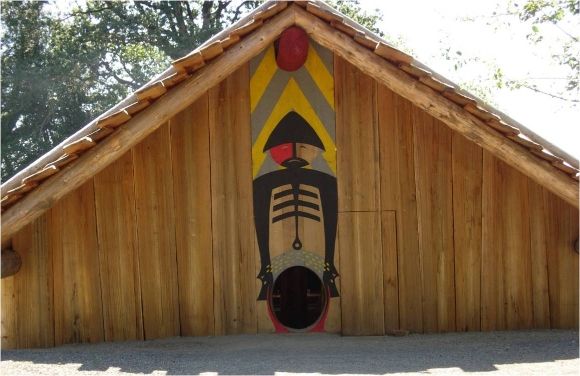

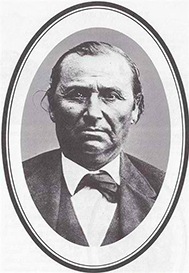

Ranald MacDonald was born near present-day Astoria, Oregon in 1824. His mother was generally called Princess Raven or Princess Sunday. Her Chinook name was Koale’xoa and her father was the prominent Chinook leader Comcomly MacDonald’s father, of Scots heritage, was Archibald McDonald, the Chief Factor of the Hudson’s Bay Company.

Shortly after he was born, the Hudson’s Bay Company moved its operations from Fort George (now Astoria, Oregon) 90 miles upstream to Fort Vancouver. As a Métis child in a fur trading community and household, he grew up hearing a mixture of languages-French, English, Gaelic, Chinook, Iroquois, and other Indian languages. Thus he was able to quickly adapt to different cultures.

In 1833, the Japanese ship Hojun-maru washed ashore near Cape Flattery. The ship had set sail more than a year before from the Japanese port of Toba with a cargo of rice and ceramics. A storm blew the ship off course. When the crippled junk made landfall, the Makah captured three Japanese sailors. The Hudson’s Bay Company bought the sailors from the Makah hoping to use them to open up trading with the Japanese. As a child growing up in the Hudson’s Bay Company trading post of Fort Vancouver, he heard many stories about Japan and about the Japanese sailors who had been shipwrecked.

For hundreds and perhaps thousands of years, ships from Japan and China had been riding the Kuroshio (Black) Current from Asia to North America. The Hojun-Maru was not the first crippled Asian ship to make the trip, nor would it be the last. MacDonald, like many others, felt that his Native American ancestry was linked somehow to Japan. The stories of the Japanese ships coming to North America nourished within him the dream of visiting this island nation.

As an aside, it should be noted that the Hudson’s Bay Company, once they had purchased the Japanese sailors from the Makah, transported them first to Fort Vancouver in present-day Washington, and then to London. In London, they were placed on a ship with Christian missionaries to return them to Japan with the hope of opening up Japan to both trade and Christianity. The Japanese, however, fired upon the vessel and refused to allow it to land.

Ranald MacDonald started his formal education by attending a Hudson’s Bay Company school at Fort Vancouver, Washington. At the age of ten he was then sent to the Hudson’s Bay Company school at the Red River Settlement in Manitoba (Canada). After graduating from school, he became a bank clerk apprentice, but soon quit, journeyed to New York City, and looked for a ship to take him to Japan. Failing to find such a ship, he went to Europe and later to San Francisco as a sailor.

One of his shipmates describes him this way:

“a man of about five feet, seven inches; thick set; straight hair and dark complexion…He was a good sailor, well-educated, a firm mind, well calculated for the expedition upon which he embarked.”

In 1848, Ranald MacDonald made a deal with the captain of a U.S. whaling ship in Hawaii. The ship carried him across the Pacific. After successfully taking a number of whales near Japan, MacDonald purchased from the captain a small boat rigged for sailing. With supplies for 36 days and located about five miles from the nearest island, he bid farewell to the ship to set out on his adventure.

He came ashore on Rishiri Island in northern Japan. When he landed he was met not by Japanese but by Ainu, the indigenous people of Japan. The Ainu, whose men have beards and abundant body hair and whose women tattooed their upper lips, do not look Japanese. The Ainu, after welcoming him, turned him over to the Japanese authorities. The first word spoken by the high-ranking Japanese official who first interviewed him was Nippon-jin (Japan-man, indicating that MacDonald looked Japanese).

The Japanese took him to Nagasaki. Here he spent six months as a prisoner. The question of his citizenship at this point in time is interesting: he was Chinook, an American Indian nation, because of his mother; he had been born in Astoria when the British flag was flying there and his father was British; he had been educated in Canada; but at the time of his capture, Astoria had just become a part of the United States.

During his time in Nagasaki he taught English to the Japanese interpreters, Moriyama and Tokojiro, who would later carry out the negotiations with Commodore Perry. He would later write:

“Without boast, I may say that I picked up their language easily, many of their words sounding familiar to me-possibly through my maternal ancestry.”

He also wrote:

“In look, facial features, etc. I was not unlike them; my sea life and rather dark complexion, moreover giving me their general colour-a healthy bronze.”

He was deported from Japan in 1849, but instead of returning to the United States or Canada, he continued traveling around the world. He spent some time working at various jobs in British Columbia and in 1882 moved to the old Hudson’s Bay Company trading post of Fort Colville in Washington.

MacDonald wrote a book about his adventures in Japan and in 1853 left the original manuscript with a friend of his father’s, Malcolm McLeod, in Ottawa. He did not communicate with McLeod again for 25 years. By 1887, he had prepared a second draft of the manuscript and a third by 1891. At this time, however, no publisher was willing to produce the book as public interest in Japan had faded.

By 1891 he had returned to Astoria, Oregon where he was respected as the only lineal descendent of chief Comcomly. He died in 1894 on the Colville Reservation in Washington. As he died in his niece’s arms, his last words were “Sayonara, my dear, sayonara…”

Today, the Japanese remember Ranald McDonald as the “first teacher of English.” There is a monument to him in Nagasaki, Japan. In addition, there is another monument to him in Astoria, Oregon with the inscription written in Japanese.