Henry Cloud was born in 1884 (1882 or 1886 according to some sources) to the Winnebago Bear Clan (or possibly the Bird Clan) on the reservation in northeastern Nebraska. His tribal name was Wo-Na-Xi-Lay-Hunka (“War Chief”). At the age of seven he was conscripted by the Indian police and sent to the Genoa Indian School, a government-run boarding school. Here he learned English, was forbidden to speak his tribal language, and was converted to Christianity. He was then baptized Henry Clarence Cloud.

With regard to his conversion to Christianity, one of his biographers, Joel Pfister, writes:

“Roe Cloud employed Christianity spiritually and emotionally to empower not just himself but his people. Furthermore, organized Christianity gave him access to education and ruling social groups.”

With regard to his experience at Genoa, he would later write:

“I worked two years in turning a washing machine to reduce the running expenses of the institution. It did not take me long to learn how to run the machine, and the rest of the two years I nursed a growing hatred for it.”

Genoa Indian School is shown above.

He was orphaned by the age of 13 and sent to the Santee Mission School where he was trained to become a printer and blacksmith.

In 1901 he was admitted to the Mount Hermon Preparatory School in Massachusetts which had a work-study program through which he could finance his education. While he had been an outstanding student in the Indian schools, he soon found that he was unprepared to deal with the academic challenges of a college preparatory school. The school required all students to complete entrance exams on the first day of school and he passed on the tests in Bible, writing (penmanship), spelling, and geography. This meant that he had to enroll in the Preparatory Department.

In 1904, his financial condition required that he drop out of school for a year and work on a farm.

He graduated from Mount Hermon as salutatorian in 1906 and then attended Yale College. He graduated from Yale in 1910 with a B.A. in Psychology and Philosophy and then went on to earn a Master’s Degree in Anthropology from Yale in 1912. He was the first full-blood Native American to graduate from Yale.

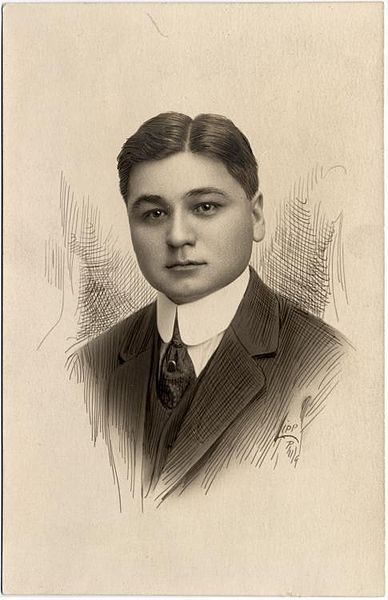

Henry Roe Cloud is shown above.

While an undergraduate at Yale, Henry Cloud attended a lecture by the missionary Mary Wickham Roe who was involved in evangelical Christian mission work among the Arapaho, Cheyenne, and Apache in Oklahoma. Her husband, the Reverend Walter Roe, was the Superintendent of Indian Missions for the Reformed Church. Henry Cloud developed a close relationship with the Roes and adopted their surname as his middle name. After this he was generally known as Roe Cloud.

As an Indian at Yale, Henry Roe Cloud became a celebrity and a proficient orator. He lectured to the public about the deficiencies of the government-run Indian schools and about the stereotype that Indian students were only suited to vocational educations.

In 1910, the Roes sponsored his appearance at the annual Lake Mohonk Conference of Friends of the Indian, an influential and powerful group of non-Indians which stressed the assimilation of Indians into American society. In 1914, he addressed the group:

“Education unrelated to life is of no use. Education is the leading-out process of the young until they themselves know what they are best fitted for in life.”

In 1911, Henry Roe Cloud attended the first conference of the newly formed Society of American Indians at Ohio State University and was on a panel that discussed religious and moral issues.

In 1912, he headed a Winnebago delegation to Washington, D.C. where they met with President William Howard Taft. Taft was a Yale alumnus and his son had been Roe Cloud’s classmate. Roe Cloud’s Yale connections provided him with access to political power and politicians which were not available to reservation Indians.

In 1913 he attended the Auburn Theological Seminary in New York and was ordained as a Presbyterian minister.

In 1915, Henry Roe Cloud opened the Roe Indian Institute in Kansas as a college preparatory school for Indians. This was the first Native American college preparatory school in the country. While it stressed academic study, it also included training in agriculture and the trades. When the school opened, it had only eight students. The school would later be renamed the American Indian Institute. The school closed in 1930 because of financial difficulties.

In 1916, Henry Roe Cloud married Elizabeth Georgian Bender, a Bad River Band Chippewa, who had taught on the Blackfeet Reservation in Montana and at the Carlisle Indian School.

In 1923 an elite panel known as the Committee of 100 was convened by the Secretary of the Interior to advise on Indian policy. Henry Roe Cloud served on this committee and advocated for the establishment of federally funded scholarships for Indians in college. The Committee supported the goal of assimilation, but called for a greater sensitivity to Indian customs and the protection of tribal land.

From 1926 until 1930, he was associated with the Brookings Institute and was involved with the study of Native American issues that resulted in the Meriam Report on “The Problem of Indian Administration.” His primary role was that of a traveling investigator visiting reservations.

In 1931, he went to work for the Bureau of Indian Affairs as a field representative at large, a position that did not require passing the civil service test (which he had earlier failed). One of his investigations dealt with the significant financial mismanagement at Haskell Institute. He recommended that the school revert to a vocationally oriented program and be administered by an educator.

In 1933 he became the superintendent of the Haskell Institute in Lawrence, Kansas which was the largest American Indian high school in the country. Haskell was known for its victorious football teams, its 10,500-seat football stadium, and its strong emphasis on vocational training (particularly agriculture and printing). He was the first full-blood Indian to hold this position. As superintendent he helped lobby for the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934.

Haskell Institute is shown above.

At Haskell, Roe Cloud encouraged students to read Indian history and to examine Indian customs and communal practices. He encouraged them to explore the influences of both individual Indians and Indian groups on American culture. He felt that Indians could give American culture what it lacked: a cultural antiquity which should be valued. He insisted that the so-called “New” World was just as old as Europe and that its history was important. While he felt it was important for Indians to assimilate into American culture, he also felt that they should import the Indian ways of thinking, valuing, and living into the dominant culture.

At Haskell, Roe Cloud gave Indian names to the recreational halls, authorized the teaching of Indian languages, sponsored Indian dances, and reprinted books of Indian legends.

In 1935, the Chicago-based Indian Council Fire awarded him its third annual Indian Achievement Award. The first of these awards had been given to Sioux writer and physician Dr. Charles Eastman and the second was awarded to Pueblo potter María Martinez.

In 1935, Roe Cloud left the Haskell Institute to help facilitate the newly passed Indian Reorganization Act (IRA). His job was to persuade Indians across the country to vote for tribal reorganization under the IRA.

In 1936, Henry Roe Cloud was named Supervisor of Indian Education at the Bureau of Indian Affairs. One of his biographers, David Messer, writes:

“Despite the facts that he was only marginally responsible for supervising all of the educational work of the Indian Service and that the position sounded far more important than it was, his primary responsibility was to continue doing what he had been doing-trying to get the Indians to support the IRA.”

In 1939, the Indian Service (now called the Bureau of Indian Affairs) was facing budget cuts and Henry Roe Cloud was offered the superintendency of the Turtle Mountain Reservation in North Dakota. This was a demotion with a smaller salary and a lower Civil Service rank. After he complained to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, he was named Superintendent of the Umatilla Reservation in Oregon, a smaller reservation with a smaller salary.

Even though he was Indian, the reservation Indians were still leery of the Indian Service and they had rejected reorganization under the IRA. When the Umatilla General Council debated about hiring an attorney, he opposed this action. He told the Council that there was no need for an attorney as he could look up all of the answers to their legal questions in the federal code book. The council, however, still insisted that it wanted its own attorney.

As a result of the conflict over the attorney for the Umatilla, Roe Cloud was appointed Superintendent at the Grande Ronde-Siletz Agency on the Oregon coast. Shortly after his appointment, the agency was abolished and for the next two years he attempted to untangle the complicated genealogical records to see who was entitled to the money owed tribal members by the government.

He died of a heart attack in Siletz in 1950 at the age of 66.

Leave a Reply