In 1824, the Secretary of War, John C. Calhoun, established the Office of Indian Affairs without Congressional authorization. He did this by appointing Thomas L. McKenney to a vacant clerkship in the War Department and then directing that all matters relating to Indians be directed through this office. In 1832 Congress authorized the appointment of a Commissioner of Indian Affairs who was to be responsible for directing and managing Indian Affairs. The Commissioner was to report to the Secretary of War.

Commissioner of Indian Affairs

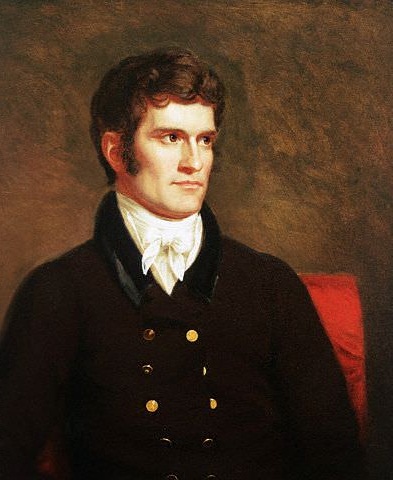

The Commissioner of Indian Affairs was appointed by the President and the primary qualification for the office was support for the President and his political party. The first Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Elbert Herring, was appointed by President Andrew Jackson. He was an ardent supporter of President Jackson’s Indian removal policies and did not feel that Indians had cultures which were worth preserving. In his first report to the Secretary of War, Herring claimed the despotic rule of the chiefs and lack of a sense of private property were keeping Indians in the savage life. He suggested that the educa¬tion of the youth and “the introduction of the doctrines of the Christian religion” could overcome this savage life.

In 1850, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs described the policy of “civilizing” Indians this way:

“When civilization and barbarism are brought into such relation that they cannot coexist together, it is right that the superiority of the former should be asserted and the latter compelled to give away. It is, therefore, no matter of regret or reproach that so large a portion of our territory has been wrested from its aboriginal inhabitants and made the happy abode of an enlightened and Christian people.”

For the most part, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs was more concerned with non-Indian interests on Indian lands than with the Indians themselves. This was particularly true when it came to mining. In 1872, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs wrote:

“It is the policy of the government to segregate such [mineral] lands from Indian reservations as far as may be consistent with the faith of the United States and throw them open to entry and settlement in order that the Indians may not be annoyed and distressed by the cupidity of the miners and settlers who in large numbers, in spite of the efforts of the government to the contrary, flock to such regions of the country on the first report of the gold discovery.”

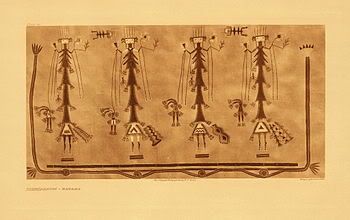

After Congress created the Smithsonian Institution in 1846 to fulfill the terms of the will of James Smithson, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs also became involved in obtaining materials for the museum. The Smithsonian was given custody of all federal government museum collections, including collections of Indian artifacts. The Smithsonian’s regents encouraged the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to collect items which would illustrate the history, manners, and customs of the Indians. Some of the items obtained for the museum came from graves which were robbed by Indian agents and others.

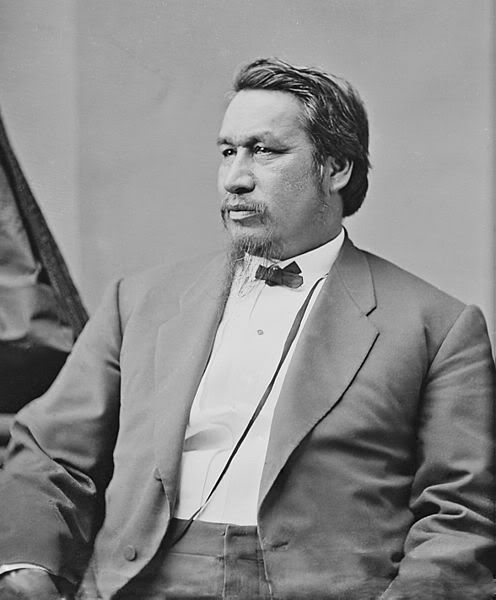

With the notable exception of Ely Parker (a Seneca appointed by President Ulysses S. Grant), the Commissioner of Indian Affairs had little understanding of or contact with Indian cultures. The Commissioner was aided in his duties by a cadre of clerks in Washington, D.C. The field force of the Office of Indian Affairs-superintendents and agents-were primarily political appointees and a few detached soldiers.

The Field Staff:

Since those in the field were political appointees, it was not uncommon for superintendents and Indian agents to have their very first contact with an actual Indian after arriving at their post. Very few came into the job with any real understanding of the history, culture, or reality of Indian life. Their primary qualification for appointment to the position was usually faithful party service.

Since the field staff knew that their positions were temporary-dependent on the outcome of the next election-they often misused the office for personal gain in wealth and/or politics.

Superintendents were responsible for Indians in a large geographic area. At times, this might be an entire Territory. The Indian superintendents were not only required to oversee the Indians under their jurisdiction, but also to supervise and to regulate any traders who conducted business with the Indians. It was not uncommon for the Indian superintendents to appoint the Indian agents and to select the sites for the agency’s headquarters.

Most Indian agents reported to a superintendent. Frequently the Indian agent was the only government representative actually residing with the Indians. Thus, the Indian agent occasionally engaged in the delicate tasks of diplomacy and negotiation to secure treaties with various tribes.

Indian agents, many of whom took the title of “major,” had dictatorial power on their reservation. They could have Indians arrested, whipped, and imprisoned; they could prohibit Indians from leaving the reservation; they could prohibit non-Indians from entering the reservation; they could require the Indians to attend church and to cut their hair. Within the reservation, the agent was the law and it was difficult, if not impossible, for the Indians to appeal to a higher authority.

Part of the agent’s responsibility included the distribution of annuities and supplies required to honor the treaties which had been ratified by Congress. The distribution of annuities and supplies was a profitable area for many Indian agents. They would simply open up a store in a nearby off-reservation community and stock it with supplies which the government had intended to be given to the Indians. The Indian agent might contract with some local non-Indian cattle growers to provide beef to the reservation. The weight of the cattle would be over reported and the agent would receive a “commission.”

The annuities promised to the tribes in treaties had to be shipped to the reservations. The Indian agent would often issue a shipping contract in which the actual number of miles was inflated and then receive a “commission” from the shipping company. In some instances, the agent was a silent partner in the shipping company.

The Indian agents were also responsible for “civilizing” the Indians. This usually involved government sponsored education and agricultural training programs which were based on federal policy goals, not the needs of the local tribes.

Another example of corruption can be seen in 1874 when the Commissioner of Indian Affairs persuaded President Ulysses S. Grant to restore the eastern portion of the Apache reservation in Arizona to the public domain by executive order. This portion of the reservation contained copper-bearing lands which non-Indians wished to mine. Both the Indian agent in Arizona and the Commissioner of Indian Affairs had financial holdings in the company which subsequently developed the copper mines.

Territorial governors often served as the ex-officio Superintendent of Indian Affairs for their territory. In this position, they reported to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, who, in the hierarchy of nineteenth century U.S. government, had little status. In this system, the territorial governor, in his role as Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the territory, was to report to the commissioner of Indian affairs, an inferior in the government’s hierarchy and protocol to the status of territorial governor. This also created some conflict of interest: as superintendent of Indian affairs, the territorial governor had a fiduciary responsibility with regard to the Indian tribes, while as territorial governor there was an obligation to encourage settlement, development, and, hopefully, statehood. Many, and probably most, of the territorial governors viewed Indians as an impediment to culture, civilization, and the economic exploitation of the land.

In 1864, Sidney Edgerton was appointed as Montana’s first territorial governor and ex-officio superintendent of Indian Affairs. With regard to his Indian policy, he said:

“I trust that the Government will, at an early day, take steps for the extinguishment of the Indian title in this territory, in order that our lands may be brought into market.”

In 1891, four groups of Indian Service employees – physicians, school superintendents and assistant superintendents, school-teachers, and matrons – were placed under Civil Service Classifi¬cations. This was the initial step for the creation of a professional field staff. School Superintendent Edwin Chalcraft explains:

“Prior to this time, Indian Agents made all those appointments, but from this date they were made by the Commissioner of Indian Affairs from names submitted to him by the Civil Service Committee in Washington, D.C. These rules prohibited the dismissal of employees for political or religious beliefs, but the Appointing Officer in Washington, D.C., could remove an employee for any other cause without giving him reason for doing so.”

In 1896, President Grover Cleveland issued an executive order which placed most Indian Service employees under Civil Service classifications. Only Indian agents and inspectors were exempt from Civil Service. Indians who applied for positions in the Indian Service were exempt from Civil Service requirements.

Leave a Reply