Following the Civil War, American politicians and influential citizens were acutely aware that there were major problems with the administration of U.S. policies regarding Indians. Congress appointed a special committee to investigate and debate a number of possible solutions.

In 1867, a special committee of Congress chaired by Wisconsin’s Senator James Doolittle reported that Indians outside of Indian Territory (now Oklahoma) were decreasing. With regard to Indian wars with non-Indians, the committee felt that most “are to be traced to the aggressions of lawless white men”. The committee report noted the loss of Indian hunting grounds and that driving the last vestige of the buffalo from the plains will “put an end to the wild man’s means of life”.

One of the major debates in Congress at this time focused on the Indian Office (now known as the Bureau of Indian Affairs). While the Indian Office was originally a part of the War Department, it had been moved to the Department of the Interior. At this time, there were many who felt that it should be moved back to the War Department as the Army was best equipped to deal with Indians. While commenting on the pros and cons of placing the Bureau of Indian Affairs in the War Department or leaving it in the Department of the Interior, the Doolittle Committee recommended that it stay in the Department of Interior.

Congress also debated whether Indian nations should be approached through negotiations or through the use of military force. In general, the view of using negotiations rather than force prevailed with proponents citing the huge cost of warfare with the Plains Indians. One Senator estimated the cost of killing an Indian at $1 million, while others felt that it would take 10,000 soldiers at least three years to “pacify” the Plains. The alternative to exterminating the Indians was to consolidate them on large reservations, out of the way of “progress” (and railroad lines), and then to “civilize” them.

President Andrew Johnson told Congress:

“If the savage resists, civilization, with the Ten Commandments in one hand and the sword in the other, demands his immediate extermination.”

After debating Indian policies, Congress authorized the creation of a Peace Commission composed of three generals and four civilians to negotiate settlements with the hostile Indians. The Peace Commission was to try to bring together the warring tribal leaders, to determine the causes of their unrest, and to negotiate treaties with them. Congress appointed the four civilian members of the commission and the President appointed the three army officers. All of the Congressional appointees were well-known opponents to the use of force against Indians. The army officers, on the other hand, were vociferous advocates of military force, stating that peace without punishment is impossible.

The charter given to the Indian Peace Commission was rather ambitious: it was to bring about a permanent peace with hostile tribes and the removal of all Indians to reservations located far from settlements, roads, and railroads. The Indians were to be persuaded to locate on reservations. Initially, these reservations were to be large enough to allow the Indians to continue to support themselves with hunting, but as they became more proficient as farmers, the size of the reservations was to be reduced. The government was also to provide the Indians with missionary instruction in Christianity. Non-Indians were to be excluded from the reservation, except for those employed by the government.

Outside of Congress, General Ulysses S. Grant asked General Ely Parker (a Seneca Indian) to develop a reform agenda for the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). Parker recommended the establishment and protection of land rights for Indian communities. To deal with the problem of corruption within the Indian service, he recommended that the BIA be transferred from the Department of the Interior to the Department of War. Parker felt that this move would shield the BIA from the influence of land and business interests. In addition, the government should provide money, goods, services, and new opportunities for Indian people in an effort to compensate them for dispossession of their land. Education, he felt, was particularly needed.

Ely Parker also suggested the creation of an oversight committee composed of private citizens. This committee would monitor the acquisition and distribution of goods and rations to the Indians. Parker felt that this oversight committee would instill confidence in Indian people and help ease tensions between them and local non-Indians.

Ely Parker also suggested the appointment of an Indian commission which would include educated Indians which would meet with every Indian community and advocate for general peace. Parker wanted this commission to

“assure the tribes that the white man does not want the Indian exterminated from the face of the earth, but will live with him as good neighbors, in peace and quiet.”

In 1868, the initial report of the Peace Commission on the reasons for Indian hostilities noted that the primary cause for war was injustice. In looking at the almost constant wars with Indians, the Commission then asked:

“Have we been uniformly unjust? We answer, unhesitatingly, yes!”

The report also condemned the cor¬ruption of the Indian Department and noted abundant cases in which

“agents have pocketed the funds appropriated by the government and driven the Indians to starvation.”

The Commission reported that while the United States had pledged to protect Indian nations against American depredations, it had failed to do so.

The Board of Indian Commissioners was created by Congress in 1869. The Board was to be made up of distinguished philanthropists who would serve without pay. The Board was to oversee the purchase and distribution of goods and supplies for the Indian Service (Bureau of Indian Affairs). The men who were appointed to the first Board of Indian Commissioners were wealthy businessmen, most of whom had served with the Christian Commission during the Civil War, and who were motivated, indeed driven, by a sincere Christian philanthropic zeal. None of the members of the Commission were Catholics. The Board developed a reform agenda that focused on confining Indians within increasingly smaller reservations and cultural assimilation by any means necessary. Most of the members of the Commission had no actual experience with Indian communities.

Almost all of the men who were appointed to this first Board had business interests in the dry goods, mineral extraction, and transportation industries. These were the industries that stood to benefit from Indian confinement in the West. Their business interests suggest that perhaps their personal interests influenced their Indian policy work and their support of coercive reservations.

The Board reported:

“The history of the government connections with the Indians is a shameful record of broken treaties and unfulfilled promises.”

The recommendations of the Commissioners included the abandonment of the treaty system and the abrogation of existing treaties. In addition, the “uncivilized” Indians should be seen as wards of the government with the duty of government to

“protect them, to educate them in industry, the arts of civilization, and the princi¬ples of Christianity”.

The Commissioners recommended the establishment of schools to introduce English to every tribe:

“The teachers employed should be nominated by some religious body having a mission nearest to the location of the school. The establishment of Christian missions should be encouraged, and their schools fostered.”

The report concluded:

“The religion of our blessed Savior is believed to be the most effective agent for the civilization of any people.”

William Welsh, the chairman of the Board of Indian Commissioners, published a book entitled Taopi and His Friends; or, the Indians’ Wrongs and Rights in which he laid out his ideas for Indian reform. He believed that treaties should not be made with Indian tribes and that the large reservations should be broken up. He had great faith in the process of Christianization. He believed that if Indians were to embrace Christian civilization, they had to be dispossessed and held coercively on reservations. If Indians would not go willingly to reservations, they should be forced to go or exterminated.

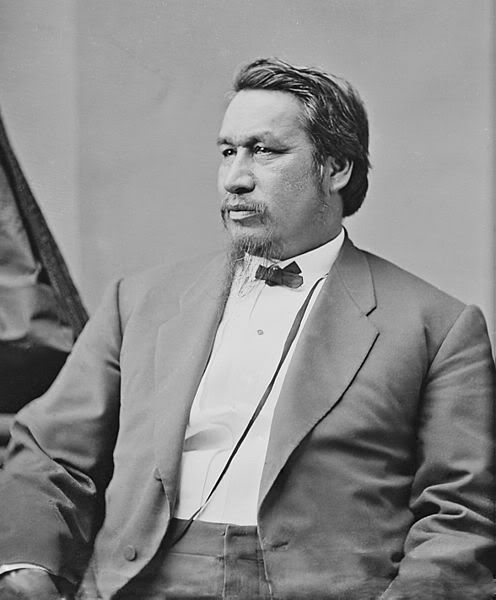

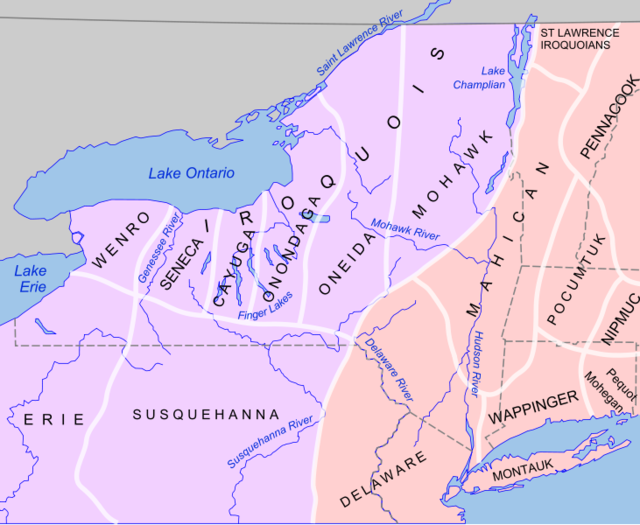

After Ulysses S. Grant became President, he appointed his friend Ely Parker as the first Indian to become Commissioner of Indian Affairs. Ely Parker had been born with the Seneca name Hasanoanda (Coming to the Front) on the Tonawanda Reservation. He was a member of the Wolf Clan and was the maternal great-great-grandson of the Seneca prophet Handsome Lake. He had served as clerk of his tribal council. The name “Parker” was the family name which his ancestors had adopted from an English captive and the name “Ely” was given to him by an Anglo teacher. He read law for three years, but was denied admission to the bar because, as a Seneca, he was not considered an American citizen.

Ely Parker is pictured above.

Since the end of the Civil War, Parker had served as Grant’s military adviser on Indian affairs. He had developed a policy agenda which held a notion that the federal government had a responsibility to compensate indigenous peoples for an economic and political system of domination that had dispossessed them of land, resources, opportunities, and political autonomy.

Ely Parker did not view Indian tribes as sovereign nations. In his annual report as the Commissioner of Indian Affairs he stated:

“The Indian tribes of the United States are not sovereign nations, capable of making treaties, as none of them have an organized government of such inherent strength as would secure a faithful obedience of its people in the observance of compacts of this character.”

Parker also wrote:

“…great injury has been done to the government in deluding this people into the belief of their being independent sovereignties, while they were at the same time recognized only as its dependents and wards.”

Parker believed Native people would assimilate into mainstream culture and society on their own terms and in their own time frame. His experience in dealing with corporations, such as land companies, showed him that when corporations influenced public policy, the Indian people faced injustice, dishonesty, greed, and dispossession.

Parker’s term as Commissioner of Indian Affairs was relatively brief. In 1871, he was investigated by the House of Representatives Committee on Appropriations on charges that he had defrauded the federal government. While the Committee found much to condemn, it found no evidence implicating him in any wrong-doing. Under this cloud of criticism he resigned.

The Board of Indian Commissioners continued to be a major force in influencing Indian policies for several decades. During this time, the government sought to destroy the Indian tribes by breaking up the reservations and to destroy Indian cultures by removing children from their homes at an early age so that they could be raised outside of their tribal cultures. As a result of these policies, Indian wealth in the form of land and natural resources was transferred to non-Indians and American Indians became the poorest group in the United States, a distinction which they continue to hold.

Leave a Reply