Almost since the foundation of the United States, the westward expansion of the country was guided by Manifest Destiny, the idea that it was the country’s destiny to span the continent from the Atlantic to the Pacific. By the middle of the nineteenth century, it was clearly evident that the way of westward expansion would have to involve railroads which could then transport raw materials (minerals, timber, cattle, grain) from the west to the east and manufactured goods from the east to the west.

It was not unfettered capitalism that drove the railroads across the Great Plains to the Pacific Ocean, but capitalism nurtured and supported by the federal government. In 1853, the United States War Department dispatched five separate survey parties to map out the most economical and practical railroad routes. In 1854, Washington Territorial Governor Isaac Stevens set out to impose treaties on the Indian nations of what is now Washington, Idaho, and Montana which would move Indians out of the way of the railroads and the non-Indian settlers that the railroads would bring in.

In 1864, legislation authorizing the Northern Pacific Railroad was signed by President Lincoln. There was little concern for the fact that it would be crossing Indian lands.

In 1871, the Indian Superintendent for Montana invited Sioux leaders Sitting Bull and Black Moon to a peace conference at Fort Peck. The Americans wanted to talk with the Sioux about the proposed Northern Pacific Railroad which would cut through their lands. The two chiefs maintained their hard line stressing no American invasion of their lands.

In 1871, a survey party laid out a route for the Northern Pacific Railroad in the unceded lands near the Yellowstone River. A war party of Sioux, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapaho with 400 to 1,000 warriors found the survey party’s camp and attacked. Some Sioux warriors slipped past the camp’s guards and captured six army mules which were tied near the commander’s tent. They also liberated some saddles.

From the bluffs above the camp, the Indian warriors fired into the camp. Some warriors, including Crazy Horse, attacked the camp by riding around it in circles. After a few hours, Sitting Bull called for an end to the battle. Crazy Horse made one last charge and had his horse shot out from under him.

William Welsh, the former chairman of the Board of Indian Commissioners, supported the creation of the Northern Pacific Railroad in 1872 as it would

“bring the lawless Indians of the North into subjection, and thus aid effectively the religious bodies charged with bringing Christian civilization.”

In 1872, 150 Sans Arc Sioux lodges under the leadership of Spotted Eagle arrived at the Cheyenne River Agency. Spotted Eagle told Colonel David Stanley that the Sioux had not given their permission to build a railroad through their territory. He warned the Americans that if they insisted on building the railroad that the Sioux would kill the builders and tear up the tracks. The threat had little impact on the government backing for the Northern Pacific Railroad.

In North Dakota and Montana, surveyors were sent out from Fort Rice and from Fort Ellis under military escort to survey the placement of the Northern Pacific Railroad through the Yellowstone country. This was a direct affront to the Sioux and their allies.

In Montana, about 2,000 Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho gathered at the big bend of the Powder River for a traditional Sun Dance. Following the Sun Dance they launched a major raid against the Crow to capture Crow horses. More than 1,000 warriors began their invasion of Crow territory when they discovered a Northern Pacific Railroad survey party. The survey party of 20 men was protected by about 500 soldiers under the command of Major Baker. The Americans were camped at Arrow Creek (now called Pryor Creek) near present-day Billings.

A group of young warriors attacked the sleeping American camp, scattering the army livestock. The following day, a larger force under Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse took a position on the bluffs above the Americans’ well-fortified site. Some of the warriors fired down at the soldiers and engineers. Sitting Bull walked down from the promontory and sat down within firing distance of the soldiers. There he opened his pipe bag, loaded the pipe with tobacco, and smoked it with the four warriors who had accompanied him. With bullets kicking up dust around them, Sitting Bull calmly and serenely smoked the pipe and passed it to the others. Historian Robert Larson, in his biography Gall: Lakota War Chief, writes:

“After each man had taken his puff, Sitting Bull, wearing only two simple feathers and carrying his bow, quiver of arrows, and gun, carefully cleaned out the bowl of the pipe. He then got up and slowly led his anxious comrades back to the main Indian lines.”

The Battle of Arrow Creek (also called the Baker Battle) was more of a skirmish than a battle and there were few casualties. The leader of the surveyors, however, insisted on returning to Fort Ellis and refused to work in the Yellowstone area. This caused the survey efforts to move north to the Musselshell River. In an article in North Dakota History, Robert Larson puts in this way:

“This assault terrified the surveyors under Baker’s protection; these nervous civilians decided to redirect their efforts forty miles northward to the Musselshell River, a possible optional route for their proposed northern transcontinental route.”

In Montana, a small party of 20 to 30 Sioux warriors under the leadership of Gall encountered the Northern Pacific survey party from Fort Buford near the confluence of the Powder and Yellowstone Rivers. Gall’s warriors surprised the sleeping American camp before dawn, but failed to stampede their livestock. The Americans managed to retreat to the west bank of the Powder River.

Gall walked down to the riverbed opposite from the Americans. He placed his rifle on the ground and asked to speak to the leader of the trespassers. Colonel Stanley laid down his pistol and walked to the opposite bank. He asked Gall to meet him on a sandbar in the middle of the river, but Gall refused. Stanley then broke off the talks and there was an immediate exchange of gunfire.

At this point, Sitting Bull arrived with a large war party. However, the Americans were equipped with Gatling guns and easily drove the Sioux warriors back. The Sioux, however, followed the Americans, picking off occasional stragglers.

In 1873, the Northern Pacific Railroad’s military escort under the command of Lt. Col. George A. Custer was attacked by about 350 Sioux and Northern Cheyenne under the leadership of Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse. The Sioux were poorly armed and inflicted few casualties on the army.

Custer organized a charge that scattered the attacking Indians. In her book Montana Battlefields 1806-1877: Native Americans and the U.S. Army at War, Barbara Fifer reports:

“Winning this skirmish gave the colonel a deep, and ultimately deadly, belief that the Sioux and Cheyennes were ‘cowardly’ and one good charge was all it took to beat them.”

Using the skills of Arikara scout Bloody Knife, Custer’s troops tracked the war party to the mouth of the Bighorn River. Here warriors under the leadership of Crazy Horse again attacked and again Custer charged and drove them back.

In spite of attacks by the Sioux and their allies, the Northern Pacific Railroad reached the Yellowstone River at Miles City, Montana in 1881. This allowed for the direct shipment of buffalo hides to the east and increased commercial buffalo hunting. In 1884, the Northern Pacific sent its last carload of buffalo hides to the east. The once great herds were now nearly extinct.

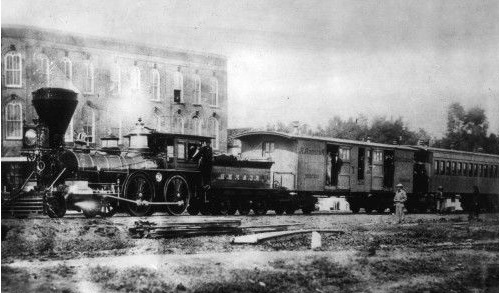

In 1883, the last spike of the Northern Pacific Railroad was driven at Independence (now Gold) Creek in Montana marking the completion of the first of the northern transcontinental railroads.

Leave a Reply