Fifty years ago, in 1961, winds of political and social change were sweeping across the United States. There was not only a new President, John F. Kennedy, but there were new concerns and awareness of civil rights for American minorities, including American Indians. During the 1950s, government policies toward Indians had emphasized total assimilation and the termination of tribes. With the election of Kennedy, there was now a renewed optimism among Indians.

Inaugural Parade

In Washington, D.C., the inaugural parade for President John F. Kennedy included five American Indian entries. Kennedy had pledged to end the termination policies which had characterized the 1950s and had promised a more vigorous domestic Indian policy. This gave Native Americans across the country renewed hope.

The float by the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI) was entitled “First New Frontier-1620” and symbolized the hospitality that Indians extended to the first Europeans. The Montana tribes organized an entry called “Sacajawea and Lewis and Clark Blaze Montana’s New Frontier” which evoked images of peace and cooperation in a new era. Members of the Rosebud Sioux tribe entered a group on horseback in traditional Indian regalia. The group, however, was behind the Marine band. When the band’s drums started, they startled the horses and Bob Burnette who was leading the group was thrown from his horse. The horse got away and Burnette finished the parade in the back of a Marine jeep.

Land Sales Policy

The Department of the Interior changed federal land sales policies to give Indian tribes the first opportunity to buy land offered for sale by individual Indians. This was a partial reversal of the Termination Policy.

Symposium

A symposium on “Declaration of Indian Purpose” was held at the University of Chicago and was attended by nearly 500 Indians from 65 tribes. The Indian participant asked for Indian involve¬ment at all levels of government. According to the Declaration:

“What we ask of America is not charity, not paternalism, even when benevolent. We ask only that the nature of our situation be recognized and made the basis of policy and action.”

Indian participants in the symposium included representatives from groups without federal recognition. The gathering also included off-reservation Indians.

The Declaration of Indian Purpose declared:

“We, the Indian people must be governed by principles in a democratic manner with a right to choose our way of life. Since our Indian culture is threatened by the presumption of being absorbed by the American society we believe we have the responsibility of preserving our precious heritage.”

The document was written by D’Arcy McNickle, a Flathead novelist and employee of the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

While the conference had broad participation, there was some opposition to it. The Montana Inter-Policy Board urged Montana tribes to boycott the event because of the involvement of the National Congress of American Indians. There were also some who opposed the participation of anthropologists such as Sol Tax in the event.

National Indian Youth Council

In New Mexico, the National Indian Youth Council (NIYC) was founded by Vine Deloria and others. NIYC was impatient with the slow pace of change and the methods of the National Congress of American Indians.

Melvin D. Thom (Paiute) was selected as president and Herb Blatchford (Navajo) was executive director. Leonard Crow Dog would later write:

“This was a forerunner of AIM and a big step for Native American rights”

NIYC was strongly influenced by the civil rights movement. They focused on self-determination and Indian sovereignty. Their goal was a world in which Indians would be able to make decisions for themselves.

Yellowstone National Park

In Wyoming and Montana, Yellowstone National Park issued the following statement:

“The National Park Service now believes that the Yellowstone Park Area may not have been taboo to the nomadic Indian tribes which frequented the Northwest in prehistoric times. Evidence collected over the past several years seems to indicate that many tribes have been more or less permanent residents of this geologically mysterious area.”

Urban Indian Centers

In Oakland, California, the Quakers established the Intertribal Friendship House. This inspired Adam Nordwall (Red Lake Chippewa) and others to organize the United Bay Area Council of American Indian Affairs (usually called the United Council). Most of the membership of the United Council was made up of existing social clubs, including the Navajo Club, the Haida Tlinget Club, the Haskell Alumni, and the Four Winds Club. These groups offered fellowship and traditional singing and dancing, and a chance to speak one’s tribal language.

In Chicago, Illinois, St. Augustine’s Center for American Indians was established by Father John Powell, a parish priest at St. Timothy’s Episcopal Church. Powell emphasized the parallels between Native religions and Christianity. While the Center was open to Indians from all tribes, it tended to appeal to those who had already encountered Episcopal missionaries and churches.

Land Claims

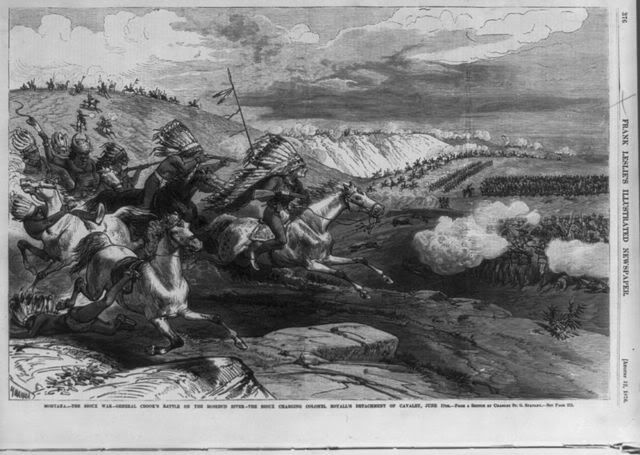

The Indian Claims Commission ruled that the Northern Cheyenne, Southern Cheyenne, Northern Arapaho, and Southern Arapaho had not been paid full value for the lands in Colorado, southwestern Wyoming, western Kansas, and Nebraska which they had ceded to the United States under the 1851 Treaty of Fort Laramie. All parties agreed that the value of these lands should be determined as of October 14, 1865.

The Cherokee were awarded $15 million by the Indian Claims Commission for the Cherokee Outlet lands in Oklahoma.

The Indian Claims Commission denied the Cherokee Freedmen’s Association claim to tribal citizenship. The commission felt that the claims were individual in nature and therefore the commission had no jurisdiction.

Termination

In Wisconsin, termination of the Menominee was finalized and the reservation became a county. The Menominee Enterprises Inc. (MEI) now administered all tribal assets, including land, forest, and the sawmill. Each of the 3,270 tribal members received a receipt for 100 shares of common stock in MEI. The actual shares were issued to the corporation’s Voting Trust, which was empowered to elect the MEI Board of Directors.

The First Wisconsin Trust Co. of Milwaukee was assigned guardian powers to act as a trustee for all tribal minors and incompetents. Tribal members could be determined to be incompetent by the Secretary of the Interior without any judicial hearings and legal process.

States and Indians

Connecticut defined “Indian” as a person with one-eighth Indian blood from a tribe whose reservation was set aside (that is, established by the European and/or American authorities). The state defined several reservations: Eastern Pequot, Golden Hill, Schaghticoke, and Western Pequot (Mashuntucket Pequot). The state welfare commissioner was responsible for caring for reservation residents and maintaining land and buildings. Connecticut defined “tribal funds” as those held in trust by the state for the Indians and benefit of a tribe.

California created the State Advisory Commission on Indian Affairs as the successor to the Senate Interim Committee on Indian Affairs. The Commission was to investigate and make recommendations concerning the termination of Indian reservations and federal Indian services. All of the Commission members were non-Indians.

In South Dakota, lobbyists for the non-Indian Taxpayers League drafted a bill which was introduced in the state House of Representatives which assumed state jurisdiction over all criminal and civil matters in Indian country under the provisions of Public Law 280. The primary concern of the Taxpayers League was “lawlessness”, especially drunken driving on the highway. Enforcing the proposed law, however, would entail increased costs to the state so the bill was amended to assume jurisdiction only over actions on the highways through Indian country. The bill passed and became law.

Museums and Archaeology

In Arizona, the Navajo established a tribal museum and a research program. The research program was used for researching Navajo pre-conquest land claims before the Indian Claims Commission.

In Wyoming, the Bradford Brinton Memorial & Museum was established near Big Horn. One room in the museum was dedicated to American Indian objects. The museum’s Indian collection included about 250 pieces from throughout North America.

In Idaho, a leveling operation uncovers a group of 29 stone artifacts, including 5 large Clovis points. Archaeologists usually date the Clovis culture to about 12,000 years ago. The find appears to have been a cache that had been intentionally buried by people who planned to later recover it.

In-Lieu Fishing Sites

In Oregon, the Umatilla Tribes’ Fish Committee report reflected frustration at the federal government’s avoidance of carrying out its promises to provide in-lieu fishing sites to replace those lost through Bonneville Dam. In-lieu fishing sites were very important to the tribe.

Recognition Request

In Texas, the mayor of El Paso wrote to the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) voicing the opinion that the Tigua should have the same rights, privileges, and protections as other American Indian tribes. In response to this letter, the BIA points out that with one exception (the Alabama-Coushatta) the federal government had never assumed responsibility for any Indian tribe in Texas. According to the BIA, Texas entered the Union as a fully self-governing state and thus there were no public domain lands nor any trust responsibility for any tribes living upon them. Alan Minter, the Assistant Attorney General of Texas, wrote:

“When Texas became a state in 1845, it was the beginning of the end for the Indian.”

Leave a Reply