The Great Plains is a huge American Indian culture area which is generally sub-divided into the Northern, Central, and Southern Plains. Among the Indian nations of the Central and Southern Plains, the customs regarding names-their use as well as the naming process-varied greatly among the different cultures.

Central Plains

The Central Plains lie south of the South Dakota-Nebraska border and north of the Arkansas River. It includes Nebraska, Iowa, Kansas, Missouri, southeastern Wyoming, and western Colorado. At the time when the Europeans began their invasion of this area it was the home to Indian nations such as the Ponca, Omaha, Osage, Otoe, Quapaw, Iowa, Missouria, Kansa (also known as Kaw), Pawnee, Wichita, Arapaho, Cheyenne, Yankton Sioux, and the Teton Sioux.

Among the Otoe and Missouria, the child was given a name on the fourth day after birth to insure a long and successful life. Each name included a song which became the property of the owner (the person who now carried the name). The naming ceremony was the initiation of the child into the clan. As an adult, an individual might take on a new name based on a vision or on some deed.

Otoe and Missouria children were also given nicknames by the mother’s brother. The nicknames, considered to be lucky names, were usually obscene and uncomplimentary and were intended to keep people from talking unkindly about others.

Among the Kansa, the child was given a name shortly after birth. The name reflected both clan affiliation and birth order and was given in a ceremony conducted by a tattooed warrior. Additional names might be assumed later in life and these names would usually refer to a deed of valor.

Among the Osage, personal names were owned by the clan and these names reflected the spiritual associations of the clan. The naming of a child was an important ritual as it conferred upon the child both clan and tribal membership.

The Omaha felt that personal names were on loan for the lifetime of the bearer. Upon the death of the bearer, the name would revert to the “name pool” and could be reassigned to a younger tribal member. At the fourth day of life, the child was given a “baby name” which was retained for the first 3-4 years of life. The “baby name” was then thrown away during the Turning The Child Ceremony in which the child received new moccasins and a clan name.

Omaha men frequently changed names during their lives and so it was possible for two men to share the same name at different times in their lives. It was not uncommon for a warrior to assume a new name after a successful war party. These “bravery” or “valor” names established a claim on public esteem.

The number of names available for Omaha women was relatively small and consequently there were many Omaha women with the same name. In addition, women’s names were not generally linked to clans and thus women in different clans could share the same name.

Like many other tribes, Omaha etiquette did not allow an individual to be addressed by a personal name. Under no circumstances was it polite to ask a stranger’s name.

The Pawnee never addressed each other by personal name, but by a kinship term. This kinship term indicated the expected behavior and reinforced the relationships between people. A personal name was an honorary title of an extremely personal nature. The substance of the personal name was strictly private and reserved to oneself. The name was cited only on the most formal occasions and from the name itself it was not possible to deduce its private significance.

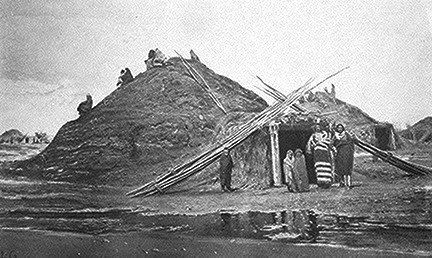

A Pawnee lodge is shown above.

Among the Wichita, children were sometimes named before birth because of the dreams of the mother or another relative. In some instances, a number of warriors would be invited into the father’s lodge and their names pronounced. The child would then select one. The child would then be given not the warrior’s name, but rather a name referring to an act of valor performed by that warrior. Among high status families, boys and girls might change their names as teenagers.

Southern Plains

The Southern Plains lie south of the Arkansas River valley. It includes Oklahoma, Arkansas, portions of Texas, the eastern foothills of New Mexico, and portions of Louisiana. At the time of first European contact, this area included hunting and gathering tribes, such as the Comanche and the Lipan Apache, and more agricultural tribes such as the Caddo.

Among the Comanche, children were called by nicknames. Later they would be given a formal name or real name at a public naming ceremony. There was no set time for giving real names and names were not distinctive of gender. The naming ceremony began with a pipe ceremony and then the child would be lifted up four times and given a name. A sickly child would often be given a strong name to make the child strong.

Comanche girls were named after their mother’s relatives. Later in life, a woman’s name would not indicate whether she was married or single.

Among the Kiowa and the Kiowa-Apache, children were named shortly after birth by a grandparent or some other relative. Names usually referred to some incident or to a great deed by an ancestor. Later in life, new names could be adopted as the result of a vision or because of warfare or hunting.

Caddo children were traditionally named six to eight days after birth. This first name was usually a diminutive of the name of the parents. The naming ceremony was done by an elder who held the child, bathed it, and then would ask the parents what name they would like to give it.

Among the Southern Plains tribes there were also some customs with regard to the names of the dead. Among the Comanche, the name of a dead person was not spoken for several years. Among the Tonkawa, the name of a dead person and names similar to those of a dead person were never spoken. Out of respect for the deceased’s family, the Kiowa never spoke the name of the dead.

Leave a Reply