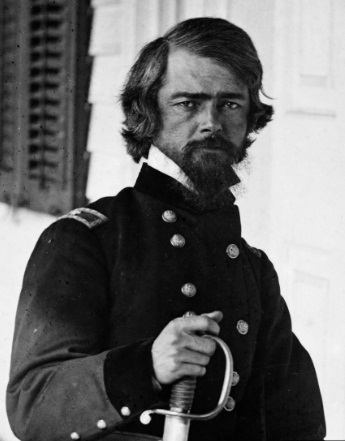

In 1855, Washington Territorial governor Isaac Stevens set out to prepare the territory for an influx of American settlers. In order to make way for these settlers, the American government had to obtain title to the land from the Indian Nations who owned it and to move the tribes out of the way of the settlers and the railroad that would open up the territory.

The American negotiators met with tribal leaders near present-day Walla Walla. Governor Stevens brought with him the plans to establish two reservations: one reservation was to be located in Nez Perce country for the Nez Perce, Cayuse, Walla Walla, Umatilla, and Spokan; the other reservation was to be in Yakama country for the Yakama, Palouse, Klikatat, Wenatchee, Okanagan, and Colville. The rest of the area could then be purchased by the government and a railroad built through the area. The lands which Stevens had selected for the reservations were those which the American settlers would not want, lands which offered little agricultural potential, and which were out of the way of the railroad.

Stevens quickly found out that most of the tribal leaders disliked his proposal, so he then proposed a scheme with three reservations. The third reservation was to be in Umatilla country for Umatilla, Cayuse, and Walla Walla.

Upon arriving at the treaty council, the Nez Perce put on a show of horsemanship and dancing. Governor Stevens and the other Americans failed to recognize the significance of the Nez Perce entrance. According to the Nez Perce Tribe:

“Our Nez Perce ancestors were not only honoring him as an important person: they were also demonstrating that the Nez Perce are a strong and important people who expect to be treated as equals.”

Stevens told the Indian leaders that there were some “bad” Americans who made trouble for the Indians, but east of the mountains the Great Father had taken measures to help his “Indian children” by moving them across a great river where they were away from the “bad” Americans. He carefully omitted any mention of the coercion, starvation, death, and misery that accompanied the Indian removal which the Cherokee called the Trail of Tears. The Americans were apparently unaware that the Indians of the Plateau had been told the story of the Trail of Tears for years by the Iroquois, the Delaware, and the Plains Indians. Delaware Jim, for example, had lived with the Nez Perce for many years and gave them a different account of the removal of the eastern Indians.

Stevens told that Indians:

“We want you and ourselves to agree upon tracts of land where you will live; in those tracts of land we want each man who will work to have his own land, his own horses, his own cattle, and his own home for himself and his children.”

The Indian leaders were not in agreement about the American proposals. They are angered by the arrogant and haughty manner in which the proposals were presented. Peopeo Moxmox, one of the Walla Walla leaders, told the Americans:

“You have spoken in a manner partly tending to evil. Speak plain to us.”

Cayuse chief Howlish Wompoon told the Americans:

“Your words since you came here have been crooked.”

The Nez Perce leader Lawyer told his people that the agreement with the Americans would protect their villages from the Americans and that without it, the Americans would simply take their lands.

Joseph pleaded for the inclusion of his peoples’ Wallowa valley in the Nez Perce reservation. Joseph, leader of the Wallamwatkin band, did not sign the treaty, saying that no one owned the earth and that one could not sell what one did not own. The American government, on the other hand, proceeded with the convenient legal fiction that the Nez Perce band, because they all spoke the same language, must be a single political entity with tribal leaders recognized by the United States who could represent the tribe as a whole. Writing in 1878, Duncan McDonald put it this way:

“Not being able to gain to his aim the consent of any of the real chiefs, Governor Stevens, a man of much ability and few scruples, cut the Gordian knot for the government by providing a chief freshly manufactured for the occasion.”

The man chosen by the United States to be the supreme chief of the Nez Perce was Lawyer, who was regarded by the Nez Perce as a tobacco cutter (a sort of undersecretary for Looking Glass, Eagle of the Light, Joseph, and Red Owl). Duncan McDonald, who was Eagle of the Light’s nephew, put it this way:

“In other words, for certain considerations he was prevailed upon to sign away the rights of his brethren-rights over which he had not the slightest authority-and although he was a man of no influence with his tribe, the government, as if duty bound on account of his great services, conferred upon him the title and granted him the emoluments of head chief of the Nez Perces.”

Many of the Nez Perce, particularly those who were not Christian, strongly felt that Lawyer did not have the right, or the ability, to speak on their behalf, let alone sign an agreement which would bind them to anything.

One of the interpreters for the treaty conference later reported that Governor Stevens ran out of patience with the negotiations and tells the Indians:

“If you do not accept the terms offered and sign this paper (holding up the paper) you will walk in blood knee deep.”

Stevens made many grand promises to the Indians during the treaty negotiations, most of which were not included in the actual treaties. For example, Stevens promised the Indians that they would not have to move onto the reservations until one year after the treaty was ratified by the Senate. However, the treaty contained a clause that guaranteed

“the right to all citizens of the United States to enter upon and occupy as settlers any lands not actually occupied and cultivated by said Indians at this time, and not included in the reservation.”

As soon as the treaties were signed, however, Stevens informed the newspapers that the lands were now open for immediate settlement.

The Americans had come to the treaty conference with a prepared treaty which they had intended to impose upon the Indian nations. The treaty commissioners displayed remarkable ignorance or disregard of tribal political structures. They arrogantly lumped fourteen distinct tribes into one nation under the name ‘Yakama’ and declared Kamiakin as its head chief. The treaty declared that the Yakama, Palouse, Pisquouse, Wenatshapam, Klikitat, Klinquit, Kow-was-say-ee, Li-ay-was, Skin-pah, Wash-ham, Shyiks, Ochechotes, Kah-milt-pah, and Se-ap-cat were to be considered as one nation. Many of the Columbia River tribes had not been present at the council. While Stevens claimed that Kamiakin had signed the treaty on behalf of the fourteen tribes, Kamiakin claimed that he only made a mark of friendship for himself.

While the Palouse knew that the treaty council was being held at Walla Walla, they made a conscious choice not to attend. From an Indian viewpoint, if they do not attend the council and participate in the discussions, they would not be bound by any decisions that are made. Unfortunately, the American government did not hold the same view.

Three Palouse chiefs-Kahlotus, Slyotze, and Tilcoax-attended the council in an unofficial capacity and played no role in the official meetings. They observed and spoke with leaders from other tribes.

Twelve days after the treaties were signed at Walla Walla, the newspapers in Washington and Oregon announced that the land east of the Cascade Mountains was now open for American settlement. The announcement, made with the approval of Governor Stevens, ignored the fact that the treaties had to be ratified by the Senate and proclaimed by the President before they could be legally binding and that the Indians had been promised that there would be no American settlement for two or three years. This set the stage for the wars which would sweep across eastern Washington for the next few years.

Leave a Reply