Southeastern Agriculture

When the Spanish first arrived in what is now the Southeastern United States, they found Indian nations that had been agriculturalists for more than a thousand years. In 1539, the Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto landed in Tampa Bay (Florida) with a large force and began marching north. The Spanish report that they passed by many great fields of corn, beans, squash, and other plants. In one instance they reported that the fields ran for two leagues (approximately 4-5 miles) and that they spread out for as far as the eye could see on either side of the roadway. It is estimated that this represented more than 10,000 acres under cultivation.

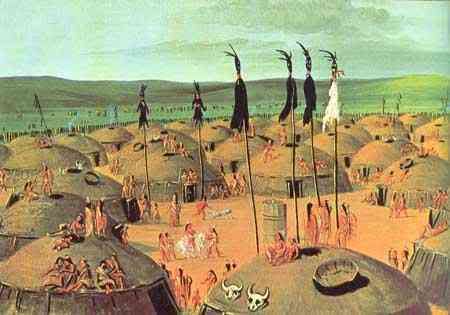

Crops (primarily corn, beans, squash, and tobacco) were planted along the creeks and bottomlands near the villages. The area would be first cleared by cutting and burning. The ashes of the burnt wood and cane would then nourish the crops. In addition to the primary crops, the Indians of the Southeast also raised sunflowers, pumpkins, sumpweed, chenopodium, pigweed, knotweed, giant ragweed, canary grass, amaranth, and melons.

In order to obtain a maximum yield from their fields, the Southeastern Indians practiced both intercropping and multiple cropping. Intercropping involved planting several different kinds of plants together in the same field. By planting corn and beans together, for example, the bean vines could twine themselves around the corn stocks.

One interesting aspect to intercropping was the practice of leaving and/or planting trees in cultivated fields that yielded nuts and fruits. This practice helped maintain long-term soil fertility. These trees included cherries, white and red mulberries, persimmons, walnuts, chestnuts, plums, and dwarf chinquapins. In addition to helping provide nutrients, the trees also attracted birds. The birds, in turned, helped to restrain the insect population in the fields.

Multiple cropping involves the planting of two successive crops in the same field. Thus, early corn was planted first. It ripened early and was picked green. Then the field would be cleared and a second crop was planted. However, double-cropping drains soil fertility unless there was some method of restoring nutrients to the soil. It is evident from both historical accounts and from the archaeological record that the Southeastern nations retained their fields for long periods of time and therefore must have replenished soil fertility.

The farming practices of the Southeastern Indians did not rapidly exhaust the soil. They planted beans with corn, thus offsetting the latter’s great consumption of nitrogen. They also carefully hoed the fields to avoid eroding the land. Among the Yamasee, who planted their fields near lagoons and marshes, the cultivated areas were regularly rotated to avoid soil exhaustion.

There is another important reason for raising both corn and beans. While corn supplies some essential protein, it lacks the amino acid lysine. On the other hand, lysine is abundant in beans. Thus, when beans and corn are eaten together they are a good source of vegetable protein.

As a fresh vegetable, squash was often used in stews. It was also sun dried, which concentrates the sugar so that dried squash could be cooked as a sweet dish.

A number of tribes in Florida, including the Timucua and the Calusa, cultivated a tuber known as Zamia. The Zamia plant appears to have been introduced into Florida by the ancestors of the historic Calusa from a source area in the Caribbean islands.

Not all cultivated plants were food plants. The Southeastern Indians also grew bottle gourd (Lagenaria siceraria). When cured, the bottle gourd has a hard shell that is very light and difficult to break. Bottle gourds were used for making water vessels, dippers, ladles, bowls, cups, rattles, masks, and bird houses. Tobacco was also grown.

Unlike the Europeans, the Indians of the Southeastern Woodlands did not view land as private property. Land was held in common with individuals and families having use rights. These farming rights were held as long as they continued to use the land. Use rights were generally respected and an individual or family would not seek access to a piece of land until it had been abandoned.

Among the Creeks, the amount of land under cultivation at each town would be increased whenever a child was born. To determine the amount of land needed by the town, a census would be taken each year.

The fields were worked communally. The entire field was not tilled, but rather worked into small hills about a foot in diameter which were spaced about three feet apart and which were laid out in straight lines. This method of preparation prevented soil erosion and preserved the fertility of the soil longer than did the plow-agriculture introduced by the later European colonists.

Among the Seminole, everyone in the village helped keep the crops healthy until they could be harvested. During the day, the children and the older people would drive away the nuisance birds. At night, the men would patrol the fields to keep the nocturnal animals away. Deer, bear, and raccoon were fond of Seminole crops.

The Cherokee built large scaffolds in their fields so that they could watch for crows and raccoons. During the summer, elderly women would sit on the scaffolds watching the fields. They would attempt to scare away animals which might eat the crops.

Fields were cultivated with handled implements that the first Europeans described as hoes. These implements had blades of stone, oyster, mussel shell, fishbone, or wood. In addition, they used a digging stick for making holes into which the seeds were planted.

An important part of agriculture is the ability to store the harvested crops in such a way that they are kept safe from mice and other animals. To do this, the Southeastern Indians built corn cribs which were raised 7-8 feet on posts. The posts were polished so that the mice could not climb them. The crib itself was plastered and the door was sealed. When corn was taken from the crib, the seal would be broken, the door opened, some of the corn removed, and then the closed door was resealed to protect the corn which remained in the crib.

The early European settlers were amazed at the number of different ways that the Indians prepared corn. It is estimated that there were at least 42 different ways of preparing corn, each with its own name. Corn was processed into hominy which has been described as the staff of life for the Southeastern Indians. This process involved the use of wood-ash lye which selectively enhanced the nutritional value of the corn by increasing amino acid lysine and niacin. This protects people who eat a corn-based diet against pellagra.

To produce the wood-ash, the Choctaw women would pour cold water over clean wood ashes placed in a hopper. This would produce a yellow lye which would drip down into a small container. This lye would then be added to the cornmeal.

Among the Choctaw, corn was made into paluska holbi, which was a kind of bread. Boiling water would be poured into cornmeal, which was then pounded into a stiff dough, and shaped into small rolls. These rolls were then wrapped in corn husks and cooked under hot ashes. For a richer taste, they would add chestnut or hickory oil to the cornmeal.

Another Choctaw cornbread was bunaha. This was prepared by mixing dried beans, wild potatoes, and/or hickory with the cornmeal. The rolls of this mixture, wrapped in cornhusks, were then boiled in water.

As with tribes in other parts of North America, the tribes of the Southeast raised and gathered tobacco which was used for smoking. Among the Choctaw, tobacco was mixed with the leaves of other plants when used for smoking.

Many of the tribes also cultivated plums, particularly the Chickasaw plum (Prunus chicàsa). Later Europeans described this as a wild plant and failed to notice that it was found only near abandoned Indian fields.