Southeastern Indian Hunting

While the Indian nations of the American Southeast were an agricultural people, they used hunting to supplement their diet. Just as these nations held their agricultural lands in common, so too were hunting territories held in common. While agricultural lands were assigned to clans or family lineages, there was no assignment of use rights for hunting lands.

In general, the most important animal in the Southeast was the deer whose flesh was used as food; its skin was used for clothing; its horns were made into arrow points; its hooves were made into rattles; its sinews used for sewing and binding; and its bones were fashioned into a variety of articles. A typical Creek family, for example, needed about 25-30 deerskins per year. The white-tailed deer provided 50 to 90 percent of the protein eaten.

Hunters would range as far as 300 miles from their towns while hunting for deer. While these extended hunts were conducted by men, they were accompanied by women and by some children. These hunts were usually conducted in the winter – beginning in November or December and ending in February or March.

During the rutting season – September through November – deer would be hunted using a technique in which a deer-head decoy was used to attract bucks into range. There were, however, two drawbacks to this technique: (1) rutting bucks are very aggressive and sometimes would attack the hunters, and (2) the decoys were so realistic that hunters were sometimes accidentally shot by other hunters.

Communal hunts, which could involve as many as 300 hunters, would use a fire surround to force the deer into a small area where they could be easily shot. In using this technique, an area up to five miles in circumference would be set on fire.

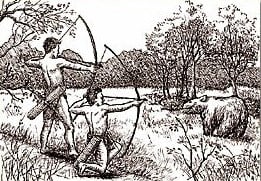

Before the coming of the Europeans, the primary big game hunting weapon was the bow and arrow, which was very accurate up to 40 yards. Some hunters could hit targets at 100 yards. The bows resembled the English longbow and were five to six feet in length. The arrows were tipped with bone points or with garfish scales. To provide greater accuracy, the arrows were fletched (feathered), often using turkey feathers. Hunters usually protected their wrists with bowguards made from leather or bark.

Another important game animal was the black bear. The bear provided both food and skins. In addition, Indians extracted an oil from the fat of the bear which was used in both cooking and curing. Bears were usually hunted in the winter while they were hibernating. The hunters would set fire to the bear’s den—usually a hollowed out tree—and then shoot it as it emerged to escape the fire.

The Seminole prized both bear meat and the oil extracted from the fat. Whenever a bear was seen, a hunting party would be organized and the animal would be tracked to its hiding place and killed.

While the bison was not as important to the Southeastern Indians as it was to the Plains Indians, it was still an important animal. Prior to the coming of the Europeans, there were moderately large bison herds in Tennessee.

The meat from deer and bison was dried over a fire. Meat dried in this fashion could be kept for several months without spoiling. Often a smoky fire, fueled by green hickory wood, was used. This gave the meat a smoked flavor.

Other important game animals included beaver, otter, raccoon, muskrat, opossum, squirrel, and rabbit. Small game and birds were often hunted with a blowgun. A hollowed piece of cane, 7 to 9 feet in length, would be used to make the blowgun. The darts were made of hardwood and would be 10 to 22 inches in length. The blowguns were accurate up to about 60 feet. No poison was used on the darts and larger animals were usually shot in the eye.

Turkeys provided an important source of both food and feathers. Both the Timucua and the Apalachee used circular fire drives in taking turkeys.

Another important and abundant bird was the passenger pigeon (now extinct) which was hunted at night during the winter. The hunters would use torches to blind the passenger pigeons which were roosting in the trees. The birds would then be knocked down with long poles.

The Indian people along the Mississippi flyway and the coastal plain also took advantage of the immense number of waterfowl. Waterfowl were usually hunted from the middle of October until the middle of April.

Along the coastal plain, the Indian people also used turtles, terrapins, alligators, crawfish, crabs, clams, mussels, and oysters for food. Among the Yamasee, turtles were considered a prize food, not only for its flesh and eggs, but also for the fact that its seasonal appearance was unfailing. Among the Timucua, alligators were hunted by thrusting a long pole (about ten feet long) down their throats. The reptile would then be flipped over on its back and arrows shot into its soft belly.

The Seminole would “fire-hunt” alligators: they would use a burning torch which would dazzle the animal. The bewildered alligator would then be speared by a hunter in a canoe. Alligator hides were placed on scaffolds to dry.

Some Florida groups, such as the Tekesta and the Seminole, also hunted manatee, a large herbivorous aquatic mammal. In the winter, the Tekesta would hunt manatee from canoes. Hunters would harpoon the manatee as they rose to the surface for air.

Among the Creek, hunting included a number of rituals which enabled the hunters to show respect for the animals. According to historian Joel Martin, in his book Sacred Revolt: The Muskogees’ Struggle for a New World:

“Native hunters did not kill game animals, consume the meat, or take the skin without carefully considering their actions.”

Prior to the hunt, the hunters would ask for the support of the spirits of the hunt and they would sing songs to draw the animals closer.

Hunters often burned the undergrowth in small patches of forest. Regularly burning the vegetation resulted in a managed environment that supported a fairly large number of deer. According to historian Daniel Usner, in his book Indians, Settlers, and Slaves in a Frontier Exchange Economy: The Lower Mississippi Valley Before 1783:

“These controlled fires both enhanced the nutritional quality of the plants that deer browsed on and eased the passage for the animals through the woods.”

This artificially stimulated the number of deer in the area.

In South Florida, historian James Covington, in his book The Seminoles of Florida, reports:

“Every spring the Seminoles set the dry grass and trees on fire so that new growth would attract the deer and turkeys.”