The Battle of Four Lakes and Spokane Plains

As a result of the 1858 defeat of forces under the command of Major Edward Steptoe by a force of 1,000 Indian warriors from several different tribes- Palouse, Coeur d’Alene, Spokan, Yakama, Pend d’Oreille, Flathead, and Columbia-600 troops under Colonel George Wright were sent out to meet the Indian forces in Eastern Washington and inflict heavy casualties upon them. Wright’s orders from the Army stated:

“You will attack all the hostile Indians you may meet, with vigor, make their punishment severe, and persevere until the submission is complete.

”

While Wright’s orders mentioned that the treaty rights of the Hudson’s Bay Company were to be observed, there was no mention of any Indian treaty rights.

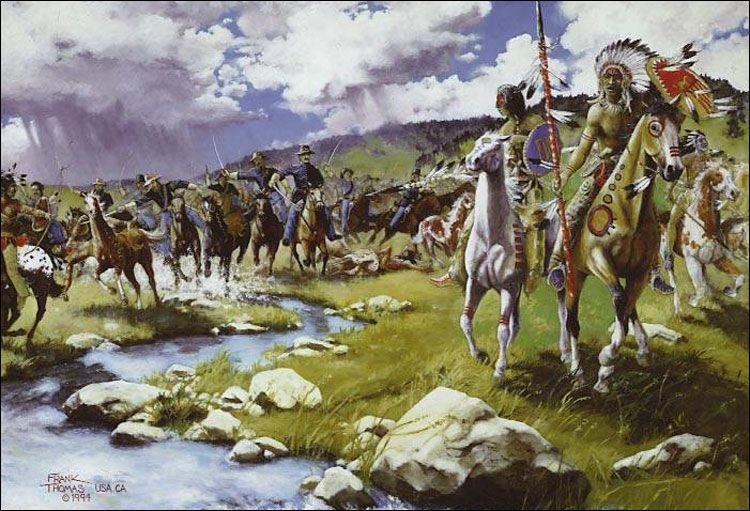

American forces swept through Eastern Washington, attacking villages, burning their provisions and supplies, shooting and hanging Indians with no concern for who they were and what they may have done. Following two major battles, one at Four Lakes and the other at Spokane Plains, the disorganized Indian forces were soundly defeated.

The Battle of Four Lakes:

At Four Lakes, about 15 miles south of Spokane Falls, Wright’s forces encountered a large force of Indian warriors. The Indians, eager for a fight, were armed with muzzle-loading muskets, lances, and bows and arrows. Writing in 1859, Lieutenant Lawrence Kip, one of the participants in the battle, reports:

“Every spot seemed alive with the wild warriors we had come so far to meet.”

According to Kip:

“Most of them were armed with Hudson Bay muskets, while others had bows and arrows and long lances.”

The army, on the other hand, was armed with new long-range rifles which proved to be deadly at 600 yards. Hudson Bay muskets, the primary Indian firearm, had a range of only 200 yards or less. The military’s new weapons and ammunition proved to be very effective.

Lieutenant Kip describes the military tactics of the Indians:

“The Indians acted as skirmishers, advancing rapidly and delivering their fire, and then retreating again with a quickness and irregularity which rendered it difficult to reach them. They were wheeling and dashing about, always on the run, apparently each fighting on his own account.”

Captain Keyes reported:

“The barbarous host was armed with Hudson Bay muskets, spears, bow and arrows, and apparently they were subject to no order or command.”

The Indians soon withdrew without inflicting any casualties on the Americans. The army estimated that 18-20 Indians were killed in the battle. The retreating Indians set fire to the prairie grasses, but the American troops pushed through the embers and smoke in pursuit.

The Battle of Spokane Plains:

At the battle of Spokane Plains, the army met and defeated an estimated 500-700 Spokan, Coeur d’Alene, Palouse, and Pend d’Oreille warriors. While no Americans were killed, two brothers of Spokan chief Spokan Garry were reported killed. A number of Nez Perce warriors aided the army as guides, spies, and pack train guards.

Lieutenant Kip described the battle:

“We had nearly reached the woods when they advanced in great force, and set fire to the dry grass of the prairie, so that the wind blowing high and against us, we were nearly enveloped by the flames. Under cover of the smoke, they formed round us in one-third of a circle, and poured in their fire upon us, apparently each one on his own account.”

Kip continues:

“Then on the hills to our right, if you could have had time to have witnessed them, were feats of horsemanship which we have never seen equaled. The Indians would dash down a hill five hundred feet high and with a slope of forty-five degrees, at the most headlong speed, apparently with all the rapidity they could have used on level ground.”

At the battle of Spokane Plains, Yakama leader Kamiakin was nearly killed when a howitzer shell hit a tree and the tree branch knocked him from his horse. Riding into battle with Kamiakin was his wife Colestah who was known as a medicine woman, psychic, and warrior. Armed with a stone war club, Colestah fought at her husband’s side. When Kamiakin was wounded, she rescued him, and then used her healing skills to cure him.

Colonel Wright reported:

“The chastisement which these Indians received has been severe but well merited, and absolutely necessary to impress them with our power. For the last eighty miles our route has been marked by slaughter and devastation; 900 horses and a large number of cattle have been killed or appropriated to our own use; many horse, with large quantities of wheat and oats, also many caches of vegetables, kamas, and dried berries have been destroyed. A blow has been struck which they will never forget.”

Most of the horses and cattle destroyed do not actually belong to “hostile” Indians, but to Indians who are not at war with the United States.

Aftermath:

The American victories at Four Lakes and Spokane Plains demoralized the Indians and the alliance among the various tribes disintegrated. Following the battles of Four Lakes and of Spokane Plains, Colonel George Wright dictated a treaty of peace with the Coeur d’Alene in Idaho. At the treaty council, Coeur d’Alene chief Vincent began by saying:

“I have committed a great crime. I am fully conscious of it, and am deeply sorry for it. I and all my people are rejoiced that you are willing to forgive us.”

In response, Colonel Wright told them:

“You must deliver to me, to take to the General, the men who struck the first blow in the affair with Colonel Steptoe. You must deliver to me to take to Walla Walla, one chief and four warriors with their families. You must deliver up to me all property taken in the affair with Colonel Steptoe.”

Wright then met with the Spokan in Washington and signed an almost identical treaty with them. When Colonel Wright met in council with the Spokan, one chief told him:

“I am sorry for what has been done, and glad of the opportunity now offered to make peace with our Great Father. We promise to obey and fulfil [sic] these terms in every point.”

In both treaty councils, he told the Indians that he had come into the Spokane country to fight and that he wasn’t interested in peace. If they were tired of war, then he would tell them the terms of peace. He stated his peace terms:

“You must come to me with your arms, with your women and children, and everything you have, and lay them at my feet; you must put your faith in me and trust to my mercy.”

Colonel Wright directed Spokan Garry to send messengers to chiefs Moses, Big Star, Skloom, and Kamiakin and inform them that they should come in for a conference. Later Colonel Wright reported:

“I warned them that if I ever had to come into this country again on a hostile expedition no man should be spared; I would annihilate the whole nation.”

When Palouse chief Polatkin and nine warriors came to talk peace with Wright, the Americans seized one of the warriors and hung him on suspicion of being involved with the murder of two miners in Colfax. There was no trial, no testimony: Wright simply sentenced him to be hung and declared:

“the fact of his guilt was established beyond doubt, and he was hung at sunset.”

The journals of other officers and civilians who witnessed the event make it clear that Wright made no effort to determine guilt or innocence. To Wright, all Indians were guilty by the very fact that they were Indian.

Reports of American brutality and their eagerness to hang Indians for imagined crimes soon spread throughout the Plateau and Plains. As a result, Indian warriors became less inclined to surrender peacefully as they knew the Americans had no interest in peace but only in the annihilation of the Indians.