Nope. Nope. Nope.

Nope. Nope. Nope.

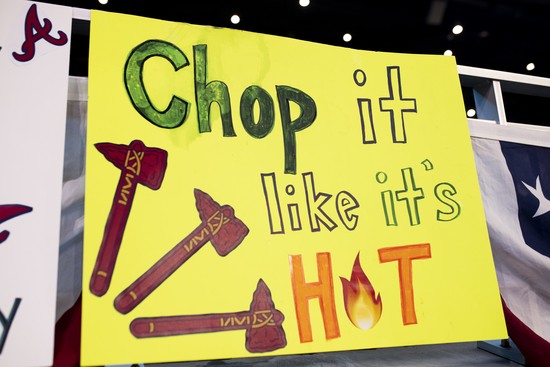

Atlanta fans didn’t find a foam tomahawk on their seats at Game 5 of the National League Division Series game against the St. Louis Cardinals, a decision the ballclub announced shortly before the game.

The change came days after comments from Cardinals pitcher Ryan Helsley, who is Cherokee. Helsley expressed his surprise and shock at Atlanta fans’ doing the racist and all-too-popular “tomahawk chop” chant, and waving the foam souvenirs as he took the mound during the eighth inning of Game 1.

“I think it’s a misrepresentation of the Cherokee people or Native Americans in general, just depicts them in this kind of caveman-type people way who aren’t intellectual,” the Cardinals rookie told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch Friday. “They are a lot more than that. It’s not me being offended by the whole mascot thing. It’s not. It’s about the misconception of us, the Native Americans, and it devalues us and how we’re perceived in that way, or used as mascots. The Redskins and stuff like that.”

Calling the continued use of Native Americans as mascots in 2019 both “disrespectful” and “disappointing,” Helsley, 25, said that he researched the tomahawk chop after the game, as well as the decades of efforts to get rid of it. “It’s interesting that people have suggested that they should change it, and it’s still the same thing,” he said.

Helsley’s “interesting” research likely revealed that the Atlanta team isn’t exactly named for Native Americans; as the Post-Dispatch and many a sports history archive report, the “Braves” name, chosen while the team was still in Boston in the early 20th century, was inspired by imagery from Tammany Hall. Tammany Hall, of course, was a society founded for “pure Americans” that snatched its name from the Lenape tribe and leaned heavily on Native American imagery, even calling its headquarters “the WigWam.”

As USA Today noted in 2016, the Boston Braves, named in 1912, and the Cleveland Indians, named in 1915, offer a particularly painful snapshot of the cruelty of that time period.

Scores of high schools and colleges across the country assumed these and other Indian team names in the 1920s and 1930s, even as so-called civilization regulations forbade Native Americans to speak their languages, practice their religions or leave their reservations.

This meant real American Indians could not openly perform ceremonial dance at a time when painted-up pretend ones could prance on sidelines, mocking the religious rituals of what a dominant white culture viewed as a vanishing red one.

Perhaps Halsey’s googling led him to this 1991 article, written almost three years before the Oklahoma native was even born. It offers a glimpse into the long battle Native Americans have been fighting against the mascot-ization of their people, while normalizing that very act.

Jane Fonda and Ted Turner did the “tomahawk chop” together. Even Jimmy Carter joined in the Atlanta Braves mania by using the swinging elbow-to-hand motion to root, root, root for the home team.

But the nationally televised sight of these celebrities appropriating Indian symbols along with thousands of other Braves baseball fans who sang an Indian-like chant while waving toy tomahawks has outraged some American Indians.

The Braves were on the verge of making the World Series at the time, which would have taken them to Minneapolis for Game 1—a city that, at the time, was home to about 23,000 Indigenous people, making it “one of the largest urban concentrations” of Native Americans in the country. Leaders were planning to protest if the Braves and their tomahawk chop descended on their city.

Phil St. John, a member of the Dakota Sioux tribe, was, in 1991, the head of Concerned American Indian Parents, and had already fought to end the mascot-ization of Native Americans in Minneapolis. He made it clear how the entire Atlanta brand and the actions of the fans came across. “People in Atlanta don’t realize they’re talking about an entire race of people, and it hurts to see these white boys in the bleachers singing and chanting like that.”

It also wasn’t just Minnesota Native Americans, either. Atlanta resident Aaron Two Elk, then-regional director of the American Indian Movement, told the Associated Press that the tomahawk chop was “dehumanizing, derogatory and very unethical,” noting that this particular form of fan fervor “extends a portrayal of Native American people as being warlike, aggressive, having a savage approach.”

The Atlanta team leadership and fans, of course, were having none of it. The team’s general manager at the time, John Schuerholz, simply dismissed Native Americans’ view of the tomahawk chop entirely, and replaced it with an opinion he liked better, insisting that “we view (the Chop) as very positive and certainly doing nothing to discriminate or in any way negatively impact.”

Perhaps Helsley came across this article, which notes that Native Americans have been pushing back against the mascot-ization of their humanity since 1968. (Note: Click through for a fascinating look at the unique relationship the Seminole Tribe of Florida has with Florida State University, home of the “Seminoles” and the fan base that originated the tomahawk chop.)

Or maybe Helsley’s research led him to learn that Dartmouth and Stanford managed to discard their racist mascots in the 1970s, just a few years after Native Americans voiced criticism, and the world didn’t end. Did he learn that the state of Maine banned Native American mascots just a few months ago? Mayhaps the pitcher’s googling took him to this discussion of the danger of the Kansas City football team’s branding, where a clinical psychologist noted that “American Indians are the only group of people in this country, or anywhere else for that matter, who are forced to tolerate racist team names and logos in such a widespread way.”

🤮😡🤮😡🤮

🤮😡🤮😡🤮

Of course, this wasn’t the first battle to eliminate Native American mascots. But so many of them end in the same way: People who aren’t Native American declare that they don’t see anything wrong with the Washington NFL team name, or the Cleveland baseball mascot, or the Kansas City NFL team, or, or, or … and the media, the general public, and the teams themselves then elevate that public opinion as the one that matters most. Tradition! That’s what Washington owner Dan Snyder invokes when he stands firm that he will “NEVER— you can use caps” change the team name, a name that many media outlets no longer use in their sports coverage. A team name that literally disqualified both Washington and Kansas City for philanthropic award consideration.

This fan of the Kansas City football team, which also uses the tomahawk chop, offered some strong words to Deadspin in August.

The tomahawk chop is so fucking racist and they just built a new section in the stands specifically for the drum so we can be more fancily racist.

Cleveland owner Larry Dolan took this know-it-all stance in 2001: “I firmly reject that Wahoo is racist. I think I understand racism when I see it.”

Indians’ Chief Wahoo target of Opening Day protests again & it’s time to finally take notice http://t.co/60LFbR7Zmi pic.twitter.com/lj5v1oKWVG

— Indigenous (@AmericanIndian8) April 4, 2015

In addition to actual Native American people, multiple studies and mental health professionals have acknowledged the harm that the mascot-ization of Native Americans has caused and can cause. Here’s a statement from the American Sociological Association:

WHEREAS the continued use of Native American nicknames, logos and mascots in sport has been condemned by numerous reputable academic, educational and civil rights organizations, and the vast majority of Native American advocacy organizations, including but not limited to: American Anthropological Association, American Psychological Association, North American Society for the Sociology of Sport, Modern Language Association, United States Commission on Civil Rights, National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, Association of American Indian Affairs, National Congress of American Indians, and National Indian Education Association;

NOW, THEREFORE, BE IT RESOLVED, THAT THE AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION calls for discontinuing the use of Native American nicknames, logos and mascots in sport.

That resolution is 12 years old, by the way. This one, from the American Psychological Association, is even older:

The APA is calling upon all psychologists to speak out against racism, and take proactive steps to prevent the occurrence of intolerant or racist acts and recommends the immediate retirement of American Indian mascots, symbols, images and personalities by schools, colleges, universities, athletic teams and organizations.

This document is based on the APA American Indian Mascot Resolution adopted by the APA’s Council of Representatives in September 2005.

Which brings us back to Atlanta, and the team’s abrupt turnaround on the tomahawk chop after Ryan Helsley spoke out. While the team did not distribute foam tomahawks on Wednesday night, that didn’t have much of an effect on the pervasive culture of chop that both the team and fans alike have created. People who heard about the change in time just brought their own tomahawks, and those who didn’t just used their arms.

It’s not like Atlanta made major changes yet. The team’s official hashtag remains “#ChopOn,” and the team’s signature tomahawk was still on uniforms, fan gear, the stadium walls, and the field. “It’s everywhere,” Helsley asserted.

The average fan likely didn’t even realize why they didn’t get a cheap souvenir to wave about, much less that a Cherokee pitcher named Ryan Helsley was the overdue impetus. Instead Atlanta fans saw their team get crushed on their way to elimination from the postseason, with the Cardinals scoring 10 unanswered runs in just the first inning—which was also when the less-foamy tomahawk chop made its first appearance.

“(It)hurts to see these white boys in the bleachers singing and chanting like that.” Phil St. John, Dakota Sioux, 1991

“(It)hurts to see these white boys in the bleachers singing and chanting like that.” Phil St. John, Dakota Sioux, 1991

There were also plenty of complaints, including from elected Republicans, about the lack of free foam. Apparently frustrated after being deprived of appropriating one culture, Georgia state Rep. Trey Kelley called the Atlanta loss “karma.” He was far from alone in his dismay.

Debbie Dooley, a Georgia tea party organizer, said the Braves “jinxed itself by catering to a politically correct snowflake” and suggested the team change its name to “Atlanta Snowflakes.”

Call them the Snowflakes or whatever you wish: Atlanta is done for 2019. Meanwhile, reliever Helsley kept his arm warm and didn’t throw a pitch on Wednesday.

Leave a Reply