Under the Constitution, Indian tribes are considered to be nations and thus all dealings with the tribes were to be conducted by the federal government, not the states. Administratively, the relationships between the United States and the various Indian nations should have been a foreign policy matter. However, from the very beginning Indian affairs were under the authority of the Secretary of War rather than the Secretary of State. Part of this was due to the personalities of George Washington’s administration: Washington was closer to Henry Knox, the Secretary of War, and Washington wanted to have more control over Indian affairs. Thus, under the Washington administration, Indian affairs was a part of the War Department and under the direction of the Secretary of War. In 1818, the Secretary of War, John Calhoun, was in charge of Indian affairs in the United States.

Secretary of War John Calhoun reported to the House of Representatives that the Indians west of the Mississippi River had become less warlike since their contact with Europeans. He proposed three basic changes to the aimless Indian policy of the past: (1) stop considering Indian tribes as nations, (2) seek to save Indians from extinction, and (3) inculcate among the tribes the concept of ownership of land. He stated:

“By a proper combination of force and persuasion, of punishment and rewards, they ought to be brought within the pales of law and civilization.”

He also said:

“The time seems to have arrived when our policy toward them should undergo an important change…Our views of their interest, and not their own, ought to govern them.”

Nearly two centuries later, Duane Champagne, in an essay in This Week From Indian Country Today, would write:

“Throughout much of American history, those parties that have been primarily responsible for making Indian policy have tended to emphasize the needs and interests of American society rather than those of tribal nations.”

Clifford Trafzer and Richard Scheuerman, in their book Renegade Tribe: The Palouse Indians and the Invasion of the Inland Pacific Northwest, put it this way:

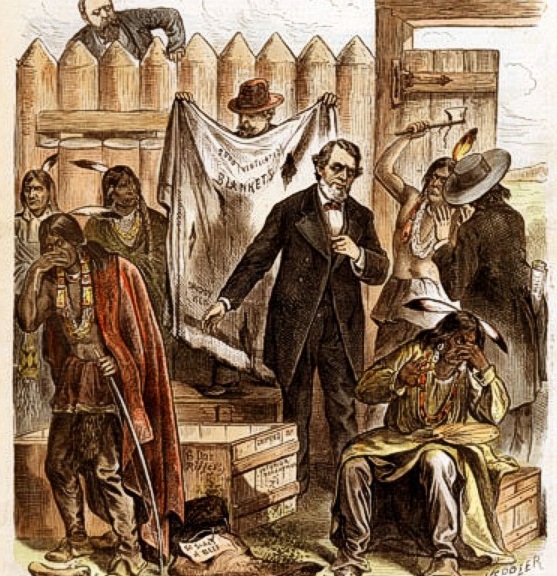

“American Indian policy was designed for the benefit of whites, not Indians, and was carried out by determined agents far more concerned with their professional duty and the destiny of their nation than they were with Indians.”

With regard to the “civilized” tribes in the Southeast, Secretary Calhoun recommended reducing their settlements to a reasonable size and moving them west of the Mississippi. American negotiators put pressure on tribes such as the Chickasaw and Cherokee to give up their traditional tribal homelands and move west. Here they would be free from further demands on their lands by the various states.

Concerning education, Secretary Calhoun proposed compulsory attendance at schools for all Indian children. He recommended that the government should provide the tribes with an annuity to fund the schools. He suggested that in the beginning these schools focus on vocational education until such time as Indians showed an aptitude for the liberal arts. The first schools should concentrate on teaching agricultural techniques, homemaking, Christianity, and citizenship. Government policy at this time held that Indians had to be converted to Christianity.

Secretary Calhoun’s recommendations were ignored by Congress, but continued to guide the War Department in its dealings with Indians.

International Boundary

The United States and England agreed to the 49th parallel of latitude as the international boundary between the United States and Canada. No Indian leaders were consulted in making this agreement even though this boundary impacted many American Indian nations. Many Indian nations were divided by this arbitrary line. For example, many Ojibwa living in the Red River area found themselves now living in the United States rather than Canada.

Leave a Reply