By 1869, the Indian policies of the United States government were largely focused on reservations. It was generally felt that by confining Indians to small reservations out of the way of non-Indian settlement, Indians could be made into English-speaking, Christian farmers. Or they could become extinct.

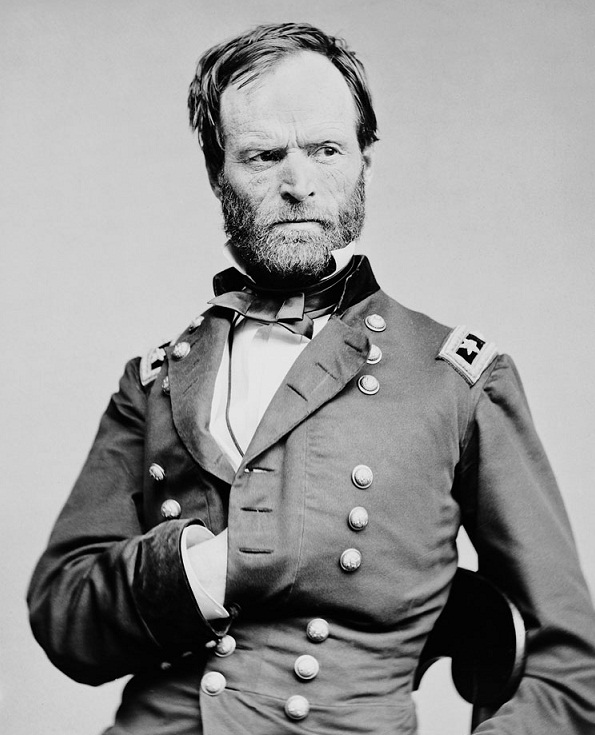

The well-known Indian-fighter General William T. Sherman once defined a reservation as “a tract of land entirely occupied by Indians and entirely surrounded by white thieves.” Anthropologist Anthony Wallace, in his book The Death and Rebirth of the Seneca, writes:

“The reservation system theoretically established small asylums where Indians who had lost their hunting grounds could remain peacefully apart from the surrounding white communities until they became civilized. It actually resulted, however, in the creation of slums in the wilderness, where no traditional Indian culture could long survive and where only the least useful aspects of white culture could easily penetrate.”

In an article in American Indian Quarterly, Tracy Leavelle writes:

“Reservations have often been perceived as places of decline and dependence, as sites where Indian peoples confronted an incomplete assimilation within a larger society that abused or ignored them.”

Some reservations were run like concentration camps where the Indian inmates were seen as prisoners.

Corruption in the administration of Indian reservations was wide-spread. Indian reservations provided ample opportunity for fraud. First, there were the Indian agents on the reservation. Poorly paid, untrained for the job, many Indian agents saw this as an opportunity to get rich. It was not uncommon for the Indian agent to have a store in an off-reservation town which sold the goods which had been intended as annuities for the reservation.

Briefly described below are some of the reservation events of 150 years ago, in 1869.

Fort Hall Reservation

In Idaho, the Fort Hall Reservation was opened for the Shoshone and Bannock. In their book An Introduction to the Shoshoni Language: Dammen Daigwape, Drusilla Gould and Christopher Loether report:

“The opening of the reservation began a period of ethnic cleansing and hardship for the Shoshone-Bannock unlike anything they had ever experienced before. They were forcibly removed from their homes and sent to the reservation. On the reservation they found little food, no opportunities, and very little hope for the future.”

In Idaho, the Bannock under the leadership of Tahgee were assigned to the Fort Hall Reservation by Presidential executive order. In his book Chief Pocatello, Brigham Madsen reports:

“Chief Tahgee was an impressive and strong Indian leader who commanded the respect of his followers as well as every white official who met him.”

In moving to Fort Hall, the Bannock were to give up all rights to areas outside of the reservation, including Camas Prairie.

In Idaho, 1,150 Boise and Bruneau Shoshone, along with 150 Bannock were moved to the Fort Hall Reservation under military escort. The Indians had been living in a refugee camp near Boise. Historian John Heaton, in his book The Shoshone-Bannocks: Culture and Commerce at Fort Hall, 1870-1940, reports:

“Hunger, exposure, and a measles epidemic had ravaged the refugees over the winter and left them in a weakened condition to confront the severe weather they experienced on the journey.”

The soldiers expressed little sympathy or concern for the Indians they were herding, and some Indians were killed for slowing the procession down.

Navajo Reservation

In Arizona, the Indian Office purchased 35,000 sheep and goats to issue to the Navajo as rations but only 14,000 arrive. Historian Kathleen Chamberlain, in her book Under Sacred Ground: A History of Navajo Oil 1922-1982, reports:

“Families took their stock ration and disappeared into the interior of Dinétah to live quietly isolated lives. Undoubtedly half of the stock was by necessity slaughtered that first winter, but with Navajo thrift and care herds multiplied, thereby freeing many from having to rely on government handouts.”

In their book A History of the Navajos: The Reservation Years, Garrick Bailey and Roberta Glenn Bailey report:

“Although they were impoverished and often hungry, most people refrained from butchering the few animals they owned, and relied on hunting and gathering of wild plants.”

Hopi Reservation

The United States officially established an Indian Agency for the Hopi. However, the agency was located in Fort Wingate rather than near the Hopi pueblos in Arizona. In addition, the agency was officially named the “Moqui Pueblo Agency,” a name which the Hopi feel is insulting. In his book Pages from Hopi History, Harry James writes:

“It was not an auspicious beginning of official relations between the government of the United States of America and the independent villages of the three Hopi mesas.”

Omaha Reservation Allotment

American Indians had been farmers for thousands of years prior to the formation of the United States, but Indian farming was generally done on communal lands, a practice which was offensive to the American government. The government policy-makers, felt that Indians should learn about private property and greed by farming their own privatized parcel of land. Thus, the government sought to give each Indian family an allotment, an individual parcel of land. In Nebraska, the process of allotting Omaha lands began. The Indian agent assigned 160-acre parcels to 130 of the 278 family heads.

Blackfoot

In Montana, the Blackfoot Indian Agency was moved from Fort Benton to a site on the Teton River about 75 miles northwest of Fort Benton. Fort Benton had not been friendly toward Indians. In his book Blackfoot Fur Trade on the Upper Missouri, John Lepley reports:

“All the townspeople wanted were the Indian lands, the huge profits from the annuities, the opportunity to trade whiskey for robes and the right to shoot and ask questions later.”

In moving the agency, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs felt that this would reduce the number of Indians on the streets of Fort Benton and reduce the chances of their being shot and having their bodies pitched into the river or stuffed down a well.

Assiniboine and Gros Ventre

In Montana, the Assiniboine were assigned to the Milk River Agency. At this time there were two divisions of Assiniboine in Montana: (1) the Upper Assiniboine bands, led by Long Hair and Whirlwind and intermarried with the Gros Ventre, and (2) the Canoe Paddler Band led by Red Stone. The Canoe Paddler Band was associated with the Yankton, Yanktonai, and Santee Sioux.

Yanktonai Sioux

In Montana, about 1,000 Upper Yanktonai arrived at Fort Buford and demanded a reservation. Leaders included: Medicine Bear, Thunder Bull, His Road to Travel, Shoots the Tiger, Afraid of Bear, Catches the Enemy, and Heart. In addition, one band of Sisseton Sioux under Brave Bear and Your Relation on the Earth were with the Yanktonai.

One week later the Takini band of Upper Yanktonai under the leadership of Calumet Man, Afraid of Bull, Long Fox, Eagle Dog, and Standing Bellow arrived at the fort and asked for a reservation.

Pueblos

Congress passed legislation which formally recognized the Santa Ana Pueblo land grant in New Mexico.

In New Mexico, a special inspector for the Indian Office recommended that the Pueblos be declared citizens and required to pay taxes on their crops, herds, and orchards.

Klamath Reservation

In Oregon, Modoc leader Captain Jack moved back to the Klamath Reservation. He brought with him 43 men, women, and children.

Eastern Cherokee

In North Carolina, the Cherokee adopted a new constitution and tribal roll.

Wind River Reservation

In Wyoming, Arapaho leaders Medicine Man and Black Bear visited the commanding officer at Fort Fetterman and ask to settle on land which had been set aside for the Shoshone. The Arapaho and Shoshone had been traditional enemies.

California

In California, the Mechoopda village on the Rancho del Arroyo Chico was relocated. The traditional domed earthen homes were replaced by wood houses.

In California, the Smith River Indian Farm was abandoned because of non-Indian pressures.

Ottawa and Chippewa

In Kansas, the Ottawa and a Chippewa band were removed to Indian Territory.

Sac and Fox

In Oklahoma, the Sac and Fox arrived at their new reservation. For many, this was their fourth removal in two generations. Their removal from Kansas took only 19 days and the mild winter weather created few difficulties. Once in Oklahoma, they had to live in tents until they could construct new homes.

Southern Cheyenne and Arapaho

In Oklahoma, a reservation on the Canadian River was established for the Southern Cheyenne and Arapaho by executive order of President Ulysses S. Grant. The new reservation was assigned to the Orthodox Friends (Quakers). The new Indian agent was Brinton Darlington. In an article in the Chronicles of Oklahoma, Sandra LeVan reports:

“Agent Darlington soon won the respect and confidence of the Indians under his care.”

Loyal Shawnee

A large Shawnee group, known as the Loyal Shawnee, relocated to Oklahoma from Kansas. They purchased land from the Cherokee and were incorporated into the Cherokee nation.

Potawatomi

In Oklahoma, a delegation of Citizen Potawatomi looked for land for their new reservation. Instead of selecting land from the Cherokee Reservation, as directed in their treaty, they chose land that had previously belonged to the Creek and Seminole.

Ute

In Utah, the San Pitch Ute, once led by Autenquer (Black Hawk), followed the civil leader Tabby-to-kwana to the Uintah Valley Reservation. The Ute had been assured that they would be able to continue to hunt and gather on all public lands.

Gosiute

In Utah, the Indian agent for the Gosiute, noting that they had undertaken farming, suggested that a separate reservation be established for them.

Crow

In Montana, the first Indian agency for the Crow was established on the south bank of the Yellowstone River near its confluence with Mission Creek.

In Montana, the River Crow were officially assigned to the Mountain Crow Agency. The River Crow had been living in the Milk River area with the Gros Ventre and Assiniboine.

Leave a Reply