The Modoc homeland is the Tule Lake area on the border between California and Oregon. In 1872-1873, the U.S. Army engaged a small band of Modoc under the leadership of Captain Jack (Kintpuach) in what has been called the Modoc War.

The United States government, in its infinite ignorance of American Indian cultures, had assigned the Modoc to the Klamath Indian Reservation in Oregon. While the reservation included some of the traditional homelands of the Klamath, it did not include any of the traditional Modoc homelands. Food shortages, conflicts with the Klamath, and the government’s suppression of traditional religious practices resulted in a number of Modocs leaving the reservation, an action which was illegal under Oregon law and which some officials felt was illegal under federal law.

Those who left the reservation were considered “hostiles” by the government. The Modoc leadership included: Kintpuash (called Captain Jack by the Americans); Chichikam Lupalkuelatko (called Scarfaced Charley by the Americans, he was generally considered to be the principal military strategist); Hooker Jim; Curley Headed Doctor; Schonchin John; and Boston Charley.

The 1st Cavalry, stationed at Fort Klamath, was ordered to compel the Modoc, by force if necessary, to return to the Klamath Reservation. At daybreak, the troops arrived at Captain Jack’s Modoc camp. There are conflicting stories about what actually happened next, but what is clear is that gunfire was exchanged. Military historian Peter Cozzens, in an article in MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History, describes the battle this way:

“The fighting was over in five minutes. Eight soldiers and one Modoc were killed. When the smoke from the gunfire lifted, the Indians were gone, paddling their canoes hard across Tule Lake.”

Some reports indicate that only one soldier was killed and seven were wounded. Regardless of the casualty count, Captain Jack’s band took refuge in lava beds.

While the soldiers were engaged in fighting Captain Jack’s band, a group of about a dozen American settlers decided to attack Hooker Jim’s Modoc camp, According to military historian Peter Cozzens:

“The warriors drove off the Oregonians with a single volley, but not before a soldier’s load of buckshot killed a Modoc baby.”

The Modocs, enraged by the attack, rode hard to join Captain Jack in the lava beds. The Indians killed 12 settlers (some reports indicate 14) on their flight south.

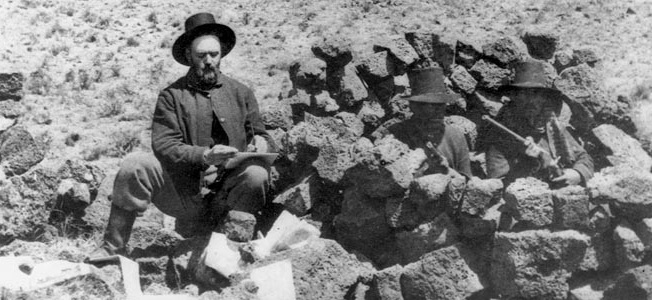

The lava beds near Tule Lake, California are a maze of twisted stone, hidden caves, lava flows, and natural trenches. This was within traditional Modoc territory and was an area well-known to them. The Modoc called the area “land of burned-out fires.” In an article in Archaeology, Julian Smith writes:

“Eruptions as recent as 800 years ago have left raw expanses of lava, tuff, and obsidian pocked by caves and laced with the largest known concentration of lava tubes in North America. Here, amid a maze of volcanic walls, boulders, fissures, and holes, 50 to 60 Modoc warriors held off a much larger force of U.S. Army soldiers for half a year.”

The spiritual leader of the group was Curley Headed Doctor. In the lava beds, he had a rope of tule reeds woven, dyed red, and stretched around the campsite. He claimed that no American soldier could cross this rope. Since no soldiers crossed this rope during the conflict, the Modoc assumed that it worked.

In early 1873, a force of about 300 soldiers and volunteers from Oregon and California attacked the Modocs in their lava beds stronghold. Julian Smith reports:

“Concealed Modoc snipers picked off Army soldiers as they crossed open fields of sagebrush, and dense fog made it impossible for the soldiers to use their mountain howitzers with any accuracy.”

The battle was a disaster for the Army: 12 killed and 25 wounded. The Modocs acquired Army rifles and ammunition left behind during the retreat. In his book The Great Circle: A History of the First Nations, Neil Philip reports:

“Curley Headed Doctor’s medicine had worked: first he brought a fog to confuse the enemy, and then he turned the white men’s bullets so that no Modoc was hurt.”

Both sides dug in for what would become a six-month siege. Julian Smith reports:

“The Modoc also built corrals for 100 or so wild cattle that had roamed the lava beds and constructed camps consisting of small lodges out of willows and mats woven from tule reeds.”

The Americans set up a peace commission to meet with Captain Jack and others at the Lava Beds. In an article in the Oregon Historical Quarterly, Doug Foster reports:

“The army wanted Captain Jack’s band removed to the Klamath reservation, while Captain Jack wanted a reservation set aside for his band on their ancestral lands.”

The Americans also asked for the Modocs to turn over Hooker Jim to be hung for killing American settlers.

While the truce between the army and the Modoc called for no hostile movements during the peace negotiations, the army moved its soldiers and canons forward in violation of the truce. In desperation, the Modocs made plans to kill General E.R.S. Canby, the army field commander. Julian Smith reports:

“In the stronghold, Jack argued for reaching a peaceful settlement. Other Modoc chiefs wanted to keep fighting. They pointed out how the white had killed Modoc people, including some of their own family members, under flags of truce more than once. They may also have thought if they could kill the Army leaders, the troops would be demoralized and end the siege. Jack was mocked and overruled.”

While Canby was warned of the plans by an interpreter (Winema, a bilingual woman who was Jack’s cousin), he insisted that the Modocs would not dare to carry it out with so many soldiers around. However, the Modoc carried out their plans and General E.R.S. Canby and the Reverend Eleazer Thomas were killed. The Indian agent, Alfred B. Meacham, was wounded and Winema dragged him to safety. In his book Who Was Who in Native American History: Indians and Non-Indians From Early Contacts Through 1900, Carl Waldman reports:

“As Schonchin John began to scalp him, Winema called out that soldiers were coming. After the Modocs had fled, she wrapped Meacham in her saddle blanket and set out for help.”

The Modoc attack on the peace commission intensified the Modoc War. Julian Smith reports:

“Canby was the only full general killed during the Indian wars and the ambush made international news. It also turned public opinion against the tribe. The Army brought in hundreds more soldiers to remove the Modoc once and for all.”

From an Army perspective, Edward Hathaway, in his book The War Nobody Won: The Modoc War from the Army’s Viewpoint, points out:

“The Modoc War was fought by an inexperienced army of poorly trained and poorly supported soldiers led by incompetent officers.”

His observations about Captain Jack:

“Captain Jack proved to be a fine natural strategist and tactician. His handling of the defenses against the attacks on the stronghold was brilliant.”

In one incident, the army soldiers found an old woman—described as being 80 or 90 years old—in the rocks near the stronghold. The lieutenant asked:

“Is there anyone here who will put that old hag out of the way?”

A soldier then placed his carbine to her head and shot her. One of the witnesses to the event, Maurice Fitzgerald, would later write:

“This incident goes to show that humanity is about the same the world over and not to any great extent affected by religion, language, or national boundaries.”

On April 17, 1873, 700 professional soldiers—not the poorly trained volunteers previously used—attacked the Modocs. They were accompanied by scouts from the Warm Springs Reservation in Oregon. Julian Smith reports:

“After fighting their way into the stronghold, the soldiers found it deserted except for a few Modoc who were too sick or injured to travel. The defenders had slipped out under cover of darkness and headed south.”

During the battle, six soldiers were killed and 17 wounded. Among the Modoc there were only two or perhaps four casualties

Two weeks after the battle, a large patrol (60 soldiers) blundered into a carefully planned ambush at Hardin Butte, four miles south of the Modoc stronghold. The army and the press labeled this a massacre: 22 soldiers and all five officers were killed. According to Edward Hathaway it was not a massacre:

“It was a poorly planned, poorly executed move that was carried out in a rather lackadaisical manner. It appeared to be more of a stroll off to a picnic than a military operation.”

One of the Modoc leaders, Scarface Charley, called down to some of the survivors:

“We don’t want to kill you all in one day”

Through this generosity several soldiers escaped.

Shortly after this battle, the Hot Creek band, famished and weary, surrendered. A short time later Captain Jack’s band also surrendered. In the peace negotiations, Captain Jack told the Americans:

“This is my home; I was born here, always lived here, and I don’t want to leave here.”

Schonchin John told them:

“I would like to live in my own country.”

Julian Smith writes:

“To defeat some 60 native warriors, the government spent an estimated $400,000-$500,000, the equivalent of $8.4 million-$10.5 million today, and counted more than 100 casualties. In comparison, the six square miles the Modoc had requested to settle on would have cost $20,000.”

The captured Modoc were marched under heavy guard to Fort Klamath, a military post near the Klamath Reservation. Thirteen of the warriors were locked in cells in the guardhouse. The other 140 men, women, and children were confined to a stockade that measured 150 feet by 50 feet.

Aftermath

Following the Modoc War, 153 Modoc were shipped from the Klamath Reservation in Oregon to the Quapaw Agency in Oklahoma. The Modoc were sent to Oklahoma as prisoners of war.

The commission investigating the Modoc War reported:

“The causes leading to war were the dissatisfaction of Captain Jack’s band of Modocs with the provisions and execution of the treaty of October 1864 and refusal to abide thereby” and “The immediate cause of hostilities was resistance by the Indians to military coercion.”

Maurice Fitzgerald, one of the army privates in the Modoc war, would later write:

“Taking everything into consideration, its must be admitted that the government dealt harshly with this little band of brave, if treacherous, savages. They were fighting for what they deemed an inalienable right to retain possession of a locality that had belonged to them and their ancestors from time immemorial, and from which it was sought to forcibly eject they for no good cause, as they could see it.”

Edward Fox, writing in the New York Herald in 1873, reports:

“There is, however, little doubt that the Indians have been badly treated, and if the whites had kept faith with them, there would have been no disturbance at all.”

Local newspapers, however, condemned the Modocs, painting them as “fiends” and “barbarians” while praising the Americans who killed them as defenders of their farms and ranches.

Indians 101/201

Indians 101/201 is a series exploring American Indian histories, cultures, and current concerns. lndians 201 is an expansion of an earlier essay.

Leave a Reply