Sealth was born about 1786. His father, Schweabe, was Suquamish and his mother, Scholitza, was Duwamish. As a young boy in 1792, he witnessed the arrival of the first Europeans: British Captain George Vancouver entered Puget Sound and traded with the Suquamish.

Among the Salish-speaking tribes of the Northwest Coast, children often seek spiritual helpers through a vision quest. In his biography of Seattle in the Encyclopedia of North American Indians, Jay Miller reports:

“As a child Seattle was sent out to quest for spirit power, and he was successful at least once: Thunder, a powerful being, gave him abilities as a warrior and orator.”

As a young adult, Sealth successfully stopped an attack against the Suquamish by the Cascade tribes. About 1825, he set up a successful ambush on a river bend near present-day Auburn. As a result of this military success, he was designated as a tribal chief. From 1820 to 1850 he was a spokesman and diplomat for the Suquamish and other Puget Sound tribes in their dealings with fur traders and missionaries.

In 1833, the Hudson’s Bay Company established Fort Nisqually to trade with the Southern Coast Salish. Sealth was a frequent visitor at the fort and was known to the traders as Le Gros or See Yat. Jay Miller writes:

“By this time, Seattle had led many successful raids and gained prestige throughout southern Puget Sound. At the fort, he familiarized himself with European ways while insisting on his prerogatives as the leader of a loose Lushootseed confederacy.”

In 1838, Sealth converted Catholicism and was baptized as “Noah.” In his his biography of Seattle in Notable Native Americans, Tom Kunesh writes:

“With his new-found faith, he instituted morning and evening church services among Native Americans that were continued even after his death.”

About 1847, Sealth led a raid against the Chemakum (non-Salish) village of Hadlock. One of his sons had killed another Suquamish and Sealth led the raid to regain his standing among the Suquamish. During the raid, his son was killed. This was Sealth’s last raid: he stopped being a warrior and focused on being a diplomat.

In 1852, he formed a partnership with David “Doc” Maynard from Olympia to set up a fishery on Elliot Bay. He hired the Duwamish to help him build a new store and named it the “Seattle Exchange” after Chief Sealth. He filed a city plat with Seattle as the new settlement’s name. Maynard obtained Sealth’s permission in exchange for an annual payment during his lifetime. Among the traditional Suquamish, the names of the dead are not mentioned for at least five years and the names of dead chiefs are not to be uttered for ten. The payment, a kind of royalty, was an acknowledgment of the pain which would be inflicted on Sealth after his death because a variation of his name—Seattle—would continue to be spoken.

Seattle became an important economic outlet for the Suquamish and Duwamish people and allowed them easier access to American goods.

In 1854, Sealth gave what has been described as a “moving” speech to the Washington territorial governor on the status of the Suquamish and Duwamish people. It is not clear whether Sealth gave his speech in Suquamish or Dumanish, neither of which was spoken by the governor. His words were then translated into Chinook Wawa, a trade language with a limited vocabulary and grammar, and then into English for the representatives of the American government. Today, there are at least four versions of his purported speech, all of which tend to be rather eloquent and don’t seem to reflect the limitations of having been translated through a trade language.

In 1855, Washington Territorial Governor Isaac Stevens held a treaty council with 82 chiefs at Point Elliot near present-day Everett. As a result of the resulting Treaty of Point Elliot, fifteen tribes signed over to the United States 10,000 square miles of their ancestral lands. Each of the tribes was to receive $150,000 in annuities to be delivered over a twenty-year period. In this treaty, the Suquamish gave up most of their land in exchange for a small reservation, health care, education, and acknowledgment and protection of their rights to continue to fish and hunt.

Stevens had Chief Sealth sign the treaty as chief of the Duwamish, Suquamish, and allied tribes. In an article in the Western Historical Quarterly, Alexandra Harmon reports:

“An advisor had told Stevens that Seattle belonged to the Suquamish but lived with and commanded the allegiance of the Duwamish. Many other sources, including people purporting to speak for the Duwamish tribe, have since identified him as affiliated with the Duwamish.”

The treaty negotiations were conducted in Chinook Wawa, a trade jargon. Sealth, however, claimed that he did not speak this language. Jay Miller reports:

“Denying knowledge of this jargon was a curious step for an intertribal figure to take, though in doing so Seattle called attention to his stature since he then required, and was provided with, a special interpreter to translate from jargon into Lushootseed for him.”

The 1855 treaties imposed on the Indian nations of Washington by Governor Isaac Stevens led to a war east of the Cascade Mountains led by Kamiakin, and the Puget Sound War led by Leschi. Despite these wars and the many grievances of the Indian people against the American invaders, Sealth kept his people at peace. Tom Kunesh writes:

“In accordance with the treaty stipulations, Seattle and his people moved to the Port Madison reservation, located west-northwest across the Puget Sound from the current city of Seattle, on the east shore of Bainbridge Island.”

At the new village, Sealth lived in the Old Man House, the largest winter house in the Puget Sound area. Archaeologists estimate that it was 500 feet long and 40-60 feet wide, but some reports indicate that during Sealth’s time, the house was actually 1,000 feet long. The house had been originally constructed about 1800 and was expanded over the years.

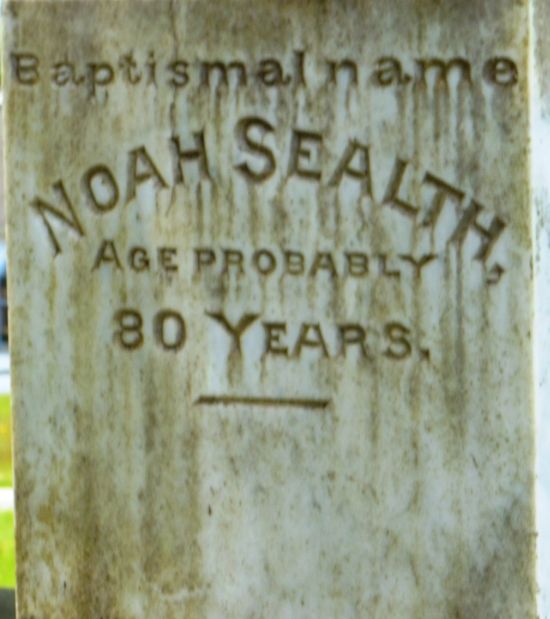

He died in 1866 at the Old Man House winter village and is buried in the Suquamish cemetery. Sealth was 78 when he died.

Sealth had at least two wives: Ladaila (Duwamish) who was the mother of Angeline, and Owiyal, who was the mother of George, Jim, and at least three girls.

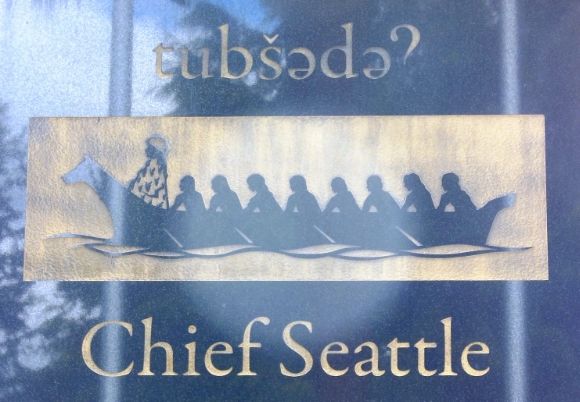

Chief Seattle’s (Sealth’s) Grave:

Shown below are some photographs of Chief Sealth’s grave.

Indians 101/201

Indians 101/201 is a series exploring American Indian histories, biographies, arts, cultures, and current concerns. The 201 designation means that the essay has been revised and expanded since it was first posted. More biographies from this series:

Indians 201: James Welch, Novelist

Indians 101: Ilchee, a Powerful Chinook Woman

Indians 201: Frank White, Pawnee Prophet

Indians 101: Joseph LaFlesche, Omaha Chief

Indians 201: Dr. Susan LaFlesche, Omaha Physician

Indians 101: Susette La Flesche, Indian Activist

Indians 101: Nakaidoklini, Apache Spiritual Leader

Leave a Reply