There are more than 6,000 languages in the world and only about 100 of these developed their own writing system. For most of these writing systems, we know relatively little about the individuals who actually created the writing system. The exception to this is the development of the Cherokee writing system in the nineteenth century by Sequoia ((also spelled Sequoyah), a monolingual Cherokee.

In his entry on the Cherokee language in the Encyclopedia of North American Indians, Duane King reports:

“The Cherokee writing system was devised by Sequoyah, the only person in recorded history to accomplish such a feat without first being literate in at least one language.”

Cherokee

As the European invasion of North America began, the Cherokees had been a farming people for many centuries and the Cherokee nation was composed of many politically autonomous villages. At the time of European contact, the Cherokee were divided into three broad groups: (1) the Lower Towns along the rivers in South Carolina, (2) the Upper or Overhill Towns in eastern Tennessee and northwestern North Carolina, (3) the Middle Towns which included the Valley Towns in southwestern North Carolina and northeastern Georgia and the Out Towns. There were some cultural and linguistic differences between these groups.

The Cherokee language belongs to the Iroquoian language family and glottochronology suggests that it diverged from other Iroquoian languages about 1800 BCE. Duane King writes:

“Structurally, Cherokee is a polysynthetic language. As in the case of German or Latin, units of meaning, called morphemes, are linked together and occasionally form very long words.”

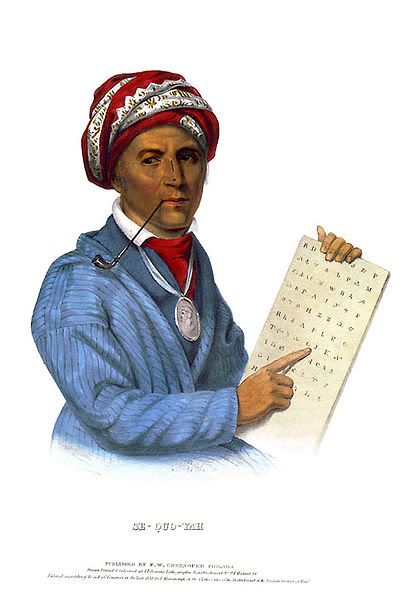

Sequoia

Sequoia was born about 1770 in a world in which Cherokee culture was being influenced by Euro-Americans. While many historians have speculated about the identity of his father—paternity is extremely important in European cultures—from a Cherokee perspective, the identity of his father is irrelevant. Cherokee culture was traditionally matrilineal which means that kinship was primarily from the mother. Fathers had no official relationship to their children because their children belonged to a different clan.

At some point in his youth he was apparently injured—some stories claim it was a hunting accident; others say he was wounded in battle—and this limited his mobility. He turned to silversmithing as a trade.

He observed the importance of writing among the Americans even though he was illiterate and did not speak English. Anthropologist Charles Hudson, in his book The Southeastern Indians, writes:

“With great wisdom, Sequoyah realized that one of the most important advantages of the whites over the Indians was their ability to put their words down on paper.”

By 1809, he had begun working on the development of a writing system for Cherokee. In his biography of Sequoia in the Encyclopedia of North American Indians, Raymond Fogelson writes:

“While his idea of writing was influenced by contact with whites, perhaps Sequoyah was also stimulated by the example of petroglyphs that abounded in Cherokee country.”

His efforts to create a Cherokee writing system were not always encouraged nor supported by others. In his book Who Was Who in Native American History: Indians and Non-Indians From Early Contacts Through 1900, Carl Waldman reports:

“His efforts met with opposition among tribal members, some of who suspected him of witchcraft.”

Sequoia’s efforts to create a Cherokee writing system apparently became an obsession. He let his farm go to waste, neglected his family, and was viewed as deviant in his behavior by Cherokee standards. Raymond Fogelson writes:

“His friends despaired of his obsession, and many suspected him of practicing sorcery. His wife eventually burned down his workshop in a fit of desperation.”

Initially, Sequoia had set out to develop a logographic writing system in which symbols would represent words or other units of meaning. By the time his workshop was destroyed he had developed about 1,000 symbols or characters. Raymond Fogelson writes:

“Following the loss of his workshop, Sequoyah claimed he had a better idea. Instead of a mark for each Cherokee word, he carefully set about listening to the sounds of the Cherokee language until he could differentiate distinctive sounds.”

In 1821, the Cherokee writing system was complete, and Sequoia introduced it to the Cherokee people.

The Syllabary

While historians and others commonly claim that Sequoia invented the Cherokee alphabet, this is not true: Sequoia’s Cherokee writing system uses a syllabary rather than an alphabet. In her Encyclopedic Dictionary of Archaeology, Barbara Ann Kipfer describes a syllabary this way:

“A system of written symbols used to represent the syllable of a language. Writing systems that use syllabaries include modern Japanese, Cherokee, the ancient Cretan scripts (Linear A, Linear B), and various Indian and cuneiform writing systems.”

In an alphabet, such as the one used for English, the letter c represents one sound and the letter a represents another and when the two are combined, ca, a syllable is formed. In a syllabary, ca would have its own symbol.

Most languages use about 80 symbols for the possible syllables in the language: in Cherokee there are 85. With regard to the Cherokee syllabary, Duane King writes:

“Seventy-eight of the eighty-five symbols in written Cherokee represent consonant-vowel combinations; the remainder represent the six vowels and the consonant s.”

Many of Sequoia’s 85 characters were borrowed from European alphabets, but the characters have phonetic values which are very different. In his chapter on Native American writing systems in the Handbook of North American Indians, Willard Walker writes:

“Some of Sequoya’s characters may have been borrowed from Greek or Cyrillic; others seem to have no precedent in other writing systems. Several closely resemble printed roman capital letters, although their phonetic values differ greatly from those of their roman counterparts, a fact that indicates that Sequoya was in no sense literate in any European language when he devised the syllabary.”

The Impact of Writing

With Sequoyah’s syllabary, the Cherokee quickly learned how to read and write in their own language. It is said that Sequoyah could gather a group of people together in the town square in the morning and that by sunset they would be reading and writing in their language. According to Raymond Fogelson:

“A Cherokee speaker can learn to read and write as soon as the eighty-five symbols are mastered, often after a few days of study.”

The idea of the Cherokees being able to write in their own language was opposed by many Christian missionaries and by the American government. One missionary wrote of the Cherokee language:

“I believe the less of it that is taught, or spoken, the better for the Indians. Their whole character, inside and out; language, and morals, must be changed.”

The American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, however, changed its approach with regard to using Indian languages and concluded that Indian languages should receive some attention. They found that the quickest way to teach Indian children English was to teach them to read in their own language first.

In 1825, The Cherokee Council earmarked $1,500 (one-fifth of their annual income) for the purchase of a press and type in Sequoia’s alphabet. While Sequoia’s alphabet made it possible for anyone who spoke the language to quickly learn to read and write the language, printing was difficult as there was no lead type for Sequoia’s alphabet. Samuel A. Worcester, a newly arrived missionary, made the arrangements for getting the type cast in Boston and for obtaining a press.

In 1828, the Cherokee Phoenix was started in Georgia under the editorship of Elias Boudinot (also known as Buck Wati, or Galagina). The weekly paper included articles in English as well as in Cherokee (using Sequoia’s alphabet).

The new paper was to include the following subjects:

(1) The laws and public documents of the Cherokee nation

(2) Accounts about Cherokee culture (“manners and customs”), the “arts of civilized life”, and notices of other Indian nations

(3) Interesting news of the day

(4) Articles to promote “literature, civilization, and religion among the Cherokee”

The paper also included extensive coverage of actions by Congress and by the State of Georgia which would impact the Cherokee. Historian Marion Starkey, in The Cherokee Nation, observes:

“Could the enemies of the Cherokee have foreseen the effects of the press on the Cherokees, they would have saved themselves much trouble by seizing it on its way through Georgia.”

The publication of the first edition of the paper, however, was delayed because no paper had been shipped with the press. A temporary supply of paper was then brought in by wagon from Knoxville, Tennessee.

In order to inform Cherokee citizens of the new Cherokee constitution, The Cherokee Phoenix published portions of it in both English and Cherokee.

In 1831, Elias Boudinot, the editor of the Cherokee Phoenix, had disagreements with Principal Chief John Ross regarding the paper’s editorial policy. Boudinot was a proponent of negotiating with the United States for the removal of the Cherokee to Oklahoma. The Cherokee national council, under the leadership of John Ross, closed the columns of the Cherokee Phoenix to any debate on the removal issue.

Elias Boudinot had also printed pieces which angered the Georgia Guard and twice he was arrested and threatened with a public whipping. The head of the guard felt that Boudinot didn’t have the talent to write the editorials and accused him of letting the missionaries write using his name. Boudinot resigned as editor and Elijah Hicks assumed management of the paper. In her book The Cherokees, Grace Steele Woodward reports:

“But, although he possessed depth of character and unquestioned integrity, and he was successful as a businessman, Hicks lacked Boudinot’s newspaper experience.”

In 1834, The Cherokee Phoenix ceased publication.

In addition to its political use, the Cherokee writing system also helped preserve Cherokee knowledge. Raymond Fogelson writes:

“Curers and Conjurers recorded in the syllabary many esoteric ceremonies for healing a wide range of native disorders, for divination, for love magic, for war and ball games, for sorcery, and for a variety of other specific purposes.”

Indians 101/201

Indians 101/201 is a series exploring American Indian histories, cultures, biographies, arts, and current concerns. Indians 201 is an expansion of an earlier essay.

Leave a Reply