For thousands of years, American Indian people in the Southwest farmed the land and built their villages, called pueblos by Spanish, with multi-story houses, plazas, and underground ceremonial chambers known as kivas. While the Pueblos are usually lumped together in both the anthropological and historical writings as though they are a single cultural group, they are linguistically and culturally divergent. The Zuni are not linguistically related to any of their Pueblo neighbors. The Zuni were among the first of the Pueblo Indians to come into direct contact with the Spanish in the sixteenth century.

The name Zuni is the Spanish corruption of the Keresan word Sunyi. The Native name for the pueblo is A’shiwi.

The Spanish began their invasion and conquest of the Southwest following their successes in Mexico where they found abundant gold and other treasures. The Spanish moved north from Mexico seeking to acquire gold from rumored (but imaginary) cities and to save souls for their god.

In 1539, Fray Marcos de Niza, a Franciscan monk adept in native languages, received permission to explore the southwest and to determine if the fabled riches actually existed. Esteván, the black slave who had been with an earlier expedition led by Cabeza de Vaca, accompanied him.

Near the present-day city of Hermosilla in Sonora, Mexico the expedition encountered some Pima Bajo Indians who gave them a warm reception and much food. They told the Franciscan of a valley with many large settlements where the people wore cotton (probably the Pima and Opata). The Spanish noticed that these Indians wore mica pendants and their pottery was made from mica-bearing clay. In asking about the Indians to the north, Fray Marcos assumed that the Indians were telling him that these people had pendants and vessels made of gold and silver.

Dennis Reinhartz and Oakah Jones, in their essay in North American Exploration. Volume 1: A New World Disclosed, write:

“Many of these stories probably contained grains of truth, but by this time the Indians, especially those of northern Mexico, had learned to tell the Spanish invaders whatever they wanted to hear.”

After hearing the stories about what he assumed were the Seven Cities of Cibola (the fabled cities of silver and gold), Fray Marcos sent Esteván with an advance party to investigate this possibility. They followed a well-established trading route that connected northern Mexico with the American Southwest. Esteván reached as far north as the Zuni pueblo of Hawikuh in present-day New Mexico, where he was killed.

While Marcos never reached Zuni, he still described it as being bigger than Mexico City. In his report in the Handbook of North American Indians, Richard Woodbury writes:

“Fray Marcos glimpsed Hawikuh from a distant mesa and returned south, but his report was sufficient reason for a large-scale exploring expedition the next year under Francisco Vásquez de Coronado.”

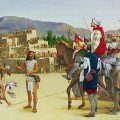

The following year, 1540, Francisco Vásquez de Coronado began his journey north from Mexico seeking the Seven Cities of Cibola described by Fray Marcos. He took with him a force of 330 Spaniards (most of whom are mounted soldiers) and 1,000 native allies. The expedition started with 552 horses and 2 mares. The seven cities proved to be six Zuni villages: Hawikuh, Kianawa, Kwakina, Halona, Matsaki, and Kiakima.

While Coronado marveled at the Zuni houses, he commented:

“I do not think that they have the judgment and intelligence needed to be able to build these houses in the way in which they are built, for most of them are entirely naked.”

The Spanish arrived at Hawikuh at the culmination of the summer solstice ceremony. The Zuni priests drew a line of white cornmeal across the ground to inform the Spanish that they were not to enter the village. The Spanish ignored the warning. The Zuni met the Spanish explorers with hostility, attacking them before they were in sight of Hawikuh. Using signal fires, the Zuni signaled the Spanish presence to others in the region.

The Spanish, needing food desperately, attacked the village and after fierce fighting managed to capture it. Dennis Reinhartz and Oakah Jones report:

“After a fierce hour-long battle, in which Coronado, marked as the leader by the Indian defenders, sustained several wounds, the pueblo and its valuable food stores fell to the Spanish.”

The Zuni fled to their stronghold on Thunder Mountain.

In 1542, the Spanish under Francisco Vásquez de Coronado stopped at Hawikuh on their way back to Mexico. They left behind several Mexican Indians from their party.

In 1544, Spanish authorities held an inquiry into alleged abuse of Native peoples by the members of the expedition of Francisco Vásquez de Coronado. The allegations included sexual abuse of Indian women, the execution of an Indian guide in Kansas, and not paying Indians for food and goods. In the inquiry there is an assumption of Spanish superiority. Historian Richard Flint, in an article in the New Mexico Historical Review, writes:

“Attitudes of unquestioned superiority of all European and Christian things, persons, and forms over their American counterparts were the root cause of pervasive hostility between the expedition and the native peoples it sojourned among, be they Opata or Zuni, Tiquex or Teya.”

As a result of the inquiry, one member of the expedition was punished for violence against the Indians.

In 1581, Francisco Sanchez Chamuscado led a small party of priests and soldiers—28 in all: 3 friars, 9 soldiers, and 16 servants—into Pueblo country in the southwest. The Spanish were looking for minerals to mine and women and children who could be enslaved to work as translators. At Zuni they had a cordial reception.

In 1583, Spanish conquistador Antonio de Espejo and his soldiers took formal possession of Zia Pueblo and the land around it for the King of Spain. The party then moved to El Morro and then to the Zuni pueblos. At Zuni, they find that the Mexican Indians left behind by the 1542 Coronado expedition are still there.

In 1598, Juan de Oñate officiated over the Act of Obedience and Vassalage ceremony that became the Spanish instrument of authority over the Zuni. The Indians were told that the Spanish had come to bring them knowledge of God and the Spanish King, on which depended the salvation of their souls and the continuation of the security of their homes. According to the official proceedings:

“Wherefore they should know that there is only one God, creator of heaven and earth, rewarder of the good, whom He takes to heaven, and punisher of the wicked, whom He sends to hell. This God and lord of all had two servants here on earth through whom He governed.”

The Zuni were also informed that the world was ruled by the Pope and by the Spanish King, who was described as “sole defender of the church, king of Spain and the Indies.”

Indians 101

Indians 101 is a series exploring American Indian histories, cultures, and current concerns.

Leave a Reply