pow-wow-women-eastcountymagazine.org

pow-wow-women-eastcountymagazine.org

Welcome to WOW2 — Special Edition!!

WOW2 is a twice-monthly sister blog to This Week in the War on Women, but this is a Special Edition. The WOW2 — Late November blog will post next week.

The purpose of WOW2 is to learn about and honor women of achievement, including many who’ve been ignored or marginalized in most of the history books, and to mark moments in women’s history. It also serves as a reference archive of women’s history. There are so many more phenomenal women than I ever dreamed of finding, and all too often their stories are almost unknown, even to feminists and scholars.

These trailblazers have a lot to teach us about persistence in the face of overwhelming odds. I hope you will find reclaiming our past as much of an inspiration as I do.

This Week in the War on Women

just posted, so be sure to go there next and catch up on the latest dispatches from the frontlines: www.dailykos.com/…

The regular editions of WOW2 are organized chronologically. But many cultures do not have our obsession with Greenwich Mean Time and the Gregorian calendar, so how to include these outstanding women when their day or year of birth is measured differently? My goal has always been to find and celebrate as many women of accomplishment from as many cultures, religions, timelines and walks-of-life as possible.

‘Indian’ and ‘Native American’ are really white people words which treat the incredibly rich and diverse cultures of the first known human inhabitants of the ‘Americas’ as if they were all the same. That the word ‘Indian’ has stuck for over 500 years seems especially strange to me — Christopher Columbus assumed he had reached islands off the coast of India, and his mistake has caused endless confusion.

But I’m also guilty of imposing order arbitrarily — the names are more-or-less alphabetical and mostly in English, and Gregorian calendar dates have been used when available to help explain when things happened. So my own cultural bias in organizing material is showing.

This WOW2 ‘Special Edition’ highlights just a few fascinating women of the First Peoples. There are so many more.

Seneca corn husk mask

Seneca corn husk mask

Queen Alliquippa, a Seneca tribal leader during the early part of the 18th century in what is now Pennsylvania. The Senecas were part of the Iroquois League, also known as the Six Nations: Cayuga, Mohawk, Onondaga, Oneida, Seneca, and Tuscarora.

In 1701, she, with her husband and infant son, traveled from the Conestoga Valley to Wilmington DE to say good-bye to William Penn, who was about to sail home to England. By the 1740s, she was the leader of a Seneca band living along the three rivers – the Ohio, the Allegheny, and the Monongahela – near what is now Pittsburgh. In the words of another Seneca chief of the era, “Women have great influence on our young warriors,” he said. “It is no new thing to take women into our councils, particularly among the Seneca.” This was becoming increasingly true in the mid-1700s, as frequent skirmishes depleted the ranks of the male warriors, and the tribal systems among the Iroquois confederation began to break down. In 1748, Conrad Weiser, Pennsylvania’s ambassador to the Indian nations, traveled through the area on his way to a council meeting. When she found that Weiser had gone by without stopping in her village, she sent word to him demanding that he come and pay tribute. Not wishing to offend her, he quickly complied only to be further chided for not bringing enough gunpowder to give to her village. Unlike many of her contemporaries, who sided with whoever offered the best deal at the time, Aliquippa remained fiercely loyal to the British throughout her life. When the French explorer Celeron came down the Allegheny River in 1749 to claim the Ohio country for the king of France, Aliquippa refused to receive him in her village. His journal entry of the thwarted visit hints again at her imperious attitude. “The Iroquois [speakers of an Iroquian dialect] inhabit this place and it is an old woman of this nation who governs it,” he wrote. “She regards herself as a sovereign. She is entirely devoted to the English.”

20-year-old Major George Washington, acting as an ambassador from the British crown to French officials and Indian leaders, visited her in December 1753: “As we intended to take horse here [at Frazer’s Cabin on the mouth of Turtle Creek], and it required some time to find them, I went up about three miles to the mouth of the Youghiogheny to visit Queen Aliquippa… I made her a present of a match-coat and a bottle of rum, which latter was thought much the better present of the two.”

Queen Alliquippa was a key ally of the British leading up to the French and Indian War. She and Washington crossed paths again in July 1754, when he was under siege at Fort Necessity. Aliquippa and her son Kanuksusy, with warriors from her band, traveled to Fort Necessity to hole up with Washington’s small troop at the fort. Washington, now a militia lieutenant colonel, wanted to hold a small ceremony honoring the queen for her loyalty and service to the British cause. Begging ill health, Aliquippa asked that her son be honored in her place. Washington agreed, and the ceremony went on. As part of the event, Kanuksusy was given the English name Colonel Fairfax, after one of Washington’s Virginia benefactors. After the fall of Fort Necessity on July 4, 1754, Aliquippa and the remainder of her clan moved onto the fortified homestead of frontier trader George Croghan. That place, called Augswich, was where the tired Seneca leader, then probably over 80 years old, lived out her last few months. Queen Aliquippa died there on December 23, 1754

Rita Pitka Blumenstein was born in 1936, a month after her father died, while her mother was out in a fishing boat. Her heritage is Yup’ik. She became the first certified traditional doctor in Alaska, and works for the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium. Blumenstein has been a member of the International Council of 13 Indigenous Grandmothers — a group of spiritual elders, medicine women and wisdom keepers — since its founding in 2004

“The past is not a burden; it is a scaffold which brought us to this day. We are free to be who we are – to create our own life out of our past and out of the present. We are our ancestors. When we can heal ourselves, we also heal out ancestors, our grandmothers, our grandfathers and our children. When we heal ourselves, we heal Mother Earth.” — Rita Pitka Blumenstein

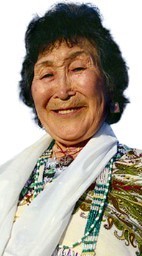

Beth Brant, Degonwadonti (1941-2015), was a Mohawk writer, one of the first prominent Native American lesbian writers. She was first published as part of Sinister Wisdom in 1984, and edited the anthology Gathering of Spirit: A Collection by North American Indian Women in 1988, the first anthology of Native American women’s writing edited by a Native American woman. She published several poetry and essay collections on topics such as Mohawk identity, queerness, and feminism, including Mohawk Trail (1985), Food and Spirits (1991); and Writing as Witness: Essay and Talk (1994). She also edited an oral-history anthology of Mohawk elders titled I’ll Sing ‘til the Day I Die: Conversations with Tyendinaga Elders.

LaDonna Brave Bull Allard is a Standing Rock Sioux activist, tribal historian and a leader in the fight against the Dakota Access Pipeline. In April 2016, she founded the Sacred Stone Camp, part of the #NoDAPL movement, which has grown to be one of the most powerful and widely supported Indigenous rights movements in recent decades.

Buffalo Calf Road Woman — In 1876, the Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho people were defending their sovereignty, their land, and their lives against the United States. The Rosebud and Little Bighorn battles proved the tribes’ military strength but ultimately had tragic consequences for the victors. Buffalo Calf Road Woman fought alongside her brother and husband at both battles in defense of Cheyenne freedom.

June, 1874, Cheyenne and Lakota warriors fought U.S. Brigadier General George Crook at the Rosebud, Buffalo Calf Road Woman, her husband Black Coyote, her brother, Comes In Sight were with them. When the horse of Comes in Sight was shot and he fell, his sister rode into the battle’s heart, helping him cling to her horse as she carried him to safety. The battle was a stand-off, both sides left the field. Most of the Lakotas and Cheyennes raced to join those camped on the Little Big Horn.

Eight days after Rosebud, Custer’s regiment attacked the encampment. Most of the women took their children away from the fighting, but Buffalo Calf Road Woman and some others some with the warriors, singing “strong heart’ songs as they watched for fallen or injured men.

Buffalo Calf Road Woman was the only woman with a gun, which she fired at the enemy soldiers. She also rescued a Cheyenne warrior who had lost his horse, taking him up behind her to ride for the river where spare horses were kept.

But the U.S. Army hunted down the Cheyenne who took to the hills after the battle, and in 1877, facing starvation, they surrendered, only to be marched 1500 miles to Fort Reno in Indian Territory (now Oklahoma). In the fall of 1878, three hundred Cheyenne escaped and headed north toward home. They split into two groups, Buffalo Calf Road Woman’s family continuing north following Chief Little Wolf. When Black Coyote killed a soldier, the family was captured and taken to Fort Keogh in Montana. Buffalo Calf Road Woman died from diphtheria in the winter of 1879. In his grief, Black Coyote committed suicide.

Today Cheyenne people still call the Rosebud battle site “Where the Girl Saved Her Brother.”

Brenda Child is a Red Lake Ojibwe scholar and professor who studied histories of boarding schools, Ojibwe women’s activism, Indigenous education, and Ojibwe labor, among other topics. Her debut book, Boarding School Seasons: American Indian Families, 1900 to 1940, used letters between parents and their children in boarding schools to explore the deep emotional impact of these assimilationist institutions. In her 2012 book, Holding the World Together: Ojibwe Women and the Survival of Community, she outlines the profound ways that Ojibwe women have contributed to strengthening their communities for centuries—from helping to mediate between tribes and European fur traders to organizing to ameliorate urban Indian poverty after World War II.

Yvonne Chouteau (March 7, 1929 – January 24, 2016) was a member of the

Shawnee Tribe, and one of the “Five Moons,” the Native American prima ballerinas of Oklahoma. In 1943, she became the youngest dancer ever accepted to the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, where she worked for fourteen years.

After the birth of their first child, she returned to her home state, and with her husband, Miguel Terekhov, organized the Oklahoma City Civic Ballet (now Oklahoma City Ballet.) In 1962, they founded the first fully accredited university dance program in the United States, the School of Dance at the University of Oklahoma.

Chrystos is a Menominee two-spirit poet and activist. Their poetry explores issues of colonialism, genocide, violence against Native people, queerness, street life, and more. Their work has been featured in various anthologies, including This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color, edited by Cherrie Moraga and Gloria Anzaldúa. They are the author of five poetry anthologies. Chrystos’s book No Vanishing, published in 1998, was a best seller. Throughout their poetry, they often include cliches, plays on words, and rhymes as a refusal to separate spoken word and oral tradition from poetry.

Two-Spirit (also two spirit or, occasionally, twospirited) is a modern, pan-Indian, umbrella term used by some indigenous North Americans to describe certain people in their communities who fulfill a traditional third-gender (or other gender-variant) role in their cultures. This is not “LGBT Native.” The term and identity of two-spirit “does not make sense” unless it is placed in within the context of a Native American or First Nations framework and traditional cultural understanding. The term was adopted by consensus in 1990 at an Indigenous lesbian and gay international gathering to encourage the replacement of the outdated, and now seen as inappropriate, anthropological term berdache. It is not so much about whom one is sexually interested in, or how one personally identifies; rather, it is a sacred, spiritual and ceremonial role that is recognized and confirmed by the Elders of the Two Spirit’s ceremonial community.

The Dann Sisters, Mary Dann (1923–2005) and Carrie Dann (born c. 1932), Western Shoshone elders who are spiritual leaders, ranchers, and cultural, spiritual rights and land rights activists.

The 1863 Treaty of Ruby Valley with the Western Shoshone allowed U.S. citizens safe passage through Western Shoshone lands, defined in the treaty as a large portion of Nevada and 4 other states; protected access by the Pony Express; permitted gold mining; and gave the U.S. right-of-way for future construction of railroads. In exchange, the federal government was to pay annuities in cash or goods equaling $5000 for 20 years, but only the first payment was made.

Since then, the U.S. Congress has consistently passed legislation giving the government much of the Western Shoshone land, now held for “resource management” by the BLM (Bureau of Land Management) and the Department of Energy (DOE). The DOE has conducted over 100 atmospheric nuclear tests, and detonated nearly 1000 bombs in the territory.

The Western Shoshone filed suit decades ago trying to reclaim their land. In 1962 the now defunct Indian Claims Court (which expired in 1978) ruled the Shoshone had lost control of their land due to settler encroachment, and they were not entitled to any claim from the US government, but in 1979 the Indian Claims Commission awarded a $26 million land claim settlement to the Western Shoshone. Part of the case went to federal courts for litigation. The US Supreme Court ruled in 1985 that the Shoshone land claims were extinguished by this financial settlement. The Shoshone refused to take the money, since 80% of the Shoshone who voted on the issue were against accepting the financial settlement; instead, they asked the US to respect the terms of the 1863 treaty. Some Shoshone have wanted the tribe to take the money, and to distribute and invest it for the welfare of the tribe.

Since 1973, the Dann sisters conducted civil protest by ranching and refusing to pay grazing fees to the BLM to run their cattle outside their ranch on what they consider Shoshone land. They contended the U.S. government had taken the land illegally and not abided by the terms of its treaty.

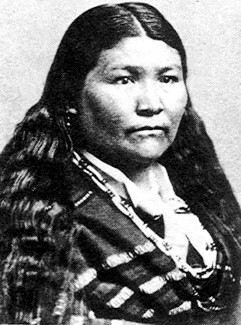

The Dann Sisters 1983

The Dann Sisters 1983

In 1982, Raymond Yowell was elected as chief of the newly organized Western Shoshone National Council, which has opposed accepting the settlement money (valued at $100 million in 1998, with

accrued interest) because it would extinguish their claims to the land.

In 1998, the BLM issued trespass notices to the Danns and Raymond Yowell, chief of the Western Shoshone Nation, ordering their removal of hundreds of cows and horses from public lands in Eureka County, Nevada. Carrie and Mary Dann filed a request for urgent action with the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination. They had been active in the movement to recover millions of acres of land in Nevada and bordering states that originally belonged to the Western Shoshone tribe.

The sisters persuaded the UN of their case. It ordered the US government to halt all actions against the Western Shoshone people, a mandate which has been mostly ignored.

Sarah Deer is a Muscogee lawyer, professor, and advocate who has worked for victims rights and sexual violence prevention for decades. She was an instrumental leader in the 2013 reauthorization of the Violence Against Women Act, which expanded tribal jurisdiction to prosecute non-Native perpetrators of domestic and sexual violence, as well as giving testimony credited with clinching the 2010 passage of the Tribal Law and Order Act. Deer coauthored, with Bonnie Claremont, Amnesty International’s 2007 report Maze of Injustice, documenting sexual assault against Native American women. Her book, The Beginning and End of Rape: Confronting Sexual Violence in Native America, is a collection of critical essays on violence against Native women. It gives a historical overview of the intersecting violences that contribute to the high rates of sexual violence against Native Americans today, from the history of rape and sex trafficking of Indigenous people to the destruction of tribal legal systems to protect their own citizens. Deer is a professor of law at William Mitchell College, and 2014 MacArthur fellow.

Louise Erdich (1954 – ) grew up in North Dakota, where her Chippewa mother and German-American father taught at a boarding school run by the Bureau of Indian Affairs. She describes the land as a place where the “earth and sky touch everywhere and nowhere, like sex between two strangers.” Erdrich is a mesmerizing story-teller, both in prose and poetry, adept at combining elements from both sides of her heritage with memorable imagery.

While better know for her novels, which include Love Medicine, The Beet Queen, and The Plague of Doves, she is also the author of children’s books, and three collections of poetry.

-.-.-.-.-

Windigo

For Angela

The Windigo is a flesh-eating, wintry demon with a man buried deep inside of it. In some Chippewa stories, a young girl vanquishes this monster by forcing boiling lard down its throat, thereby releasing the human at the core of ice.

-.-.-.-.-

You knew I was coming for you, little one,

when the kettle jumped into the fire.

Towels flapped on the hooks,

and the dog crept off, groaning,

to the deepest part of the woods.

Windigo — artist unknown

Windigo — artist unknown

-.-.-.-.-

In the hackles of dry brush a thin laughter started up.

Mother scolded the food warm and smooth in the pot

and called you to eat.

But I spoke in the cold trees:

New one, I have come for you, child hide and lie still.

-.-.-.-.-

The sumac pushed sour red cones through the air.

Copper burned in the raw wood.

You saw me drag toward you.

Oh touch me, I murmured, and licked the soles of your feet.

You dug your hands into my pale, melting fur.

-.-.-.-.-

I stole you off, a huge thing in my bristling armor.

Steam rolled from my wintry arms, each leaf shivered

from the bushes we passed

until they stood, naked, spread like the cleaned spines of fish.

-.-.-.-.-

Then your warm hands hummed over and shoveled themselves full

of the ice and the snow. I would darken and spill

all night running, until at last morning broke the cold earth

and I carried you home,

a river shaking in the sun.

-.-.-.-.-

Fidelia Hoscott Fielding (1827-1908) is considered the last speaker and preserver of the Mohegan Pequot language. She and her grandmother, Martha Uncas, conversed in their native dialect. Four diaries she left are now preserved and used in the reconstruction of the Mohegan and other related Indian languages. Fidelia called herself Dji’ts Bud dnaca, meaning “Flying Bird.” Following Fidelia’s marriage to William Fielding, she continued to live in the traditional Mohegan lifestyle. She remained something of a loner, and did not participate in the Green Corn Festivals or Church Ladies Sewing Society meetings. Fidelia was the last to live in the traditional style log dwelling. Fielding passed on many Mohegan traditions to Gladys Tantaquidgeon. From her, Gladys learned the stories of the Makiawisug, or Little People. She also gave Gladys a belt once belonging to Martha Uncas, with dome symbols of the 4 directions and spiritual force of the universe,and a beaded trail beside the tree of life which grows from Mother Earth to celestial beings

Sydney Freeland is a transgender Navajo filmmaker who uses film to combat stereotypes about Native Americans and highlight the experiences of queer and trans people. Her debut feature length film, Drunktown’s Finest, follows the lives of three young people living on the Navajo Reservation: a young father-to-be, a transgender woman who dreams of being a model, and a woman who was adopted by a white Christian family. The film’s name is a riff off an offensive ABC news segment that labeled Gallup, New Mexico, as “Drunk Town, USA.” Freeland also directed web series Her Story, which revolves around queer and trans women, and was nominated for an Emmy.

Glory of the Morning (died c. 1832) was the first woman ever described in the written history of Wisconsin, and the only known female chief of the Hocąk (Winnebago) nation. She was the daughter of the tribal chief, a member of the Thunderbird Clan who lived in a large village on Doty Island (now in Menasha, Winnebago County, Wisconsin)

Sometime before 1730, a small force of French troops under the command of Sabrevoir de Carrie visited the Hocągara and established cordial relations. Carrie resigned his commission, became a fur trader, and married Glory of the Morning. Glory of the Morning’s marriage seems to have enhanced her status, as her husband is remembered very favorably in the Hocąk oral tradition, “in his affairs he was most emphatically a leader of men.” They had two sons and a daughter.

Glory of the Morning firmly allied herself with her husband’s people, and fought neighboring tribes for 7 years before there was peace. But when warfare renewed with the Illini, her braves fell upon the Michigamea and the Cahokia.

During the war between France and Great Britain in 1754, Hocak warriors attacked the English settlements far to the east. However, when the British overcame the French, Glory of the Morning established friendly relations with them, refusing to tread the war path of Pontiac.

In 1766, Captain Jonathan Carver of Connecticut in the service of the Crown, paid a visit to her village, giving this account of her:

On the 25th [of September] I left the Green Bay, and proceeded up Fox River, still in company with the traders and some Indians. On the 25th I arrived at the great town of the Winnebagoes, situated on a small island just as you enter the east end of Lake Winnebago. Here the queen who presided over this tribe instead of a Sachem, received me with great civility, and entertained me in a very distinguished manner, during the four days I continued with her…

The Queen sat in the council, but only asked a few questions, or gave some trifling directions in matters relative to the state…She was a very ancient woman, small in stature, and not much distinguished by her dress from several young women that attended her. These her attendants seemed greatly pleased whenever I showed any tokens of respect to their queen, particularly when I saluted her, which I frequently did to acquire her favour. On these occasions the good old lady endeavoured to assume a juvenile gaiety, and by her smiles showed she was equally pleased with the attention I paid her. …

Having made some acceptable presents to the good old queen, and received her blessing, I left the town of the Winnebagoes on the 29th of September …

Nothing more is heard of her until Arthur and Juliette Kinzies visited her in 1832. She had lived to an unheard of age. Mrs. Kinzie paints a portrait of her:

There was among their number, this year, one whom I had never before seen—the mother of the elder Day-kau-ray. No one could tell her age, but all agreed that she must have seen upwards of a hundred winters. Her eyes dimmed, and almost white with age—her face dark and withered, like a baked apple—her voice tremulous and feeble, except when raised in fury to reprove her graceless grandsons, who were fond of playing her all sorts of mischievous tricks, indicated the very great age she must have attained. She usually went upon all fours, not having strength to hold herself erect…

She must have died soon afterwards. Hocąk lore says that when she was out among the pines, an owl, a bird of ill omen, perched nearby and called her name. That night, wrapped in her furs with a smile on her face, she died. There was a raging blizzard that night, but the rare sound of thunder was heard, as if the Thunderbirds of her clan were calling her home.

Mishuana Goeman is a member of the Tonawanda band of Seneca, whose work

focuses on settler colonialism, gender violence, and Native women’s cultural production, giving a feminist perspective to colonial spatial definitions of Native land (national or reservation borders) and bodies, analyzing how colonialism attempts to impose a new spatial reality on Indigenous people. Author of Mark My Words: Native Women Mapping Our Nations, she is an Associate Professor of Gender Studies, Chair of the American Indian Studies Interdepartmental Program and Associate Director of the American Indian Studies Research Center at UCLA

Joy Harjo (1952 – ) is a poet, musician, author, activist and teacher. Born in Tulsa, Oklahoma, she is member of the Mvskoke tribe, and a highly influential figure in the second wave of the artistic Native American Renaissance. She says: “The name Harjo means ‘so brave you’re crazy.” She studied at the Institute of American Indian Arts, earned her undergraduate degree at the University of New Mexico, and an MFA from the University of Iowa’s Creative Writing Program. Harjo is the recipient of many awards, including the 2009 Eagle Spirit Achievement Award and the Wallace Stevens Award in Poetry by the Academy of American Poets. Her memoir, Crazy Brave, won a 2013 American Book Award.

-.-.-.-.-

Eagle Song

-.-.-.-.-

To pray you open your whole self

To sky, to earth, to sun, to moon

To one whole voice that is you.

And know there is more

That you can’t see, can’t hear;

Can’t know except in moments

Steadily growing, and in languages

That aren’t always sound but other

Circles of motion.

Like eagle that Sunday morning

Over Salt River. Circled in blue sky

In wind, swept our hearts clean

With sacred wings.

We see you, see ourselves and know

That we must take the utmost care

And kindness in all things.

Breathe in, knowing we are made of

All this, and breathe, knowing

We are truly blessed because we

Were born, and die soon within a

True circle of motion,

Like eagle rounding out the morning

Inside us.

We pray that it will be done

In beauty.

In beauty.

-.-.-.-.-

Suzan Shown Harjo is a policy advocate and writer of Cheyenne and Hodulgee Muscogee heritage. She served as the congressional liaison on Indian Affairs for President Jimmy Carter and, in the late 1980s, as the president of the National Congress of American Indians, an advocacy organization that unites tribal representatives from across the nation. She was involved with the passage of several important laws pertaining to Native American rights, including the American Indian Religious Freedom Act (1978), the National Museum of the American Indian Act (1989), and the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (1990). She received the Presidential Medal of Honor from President Barack Obama in 2014.

Debora Iyall (1954 — ) a member of the Cowlitz tribe; artist, printmaker and art instructor; former lead singer for the new wave band Romeo Void. She was born in Soap Lake WA, and got her surname when her family adopted their ancestor Iyallwahawa’s “first” name written at the time as Ayiel.

Corn Springs

Corn Springs

Betty Mae Tiger Jumper (1922-2011) was born in Indiantown, Florida, one of the few remaining Seminole communities in the South, to a Seminole mother and a French trapper father, who left the family when she was too young to remember much about him. Since Jumper and her brother were mixed race, there were some Seminoles who believed that children of such unions, forced or consenting, should be put to death. A group of men came to the family home, but her great uncle, Jimmie Gopher, a Seminole Nation leader who had converted to Christianity and worked with Oklahoma missionaries, confronted the men. He got the men to leave, and helped his niece to move away from the Nation, to Dania, Florida. Jumper was refused entry to both the black and white segregated schools, so she went to a Native American boarding school in Cherokee, North Carolina, the first known Florida Seminole to read and write in English, and graduate from high school.

She was accepted at the Kiowa Indian Hospital in Oklahoma, and trained as a nurse. Returning to her community, she became a public nurse and healthcare advocate. Jumper was the first woman to serve on the Seminole council, which her efforts helped in obtaining federal recognition in 1957. She was elected to the Board of Directors, and was the first, and to date the only, Seminole woman to be elected chair of the Nation Council. During her four-year term, she increased the community’s financial surplus from forty dollars to half a million. Jumper began the Nation’s first newspaper, now called the Seminole Times.

Jumper Biography for Children

Jumper Biography for Children

One of two women appointed by President Nixon to the National Congress on Indian Opportunity, she used this position to found the United South and Eastern Tribes, a lobbying group representing the Choctaw, Miccosukees, Cherokee and the Seminoles, which has expanded to include twenty-four more Nations.

In her later years, she was a Nation storyteller, recounting Seminole history to children, and wrote books, including And With The Wagon Came God’s World and Legends of the Seminoles. She was one of the last matriarchs of the Snake Klan when she died at age 88.

Hawaiian nationalist and activist Haunani Kay-Trask is also a writer and educator. She is connected to the Piʻilani line on her maternal side and the Kahakumakaliua line on her paternal line. As an advocate for Indigenous Hawaiian rights, she is a vocal critic of the U.S. military presence and tourism industry in Hawaii. Her book, From a Native Daughter: Colonialism and Sovereignty in Hawaii, explores the ongoing discrimination and denial of rights to Native Hawaiians. In the book, she analyzes Hawaiian activism against U.S. imperialism—from the advocacy of Ka Lahui Hawai’i, a Native Hawaiian self-governing organization, to on-campus organizing by Indigenous students at the University of Hawaii.

Loretta Kelsey (1948 — ) is a “language keeper,” the only living native speaker fluent in Elem Pomo, an 8,000-year-old dialect spoken by a people who once flourished along the shores of Clear Lake (Lake County CA). Handed down orally and never written, the language has nearly vanished, but she is doing everything she can to make sure the ancient words do not die with her. More than half of the over one hundred native California tongues have already disappeared. A documentation project for the language, which had not been written down, started in 2003 at the Big Valley Rancheria.

Although Kelsey is teaching younger speakers, it is not clear if the language can be maintained based on her knowledge, as she is having trouble keeping her fluency because no one else can really carry on a conversation with her. But she is working with her nephew, Robert Geary, and Professor Emeritus Leanne Hinton, one of the nation’s top Pomo language researchers. In addition to conducting language camps, Kelsey is writing a dictionary and a phrase handbook, with help from Hinton and some of her colleagues.

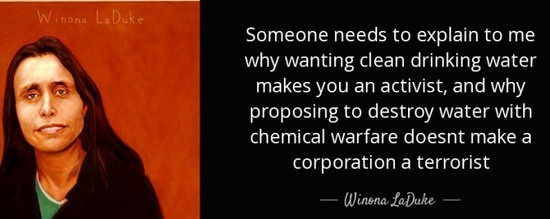

Winona LaDuke (1959 — ) is an Ojibwe environmentalist, economist, and writer, known for her work on tribal land claims and preservation, as well as sustainable development. In 1996 and 2000, she ran for U.S. vice president as the Green Party nominee.

Winona (meaning “first daughter” in Dakota language) La Duke is the daughter of Vincent (now known as Sun Bear) LaDuke, from the Ojibwe White Earth Reservation in Minnesota, and Betty Bernstein, a Jewish woman from the Bronx NY. She was born in Los Angeles, and attended Harvard, where she became part of a larger group of Indian activists, graduating in 1982 with a degree in rural economic development.

When LaDuke moved to White Earth she did not know the Ojibwe language, and was not easily accepted. While working as the principal of the local reservation high school she completed research for her master’s thesis on the reservation’s subsistence economy and became involved in local issues. She completed an M.A. in Community Economic Development through the distance-learning program of Antioch University.

artist not credited

artist not credited

In 1985 she helped found the Indigenous Women’s Network. She is the executive director of Honor the Earth, and has worked with the group Women of All Red Nations to publicize American forced sterilization of Native American women.

Currently LaDuke is at Standing Rock for the Dakota Access Pipeline protests, participating at the resistance camps in North Dakota as well as speaking to the media. In a September 12, 2016, interview with Amy Goodman from Democracy Now!, LaDuke said:

“…I feel like I’ve been like the Standing Rock switchboard, the travel guide, for the past two weeks. You know, everybody hits me up on Facebook, calls me up: ‘Hey, LaDuke, I want to bring out this. I got some winter coats. You know, what should I do?’

So, a lot of people are coming here, united…I’ve seen people from the—you know, from Wounded Knee in 1973. I’ve seen people I worked with in opposing uranium mining in the Black Hills in the 1970s and ’80s… I mean, I’ve been at this a while, it’s like Old Home Week out here. I’ve seen people from Oklahoma that opposed the Keystone XL pipeline, and Nebraska…The tribal chairman of Fond du Lac is here, and a whole host of Native and non-Native people. And there are a lot of people that just do not believe that this should happen anymore in this country, that are very willing to put themselves on the line, non-Indian people, you know, as well as tribal members, and they are here. And it is a beautiful place to defend.”

Barbara McAlister (1941 — ) is an enrolled member of the Cherokee Nation, a descendant of Old Tassel, and half German/Cherokee through her mother. An internationally acclaimed mezzo-soprano opera singer, she also paints in the Bacone style, a flat intertribal Modernist school using traditional elements from Prairie, Plains, and Eastern tribes.

For her dedication to promoting the Cherokee language, she was awarded the Cherokee Medal of Honor from the Cherokee Honor Society.

Beatrice Medicine (1923-2005) was a Standing Rock Sioux, a prominent Native American anthropologist, whose writing was focused particularly on Native women. Her book, The Hidden Half: Studies of Plains Indian Women (edited with Patricia Albers), was one of the first studies on the lives of Native American women. As well as working as a professor and scholar, she also served on her home reservation school board and taught classes at Native American Educational Services in Chicago, Illinois, a college dedicated to educating nontraditional students on community building. Her broad expertise made her a frequent expert witness in trials related to Native American issues, including the trial of the Wounded Knee occupants in 1973.

The Nampeyo Pottery Dynasty:

Founder: Nampeyo of Hano (1859 –1942) was a Hopi-Tewa potter who lived on the Hopi Reservation in Arizona. Her Tewa name was also spelled Num-pa-yu, meaning “snake that does not bite”

Nampeyo of Hano

Nampeyo of Hano

Nampeyo was born on First Mesa in the village of Hano, also known as Tewa Village which is primarily made up of descendants of the Tewa people from Northern New Mexico who fled west to Hopi lands about 1702 for protection from the Spanish after the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. Her mother, White Corn was Tewa; her father Quootsva, from nearby Walpi, was a member of the Snake clan. According to tradition, Nampeyo was born into her mother’s Tewa Corn clan.

She used ancient techniques for making and firing pottery and used designs from “Old Hopi” pottery and sherds found at 15th-century Sikyátki ruins on First Mesa. Her artwork is in collections in the United States and Europe, including many museums like the National Museum of American Art, Museum of Northern Arizona, and the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University.

Nampeyo and her husband traveled to Chicago in 1898 to exhibit her pottery. Between 1905 and 1907, she produced and sold pottery at the Grand Canyon lodge owned by the Fred Harvey Company. She exhibited in 1910 at the Chicago United States Land and Irrigation Exposition.

One of her famous patterns, the migration pattern, represented the migration of the Hopi people, with feather and bird-claw motifs. An example is a 1930s vase in the collection of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C.

Fannie Nampeyo (1900–1987), daughter of Nampeyo of Hano, was the youngest, and perhaps the most famous, of her three daughters. She was born in the Hopi-Tewa Corn Clan home atop First Mesa. Fannie was initially given the name Popongua or Popong-Mana (meaning “Picking Piñons”) by the older women of her father Lesou’s family, and either missionaries or health-care workers later gave her the name “Fannie.”

Fannie’s version of her mother’s migration pattern

Fannie’s version of her mother’s migration pattern

In the early 1920s she married Vinton Polacca. She increasingly worked with her mother Nampeyo, whose eyesight was diminishing due to trachoma. Fannie helped her mother with pottery painting and decorating, and also assisted her father with polishing. Early works created by Fannie and her mother were signed simply “Nampeyo” by Fannie, since Nampeyo could not read or write, but later they began signing pieces made together as “Nampeyo Fannie”. Pieces made solely by Fannie were signed “Fannie Nampeyo” and usually included a drawn corn symbol.

Elva Nampeyo (1926-1985), was Fannie’s daughter and Nampeyo’s granddaughter, who watched her grandmother as a child, and was taught the potter’s art by her mother. Her children Neva, Elton, Miriam, Adelle and Iris are all potters. They sign their work with their first names followed by “Nampeyo” and an ear of corn. Several of their children are also potters.

The wife of Bald Head Knife Butcher was a Pawnee woman in the 19th century. The storytellers say she was a tall woman with a deep voice. Her children were: War Cry (oldest son); High Noon; Noted Fox; Victory Call’s 2nd Wife White Woman’s Older Sister; and White Woman 3rd Wife. When her village was attacked by the Ponca and Sioux, the Pawnee men tried to run away. She grabbed a war club and attacked the enemy, and shamed the men into taking action. From that day, she was called Old-Lady-Grieves-the-Enemy (Ts tarahux-tu)

Natural Falls OK

Natural Falls OK

Elise Paschen (1959 — ) is an Osage Nation poet, and co-founder and co-editor of Poetry in Motion, a program which places poetry posters in subways and buses across the country. She is the daughter of the renowned prima ballerina Maria Tallchief.

Her three poetry collections are Houses: Coasts (1985), Infidelities (1996) and Bestiary (2009). She was the Executive Director of the Poetry Society of America (1988-2001), and has edited numerous anthologies, including Reinventing the Enemy’s Language: Contemporary Native Women’s Writings of North America (1997)

Dr. Paschen teaches in the MFA Writing Program at The School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

-.-.-.-.-

Wi’-gi-e

-.-.-.-.-

Anna Kyle Brown. Osage. 1896-1921. Fairfax, Oklahoma.

-.-.-.-.-

Because she died where the ravine falls into water.

Because they dragged her down to the creek.

In death, she wore her blue broadcloth skirt.

Though frost blanketed the grass she cooled her feet in the spring.

Because I turned the log with my foot.

Her slippers floated downstream into the dam.

Because, after the thaw, the hunters discovered her body.

-.-.-.-.-

Because she lived without our mother.

Because she had inherited head rights for oil beneath the land.

She was carrying his offspring.

The sheriff disguised her death as whiskey poisoning.

Because, when he carved her body up, he saw the bullet hole in her skull.

Because, when she was murdered, the leg clutchers bloomed.

But then froze under the weight of frost.

During Xtha-cka Zhi-ga Tze-the, the Killer of the Flowers Moon.

I will wade across the river of the blackfish, the otter, the beaver.

I will climb the bank where the willow never dies.

-.-.-.-.-

Audra Simpson is a Mohawk anthropologist from the Kahnawá:ke community in Quebec, She is an associate professor of anthropology at Columbia University where she has taught since 2008. Simpson’s research focuses on the politics of recognition—particularly, the Kahnawà:ke Mohawk struggles in asserting their legal and cultural rights across settler-imposed borders. Her book, Mohawk Interruptus: Political Life Across the Borders of Settler States, explores how Kahnawà:ke Mohawks maintain their sovereignty through traditional governance and a rejection of both U.S. and Canadian citizenship. Several indigenous studies scholars have acknowledged her book as a critical addition to scholarship on tribal community and national identity.

Jaune Quick–to–See Smith (1940 — ) is a contemporary artist. Her middle name “Quick-to-See” was given by her Shoshone grandmother in honor of her great grandmother Nellie Quick-to-See, an outstanding beadworker, and as a sign of her ability to grasp things readily. Born on the Salish and Kootenai Indian Reservation in Montana, her heritage is Salish-Kootenai, Métis-Cree, Shoshone-Bannock and French.

Her mother abandoned the family when she was two. Her father, an accomplished horse trainer and trader, moved around and traveled a lot, so she and her sister were in foster homes most of the time. She was bullied in school, but it was also the place she discovered art.

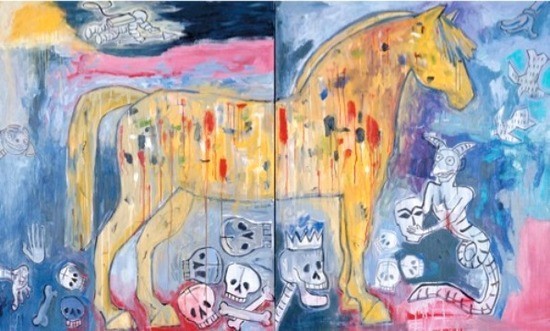

War Horse, 2002, Painting

War Horse, 2002, Painting

She now lives in New Mexico, and creates paintings and drawings that reflect her upbringing in a household where art and horses were equally important. As her work matured, she began to incorporate collage elements into her paintings, adding bits of calico and muslin fabric and wire mesh over which she lavished paint. Her work is displayed in numerous museums in Europe and South America, as well as the Museum of Modern Art, Whitney Museum of American Art, and Metropolitan Museum of Art, all in New York; Smithsonian Museum of American Art, Washington, DC; Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, MN; and the New Mexico Museum of Art, Santa Fe.

G. Anne Nelson Richardson (1965 —) is a Rappahannock woman, elected the first woman Chief to lead a tribe in Virginia since the 18th century. She is the fourth generation chief in her family.

In 1980, when she was only 15, she was elected as Assistant Chief to her father, then served in that position for the next eighteen years. In 1989, Richardson helped to organize the United Indians of Virginia, which was established as an inter-tribal organization with the all tribal Chiefs participating. She also served as the executive director of Mattaponi-Pamunkey-Monacan, Inc, a job training and placement program, beginning in 1991.

In 1998, Richardson was elected as Chief. Under her tenure, the Tribe purchased 119.5 acres (0.484 km2) to establish a land trust, retreat center, and housing development. The Tribe also built their first model home and sold it to a tribal member in 2001. The Rappahannocks are currently engaged in a number of projects ranging from cultural and educational to social and economic development programs.

In 2005, Richardson became chair of the Native American Employment and Training Council. She launched Restoring Nations International in 2006.

Winema ‘Toby’ Riddle (1846-1920) was a Modoc woman, who lived when the federal government was pressuring the Modoc and Klamath tribes to leave their homeland in the Cascade Range on the Oregon-California border, and move to a joint reservation near Klamath Lake in Oregon. As a child, she was named Nannooktowa (“strange child”) because of the reddish color of her hair. After she saved several children from drowning when their canoe caught in the rapids and overturned, she was known as Winema (“woman chief”). She refused to marry the Modoc man her father had chosen for her, marrying Frank Riddle, a white miner, instead. They were shunned by the tribe until her new husband met the obligations of a Modoc groom by giving several horses to his new father-in-law. Winema learned English from her husband, and became an interpreter and mediator between their two peoples. In 1852, the Modocs were wrongly blamed for an attack on a wagon train, and white vigilantes slaughtered 40 members of the tribe, including the father of her cousin, Kintpuash, who became the Modoc leader. He was called ‘Captain Jack’ by whites who couldn’t pronounce his name. In 1864, a peace treaty was signed, and the Modocs moved to the reservation with the Klamaths. The two groups clashed, and the Modocs left in 1865, came back in 1869, but left again in 1870. In 1872, President U.S. Grant ordered troops to force the Modocs back on the reservation, and the Modoc War began. After some bloody clashes, the Modocs retreated to a lava bed area which formed a stronghold, and Winema became the primary go-between, carrying messages back and forth. When negotiations broke down, the government commission proposed a face-to-face meeting. Winema was told that Kintpuash’s men were thinking about killing the commissioners, so she warned commissioners General Canby and Reverend Alfred Meacham, urging them to cancel the meeting. Her warning was ignored. The Modocs came to try to get better terms, but the commissioners quickly made it clear that only surrender would be accepted, so the Modocs opened fire, killing Canby and several others. Reverend Meacham was severely wounded, but Winema saved his life by shouting that soldiers were coming, and the Modocs fled. After two more months of fighting, the Modoc surrendered. ‘Captain Jack’ and other tribal leaders were put on trial before a U.S. military court. In spite of Winema’s testimony in which she tried to explain why the Modoc had fought, Kintpuash and four others were convicted and hanged. The remaining defenders of the lava beds were removed to Indian territory in Oklahoma. The Riddles went with the few Modocs who were allowed to remain, back to the Klamath Lake reservation. With the encouragement of Reverend Meacham, Winema and her husband went on a lecture tour across the United States to bring attention to the Modoc’s plight. In 1876, Alfred Meacham published Winema : “This book is written with the avowed purpose of doing honor to the heroic Wi-ne-ma who at the peril of her life sought to save the ill fated peace commission to the Modoc Indians in 1873. The woman to whom this writer is indebted, under God, for saving his life.” He also petitioned Congress to award her a military pension, which she received until her death, one of only a handful of women acknowledged by congress for her actions in wartime.

Anfesia Shapsnikoff (1901 – 1973) was an Aleut leader and educator born at Atka, Alaska in the Aleutian Islands. She was literate in three Unangan dialects and in both Russian and English. Small in stature, her appearance belied her vitality and strength

Anfesia Shapsnikoff had lived on Unalaska since she was a small child, probably in 1905. An island in the Aleutians, Unalaska had a small, mostly Aleut community which lived by traditional means well-suited to their environment.

Unalaska before WWII

Unalaska before WWII

During WWII, the U.S. military brought in white workers from the “lower 48,” who were completely unprepared for the isolation and harsh conditions of Unalaska, to build a military outpost on a nearby uninhabited island. The escalating number of workers and military personnel greatly disrupted the lives of the locals. Soon, the military wanted to take over Unalaska entirely.

Young men with money in their pockets and little to spend it on resulted in much drunkenness and brawling among the white workers and off-duty soldiers. Young Unangax women were being catcalled and accosted, but the white officers in charge considered the Unangax were the ones having a harmful effect on their men. A barbed-wire fence is put up to separate the white-occupied areas from “the natives.”

“The Unangax find themselves undesirables in a place they have inhabited for millenium—held responsible for the social ills visited upon them from outside…

June 3, 1942, almost six months to the day after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Japanese carrier-borne aircraft strike the military installations on Amaknak Island. June 4, Japanese fighter and bomber planes return. This time, several aircraft divert to Unalaska City to silence antiaircraft fire. The Church of the Holy Ascension is strafed, and a bomb blast shatters one end of the Indian Affairs Hospital. No one is harmed…

To address the wartime state of Unalaska, a “defense council” is formed of whites only. The Unangax number nearly one-half the population of Unalaska City, but are governed by whites and policed by whites. Granted full citizenship in 1867 at the purchase of Alaska from Russia, they have stood as Americans for 75 years, but are deemed “Indians” by the federal government—“wards” of the Department of Interior with no more say in the conduct of their lives than children…

July 18, 1942, the Unangax are told they have twenty-four hours to leave their homes. They may take only what they can carry—a suitcase, a trunk…they are allowed only clothing…no photograph albums, no keepsakes, no religious article—icon or holy lamp—no physical sign of the life they leave behind. Military police will search through their things before the bags are closed and locked. Dogs and cats must be left. Young children will carry what remains of their world in pillow sacks.

July 19, 1942, among the Unangax to be displaced are elders, pregnant women, and four infants one year old or less. No one is told where they will be taken, nor for how long. ..all Natives are to go, all persons with “as much as one-eighth native blood” in their veins. Since the mid-1700s, Caucasians and Natives in Unalaska have mixed their blood, but on 19 July 1942, a search is begun to determine who is “native” and who is not. A one-eighth “blood quantum test” will decide…

July 22, 1942, one hundred and thirty-seven Unangax are herded onto the steamer S.S. Alaska in Captains Bay. As they board ship, the purser impounds the hunting rifles and shotguns the Unangax men were ordered to bring. Some in command fear the Unangax have been so mistreated by the United States, they may take to arms for the Japanese.

– from Aleutian Voices – Forced to Leave, The National Parks Service/history

Anfesia Shapsnikoff Unangan teaches carrying basket weave c1960 AMHA B81.19.34

Anfesia Shapsnikoff Unangan teaches carrying basket weave c1960 AMHA B81.19.34

Anfesia Shapsnikoff was a fierce voice demanding that the true history of the “evacuation” of the Unangax be remembered for the forced removal it really was.

Renowned for her weaving of Aleut grass baskets, Anfesia flew to many communities throughout Alaska to teach children the lost art of Attu basket weaving.

The Twenty-First Legislature of the Alaska State Legislature recognized Anfesia on March 7, 2000, as an “Aleut Tradition Bearer” who “…served as nurse, church reader, teacher and community leader nearly all her life…Who contributed history and well being for all Alaskans.”

She served as a powerful role model within the Aleut communities where she taught and got involved in matters of importance to the people. “Anfesia’s influence in the Aleut community endures…. Her passion for Aleut culture has infused various Aleut organizations, and her willingness to serve on civic boards has inspired others to follow her example.”

Leanne Betasamosake Simpson is a Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg scholar, writer and artist, Her books are regularly used in courses across Canada and the U.S., including Dancing on Our Turtle’s Back, Islands of Decolonial Love, and The Gift Is in the Making. Her paper “Land As Pedagogy” was awarded the Most thought-provoking 2014 article in Native American and Indigenous Studies. Her latest book, As We Have Always Done: Indigenous Freedom Through Radical Resistance is due out soon from the University of Minnesota Press.

Caleen Sisk is the Spiritual Leader and Tribal Chief of the Winnemem Wintu Tribe, who practice their traditional culture and ceremonies in their territory along the McCloud River watershed in Northern California. Since assuming leadership responsibilities in 2000, Caleen has focused on maintaining the cultural and religious traditions of the Tribe as well as advocating for California salmon restoration, the Human Right to Water and the protection of indigenous sacred sites. She is also currently leading her Tribe’s efforts to work with Maori and federal fish biologists to return Chinook salmon to the McCloud River. For more than 30 years, Caleen was mentored and taught in traditional healing and Winnemem culture by her late great aunt, Florence Jones, who was the tribe’s spiritual leader for 68 years. Caleen’s traditional teachings and training comes from an unbroken line of leadership of the Winnemem Wintu Tribe.

Margo Tamez is an enrolled citizen of the Lipan Apache Band of Texas. Of Lipan Apache, Jumano Apache, and Spanish heritage, Tamez was born in Austin, Texas, and grew up in San Antonio. A teacher and activist, Tamez earned an MFA in creative writing from Arizona State University in 1997. Her collections of poetry include Alleys and Allies (1992), Naked Wanting (2003), and Raven Eye (2007).

She received a Poetry Fellowship from the Arizona Commission on the Arts, and both an Environmental Leadership Award and International Exchange Award from the Tucson Pima Arts Council. In 2004 Tamez and Joni Adamson organized the Symposium on Globalism and the Environmental Justice and Toxics Movement in Tucson AZ

-.-.-.-.-

Drinking under the Moon She Goes Laughing:

-.-.-.-.-

When the end was near

He threatened hands trembling

There is no end never his hands reaching to my face

You can’t leave taking off his shirt going for his pants

The trickle of sweat beading off his nose

-.-.-.-.-

Moon-orb spray metallic shimmer slicklove

Tripping numb night shadows

Crows perched on a streetlight

-.-.-.-.-

We’re terrestrial ants living in fragility

On Huhugam sacred ground

Jar of our dead

-.-.-.-.-

Like ragged cats my ghosts and I

Gossip in the alley behind a bar

My eyes grasp theirs a spark revolution

Feet without tracks on gravel

-.-.-.-.-

Our existence erased far off

From clinking beer bottles and vanity

-.-.-.-.-

On the bench outside a bookstore

We get erased see the news of the street

Resistance getting milled

-.-.-.-.-

My favorite ghosts and I bear down harder birth ourselves

-.-.-.-.-

On the bench outside a bookstore

Frigid wind wants to snatch our secrets

-.-.-.-.-

Hey nay ya na ya na ya na

I thank you thank you for your presence

My ghosts I thank you for your presence

Hey nay ya na ya na ya na ya na

This dilemma oh ancestors

O! ancestors !!!! I thank you thank you thank you

Hey nay ya na ya na ya na ya na

-.-.-.-.-

I’m still the Lipan Jumano land-grant mongrel

Nobody sees nobody recognizes an invisibility

Scudding through all the checkpoints

Border towns train tracks pesticide flybys welfare lines

-.-.-.-.-

Wings shifting shape

Scorpion’s venom injects me for the night

-.-.-.-.-

Green light spasms in the click click delete cut past

fucking do something do something different

-.-.-.-.-

An orgasm of light at the slippery edge

One good time to die

And live spreading like osmosis

-.-.-.-.-

Tripping grandmother rabbit on the moon

Always with that sorrowful look on her face

Make the medicine

Be artistic

Do what is necessary

-.-.-.-.-

Nicole Tanguay is a Cree two-spirit poet, playwright, musician, and advocate for Indigenous rights. Their poetry—which has been featured in anthologies such as Miscegenation Blues: Voices of Mixed Race Women and The Colour of Resistance: A Contemporary Collection of Writing by Aboriginal Women—explores topics like racism, environmental destruction, and violence against Indigenous peoples. Their poetry is raw and in your face, often tangling visceral descriptions of trauma, grief, and pain with the everyday survivance of Indigenous people. In “Blood,” for example, they memorialize Indigenous women who died “lying in the streets/ and in gutters of hell/ waiting for the great God to remember them/ for who they are/ children of this land.” They view poetry as a form of resistance and education on critical social justice issues.

Ulali is a Native American all-women a cappella group. Founded in 1987, it includes Pura Fé (Tuscarora/Taino), Soni (Mayan, Apache, Yaqui), and Jennifer Kreisberg (Tuscarora).

Ulali’s sound encompasses an array of indigenous music including Southeast United States choral singing (pre-blues and gospel) and pre-Columbian music.

Ar the 25th Annual American Indian Film Festival in San Francisco, CA in 2000, Ulali won the “Eagle Spirit Award” and each member of the group has won a “Native American Women’s Recognition Award” (NAWRE), presented by the Friends of Ganondagan in Rochester NY. Their video “Follow Your Hearts Desire” won “Best Music Video” at The American Indian Film Institute Awards.

Mahk jchi tahm buooi yahmpi gidi Mahk jchi taum buooi kan spewa ebi Mahmpi wah hoka yee monk Tahond tani kiyee tiyee Gee we-me eetiyee Nanka yaht yamoonieah wajitse

English Translation:

‘Our hearts are full

and our minds are good.

Our ancestors come

and give us strength.

Stand tall, sing, dance

and never forget who you are

or where you come from.’

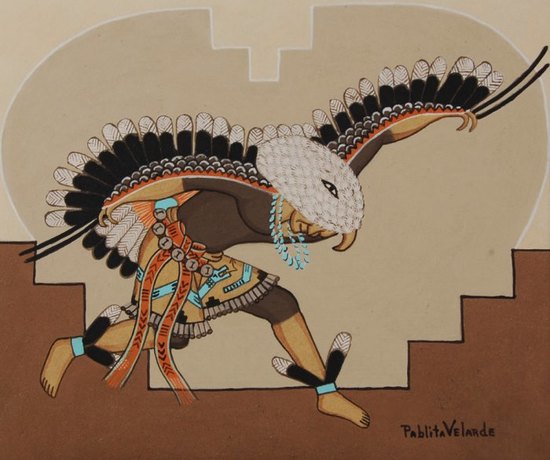

Pablita Velarde (1918 – 2006), Tse Tsan (Tewa, “Golden Dawn”) was born on the Santa Clara Pueblo near Española, New Mexico. Her mother died when she was 5 years old, and she and her sisters were sent to St Catherine’s Indian School in Santa Fe. At the age of fourteen, she was accepted to Dorothy Dunn’s Santa Fe Studio Art School at the Santa Fe Indian School. There, she becomes an accomplished painter in the Dunn style, known as “flat painting.”

In the beginning, she worked exclusively in watercolors, but later she began learning how to prepare her own paints from natural pigments ground from rocks and minerals.

Eagle Dancer

Eagle Dancer

Velarde was commissioned in 1939 by the National Parks Service under a WPA grant to depict scenes of traditional Pueblo life for visitors to the Bandelier National Monument, a site covering 50 square miles on the Pajarito Plateau in New Mexico which is the location of ancient pueblo structures dating between 1150 and 1600 AD.

In 1953, she was the first woman to receive the Grand Purchase Award at the Philbrook Museum of Art’s Annual Exhibition of Contemporary Indian Painting. In 1954 the French government honored her with the Palmes Académiques for excellence in art.

Her daughter, Helen Hardin, and her granddaughter Margarete Bagshaw became prominent artists in their own right.

Sarah Winnemucca Hopkins, Thocmentony “Shell Flower” (circa 1844 – 1891) was a Northern Paiute author, activist and educator.

Born near Humbolt Lake NV, into an influential Paiute family who were in favor of friendly relations with the arriving groups of Anglo-American settlers, she was sent to a Catholic school in Santa Clara CA. When the Paiute War erupted between the Pyramid Lake Paiute and the settlers, Sarah and some of her family made a temporary living in San Francisco and Virginia City on stage as “A Paiute Royal Family.” In 1865 while they were away, the US cavalry, attacked and killed 29 Paiutes, including Sarah’s mother and several members of her extended family.

Winnemucca became an advocate for Native American rights, traveling across the US to tell Anglo-Americans about the plight of her people. When the Paiute were interned in a concentration camp at Yakima, Washington, she traveled to Washington, DC to lobby Congress and the executive branch for their release. She also served US forces as a messenger, interpreter and guide, and as a teacher for Native American prisoners.

She published Life Among the Paiutes: Their Wrongs and Claims (1883), a book that is both a memoir and history of her people during their first forty years of contact with European Americans. It is considered the “first known autobiography written by a Native American woman.” Anthropologist Omer Stewart described it as “one of the first and one of the most enduring ethnohistorical books written by an American Indian,” frequently cited by scholars. Following the publication of the book, Winnemucca toured the US East, giving lectures about her people in New England, Pennsylvania, and Washington D.C. She returned to the West, founding a private school for Native American children in Lovelock, Nevada.

There has been some criticism of her family for pretending to be some kind of Paiute “Royalty” and for Winnemuca’s willingness to work for the American military, but she has also been honored for her activism, social work and education efforts.

Mary Youngblood (1958 – ) is a half-Aleut/half-Seminole composer and player of the Native American flute. She has been awarded three Native American Music Awards, the first female artist to win “Flutist of the Year,” in both 1999 and 2000, as well as winning “Best Female Artist” in 2000. She is also the first Native American woman to win a Grammy Award for “Best Native American Music Album”, and the first Native American woman to win two Grammy’s, for Beneath the Raven Moon in 2002 and Dance with the Wind in 2006.

In 2007 Mary Youngblood composed and played the flute music on the soundtrack for documentary film, “The Spirit of Sacajawea.”

Ms. Youngblood is on the advisory board of the World Flute Society.

x

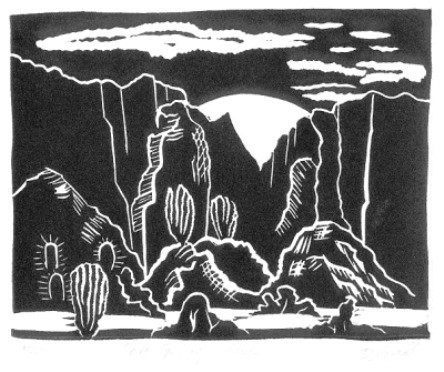

Ofelia Zepeda (1952 – ) is a member of the Tohono O’odham (formerly Papago) Nation, Ofelia Zepeda grew up in Stanfield, Arizona. She earned an MA and a PhD in linguistics from the University of Arizona and is the author of a grammar of the Tohono O’odham language, A Papago Grammar (1983). Zepeda’s poetry collections include Ocean Power: Poems from the Desert (1995) and Jewed’l-hoi/Earth Movements, O’Odham Poems (1996).

Deer Dancer

Deer Dancer

Zepeda was honored with a MacArthur Fellowship (1999) for her contributions as a poet, linguist, and cultural preservationist. She received a grant from the Endangered Language Fund for her work on the Tohono O’odham Dictionary Project. Zepeda has been a professor of linguistics and director of the American Indian Studies Program at the University of Arizona, as well as director of the American Indian Language Development Institute. She edits Sun Tracks, a book series devoted to publishing work by Native American artists and writers, at the University of Arizona Press.

-.-.-.-.-

Deer Dance Exhibition

-.-.-.-.-

Question: Can you tell us about what he is wearing?

Well, the hooves represent the deer’s hooves,

the red scarf represents the flowers from which he ate,

the shawl is for skin.

The cocoons make the sound of the deer walking on leaves and grass.

Listen.

Question: What is that he is beating on?

It’s a gourd drum. The drum represents the heartbeat of the deer.

Listen.

When the drum beats, it brings the deer to life.

We believe the water the drum sits in is holy. It is life.

Go ahead, touch it.

Bless yourself with it.

It is holy. You are safe now.

Question: How does the boy become a dancer?

He just knows. His mother said he had dreams when he was just a little boy.

You know how that happens. He just had it in him.

Then he started working with older men who taught him how to dance.

He has made many sacrifices for his dancing even for just a young boy.

The people concur, “Yes, you can see it in his face.”

Question: What do they do with the money we throw them?

Oh, they just split it among the singers and dancer.

They will probably take the boy to McDonald’s for a burger and fries.

The men will probably have a cold one.

It’s hot today, you know.

-.-.-.-.-

The saddest part of doing this project for me was the number of women I found who are “language keepers” — the last living fluent speakers of their people’s tongues. I can only hope that the current efforts being made to save these languages will be successful.

And felt such outrage and horror at the appalling mistreatment and genocide so many have endured, and which so many continue to face today. Every new day becomes part of our history as soon as it changes into yesterday. We can and must do better.

But I have also found great joy in this momentary meeting with such extraordinary women.

SOURCES

heard.org/… saintssistersandsluts.com/…

www.nmai.si.edu www.google.com/… Women Trailblazers of California: Pioneers to the Present, © 2012 by Gloria G. Harris and Hannah S. Cohen — The History Press

Leave a Reply