During the 1930s, with the United States in the midst of the First Great Depression, American Indian art began to emerge as a form of economic development as well as cultural expression. During this time there were a number of programs to educate Indian artists in both art techniques and in art marketing.

The Bureau of Indian Affairs lifted the ban on teaching traditional arts and music at its boarding schools in 1930. Lifting the ban was not based on any feeling that Indian cultures were to be encouraged, but upon the recognition that traditional Indian arts and crafts were a way for Indian people to make money.

In 1932, Mable Morrow established a program devoted strictly to Indian arts and crafts at the Santa Fe (New Mexico) Indian School. She brought in nine young Indian women from the Haskell Indian School to form the core of a two-year program that admitted only female high-school graduates. The new program intended to prepare Indian women for careers both as independent professional artists and as art teachers in federal Indian schools. A new building was constructed to house the arts and crafts program. Morrow developed a program which included silversmithing, pottery, weaving, beadwork, embroidery, basketry, carding, tanning, wool dying, and woodworking.

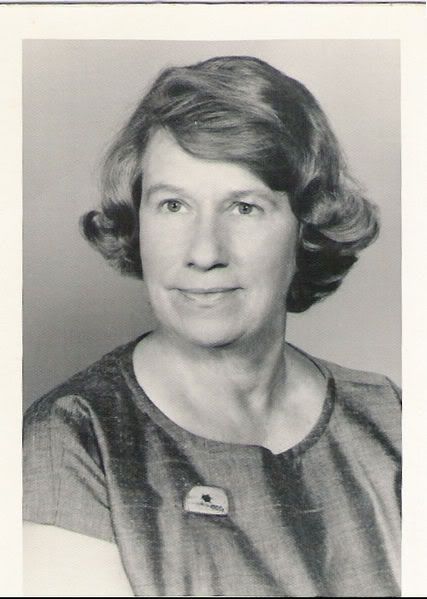

Dorothy Dunn, an art teacher who had recently graduated from the School of Art Institute of Chicago, opened an art studio at the Santa Fe Indian School in 1932. Dunn was not a stranger to either Indian students or Indian art. She had been the second grade teacher at the Santo Domingo Pueblo day school and she had taught at the San Juan Boarding School on the Navajo Reservation.

Dorothy Dunn is shown above.

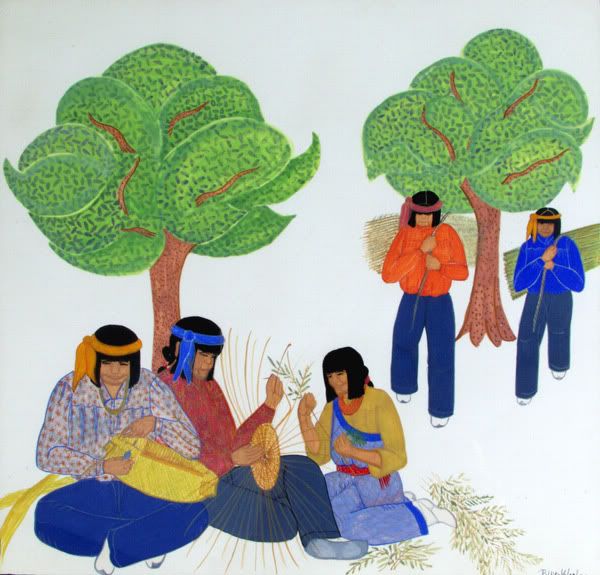

Under her tutelage, Indian students were encouraged to depict traditional ceremonial and tribal scenes, and plants and animals, using a flat, decorative, linear style. Her goals were to foster an appreciation of Indian painting and to produce new paintings with high standards. She felt that it was important to maintain tribal and individual distinctions in the paintings.

In class, the students sketched pictographic figures and had free-line brush practice. She discouraged borrowing motifs or styles from other tribal groups or from non-Indians. In order to provide her students with a broad art education, she borrowed books and historic objects from museums, took students on trips to the Laboratory of Anthropology and the Museum of New Mexico in Santa Fe. Dunn also brought in non-Indian lecturers to teach her students about their own heritage. She encouraged her students to exploit what she defined as Native tradition. In style and content the works produced by her students affirmed romanticized conceptions of the Indian. As a result, the Studio-style paintings found an eager market among non-Native patrons.

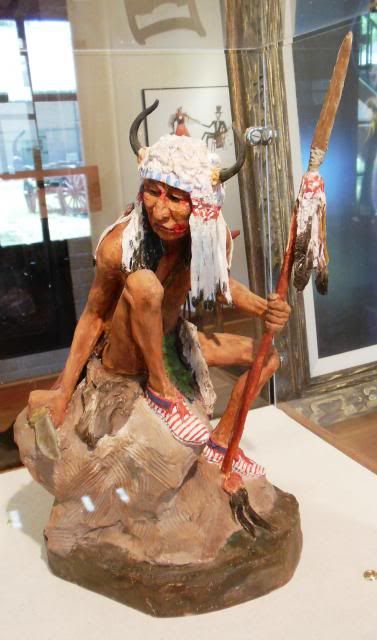

While Dorothy Dunn exposed her students to many different examples of art, her curriculum did not include any discussion of art theory or history, or of modern art movements. This experimental art program, later referred as The Studio, was instrumental in the education of many Indian artists, including Tewa artist Pablita Velarde and Chiricauha Apache artist Allan Houser.

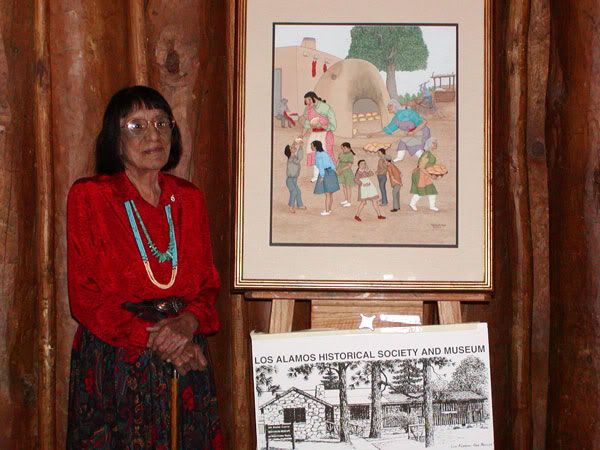

Pablita Velarde and her work are shown above.

A sculpture by Alan Houser is shown above.

In 1933, Dorothy Dunn began to teach her students to make earth color paintings to reproduce the colors traditionally used in painting pottery and ceremonial objects. This technique used pulverized dry organic pigments glued to a backing or wall in a fresco technique.

In 1932, Bacone College, a college for Indian students in Muskogee, Oklahoma opened its Art Lodge where students are exposed to Native American artistic traditions. Two years later, the college opened an art department under the direction of Creek artist Acee Blue Eagle.

Ataloa Lodge, the art museum at Bacone College is shown above.

At the urging of Indian Commissioner John Collier, Congress passed the Indian Arts and Crafts Act of 1935 which established a special board to promote the development of Indian arts and crafts. The purpose of the board was: (1) to enlarge the market for Indian art, (2) improve production, and (3) establish certification of Indian artists. With regard to the certification of Indian artists, Indian identity was seen as essential and following the racist conventions of the time, “Indian” was defined as someone who was of at least one-quarter Indian blood.

The act was intended to generate more income on reservations. The five member board worked to promote the development of Indian arts and crafts by teaching artists how to market their work and by educating the public about Indian-made products. The concept of Indian art, however, was not defined by the Indian artists, but by the collectors and tourists who wanted to possess objects that conformed to their own preconceptions about what constituted Native subject matter, style, or technique.

In 1937, anthropologist Alice Marriot started a program in Oklahoma to train Choctaw women in spinning. The project was an experiment by the Indian Arts and Crafts Board to increase Indian incomes through traditional native craft. Spinning was a deceptively simple craft. While learning the technical aspects of spinning required a short amount of time, its mastery takes years of practice. The Choctaw spinners were soon depressed to find that their work generated very little money.

In 1939, in an effort to promote Hopi silver as a unique art form, Mary-Russell Ferrell Colton from the Museum of Northern Arizona sent a letter to 18 Hopi silversmiths in which she wrote:

“The tourist does not know the difference between the genuine hand made and the machine made and so they are often misled, but they would like to have some guarantee, that the silver which they buy is really hand made.”

She included paperwork from the Indians Arts and Crafts Board with instructions on how to get their mark. She also wrote:

“Hopi silver should be entirely different from all other Indian silver, it should be Hopi silver, using only Hopi designs.”

In 1939, the Papago Tribal Council in Arizona encouraged basketmaking by establishing a revolving fund to buy baskets and then to sell them through the Papago Arts and Crafts Board.

Leave a Reply