In 1890 American fear, xenophobia, and religious intolerance led to the massacre of Sioux Indians at Wounded Knee in South Dakota. While there have been many books written about this massacre, there were a number of related incidents prior to this.

Setting the Stage for Violence in 1890:

In South Dakota, the Great Sioux Reservation was broken up into five smaller reservations occupying about half the land as previously. The other half of the reservation was opened up for non-Indian settlement at bargain prices. The proceeds from the sale of the former reservation lands were supposed to go to the Indians as compensation for their lost territory. The railroads were given permission to survey and build lines with no regard for any Sioux concerns.

At that same time, in Nebraska, the Christian Indian newspaper The Word Carrier reported about the Paiute prophet Wovoka:

“The Indians are generally excited over a so-called super-human visitor who is making frequent visits to the Indians in the Rocky Mountains. He performs some sleight of hand work and has made them believe that he is the Christ the Son of God. He is nothing but a petty representation of the Mormons of Utah.”

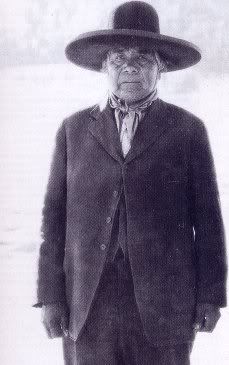

Paiute prophet Wovoka is shown above.

Missionary Mary Collins reported that Sitting Bull was a Ghost Dance leader. She recommended that he be banished:

“A few years in a prison learning English and a good trade would have a quieting influence upon the old man and his followers.”

While Sitting Bull, like other Indian leaders, was aware of Wovoka as a Paiute prophet in Nevada, he had no contact with him and was not involved with the new religion.

An editorial in the Black Hills Daily Times in response to rumors about the Ghost Dance:

“The Indians must be killed as fast as they make an appearance and before they can do any damage. It is better to kill an innocent Indian occasionally than to take chances on goodness.”

In Nebraska, the Christian Dakota language newspaper Iapi Oaye reported on the Ghost Dance movement with preaching and teaching. Calling Wovoka a false prophet, it quoted Bible verses showing that the religion was wrong.

In South Dakota, Kicking Bear introduced to the Lakota a special shirt. The shirts were decorated with a star and crescent moon and feathers at the shoulders. According to non-Indian sources, he claimed that bullets would not go through these shirts. The new shirts became a part of the Ghost Dance movement among the Sioux.

Kicking Bear’s Ghost Dance shirts seem to have been inspired by the shirts worn by the Arapaho Ghost Dancers. These shirts are made out of white muslin with a painted line of blue and one of yellow on the back. The Arapaho shirts, in turn, seem to have been inspired by the Mormon endowment robes of white muslin ornamented with symbols of their faith.

Anti-Indian Violence in 1890:

In Nebraska, the non-Indian residents of Chadron, concerned about rumors regarding an Indian upr55ising stemming from the Ghost Dance religion, passed a resolution asking for government troops. The resolution states in part:

“Resolved, that the leaders and instigators of criminality in savages should receive at the hands of the Government the punishment the law provides for traitors, anarchists and assassins.”

In South Dakota, Anglo settlers fearing an uprising from the Lakota Ghost Dancers asked the government for rifles and ammunition. Two militia units were organized to kill Indians. South Dakota’s governor told them “Be discreet in killing the Indians.”

At the Cole Ranch, Dead Arm was shot and killed as he rode into the trading post. His body was scalped and allowed to lay in the dirt for three days while cowboys poked sticks at it and photographers took pictures of it.

Near the Lakota Stronghold, the militia ambushed and killed about 75 Ghost Dancers, including women and children. One of the militiamen took seven pack loads of items from the dead — guns, war bonnets, ghost shirts — and used them to start a museum in Chicago.

The United States 8th Cavalry sent out a unit on a reconnaissance mission near the Lakota Stronghold. The unit came across a small band of Lakota and killed them all. The Indians’ guns were removed and the bodies buried. The troops were sworn to secrecy.

In South Dakota, James McLaughlin, the Indian agent for the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation, angrily confronted Sioux leader Sitting Bull, telling him that Wovoka’s messiah doctrine was absurd and that Sitting Bull should stop his people from dancing. Sitting Bull replied that he and McLaughlin should go to Nevada and meet with Wovoka to find out first hand about the new religious movement. Sitting Bull promised McLaughlin that he would not hesitate to enlighten his people if Wovoka’s words were false and he would urge them to give up the ritual. McLaughlin refused the challenge. McLaughlin claimed that Sitting Bull was uncooperative, and he threatened the dignified leader with jail.

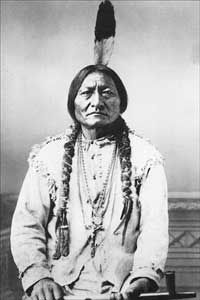

Sitting Bull is shown above.

Indian police were sent to arrest Lakota leader Sitting Bull because of rumors that he intended to attend the Ghost Dance at Pine Ridge. In a short fight, Sitting Bull and several of his followers were killed by the Indian Police. The Indian agent’s reasons for arresting Sitting Bull:

“Sitting Bull is a polygamist, libertine, habitual liar, active obstructionist, a great obstacle in the civilization of those people, and he is so totally devoid of any of the nobler traits of character, and so wedded to the old Indian ways and superstitions that it is very doubtful if any change for the better will ever come to him.”

The Aberdeen Saturday Pioneer, in its report on the death of Sitting Bull:

“The Whites, by law of conquest, by justice of civilization, are masters of the American continent, and the best safety of the frontier settlements will be secured by the total annihilation of the few remaining Indians.”

The newspaper was published by L. Frank Baum who later gained fame for his book The Wizard of Oz.

Aftermath:

Commenting on the spread of the Ghost Dance on the Sioux reservations which led to the massacre at Wounded Know, Lakota writer and physician Charles Eastman would write in 1918:

“The teachings of the Christian missionaries had prepared them to believe in a Messiah, and the prescribed ceremonial was much more in accord with their traditions than the conventional worship of the churches.”

Leave a Reply