During the nineteenth and part of the twentieth century, American policies regarding Indians focused on assimilation. Under these policies, the American government sought to destroy Indian cultures: their religions, their languages, their manner of dress, their government, their traditional economies, their traditional families, and anything that might be considered Indian. Individual Indians were to assimilate into American mainstream society. One of the primary mechanisms of assimilation was the boarding school.

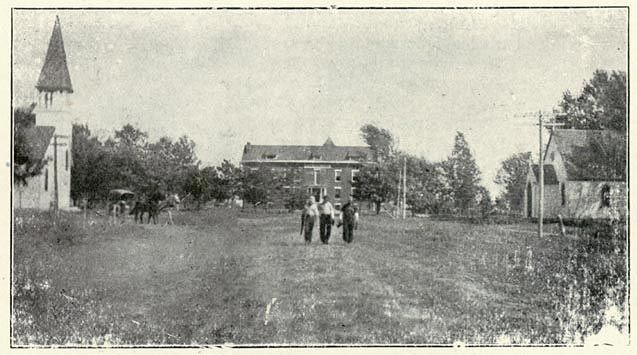

Inspired by the glowing success stories coming from the Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania, the Indian Office (which would later become the Bureau of Indian Affairs) in 1879 decided that a boarding school should be established in Oregon to provide middle and high school education for the Indian nations along the Pacific Coast. In an off-reservation location, far removed from parental and tribal influences, the Indian Office felt that educators would be able to inculcate their students with the primary tenets of American society: patriotism, Christianity, the English language, and husbandry.

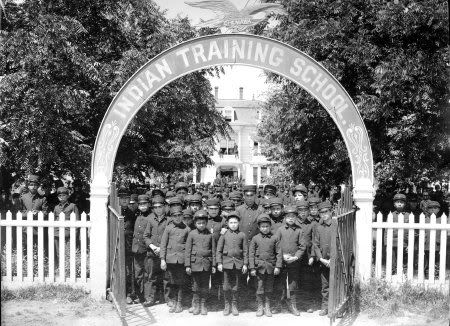

Initially, the location selected for the new school was Forest Grove in a site adjacent to Pacific University. It was originally named the Normal and Industrial Training School, but it would later become the Forest Grove Indian Training School, the Salem Indian Industrial School, the Harrison Institute, and finally, the Chemawa Indian Boarding School. Hereafter the school will be referred to simply as Chemawa.

The photograph above is from the Oregon State Library.

Classes at the new school began with 18 students (14 boys and 4 girls), all from the Puyallup Reservation. School superintendent Edwin Chalcraft writes:

“Chemawa was essentially a vocational school, where attention was about equally divided in training both the hand and the mind, the object being to prepare students to go forth after graduation and take their place with other citizens of our Country.”

In 1880, President Rutherford B. Hayes visited Chemawa to see for himself how the government was educating Indian children. In a speech to the crowd who had come to see him, the President told them that some people in the United States had come to the conclusion that God had decreed that Indians should die off like wild animals. He went on to say:

“If they are to become extinct, we ought to leave that to Providence, and we, as good patriotic, Christian people, should do our best to improve their physical, mental, and moral condition.”

He also reminded people that the Indians had once owned America and that the Americans displaced them. He concluded by saying:

“I am glad that Oregon has taken a step in the right direction. I am glad that she is preparing Indian boys and girls to become good, law-abiding citizens.”

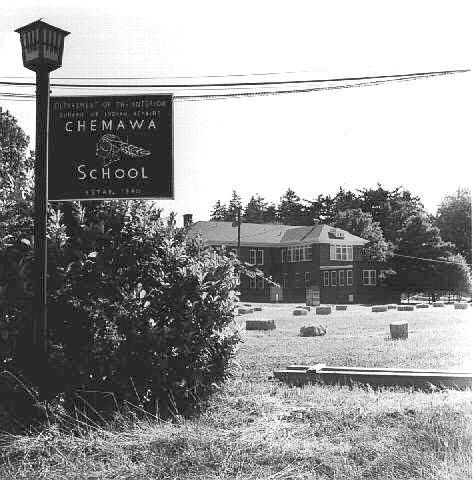

In 1885, fire destroyed the original school and the facility was moved to its present location just north of Salem, Oregon.

With regard to the role of Indian boarding schools, One Indian agent wrote in 1887:

“Education cuts the cord which binds them to a pagan life, places the Bible in their hands, and substitutes the true God for the false one, Christianity in place of idolatry, civilization in place of superstition, morality in place of vice, cleanliness in place of filth, industry in place of idleness, self-respect in place of servility, and, in a word, an elevated humanity in place of abject degradation.”

In 1897, Chemawa obtained a foot-power printing press and began publication of a school newspaper called the Chemawa American. School superintendent Edwin Chalcraft reports:

“The Chemawa American, issued weekly in magazine form, seven by ten inches in size, contained sixteen to twenty-four pages of reading matter, and four to six pages of advertising by Salem merchants.”

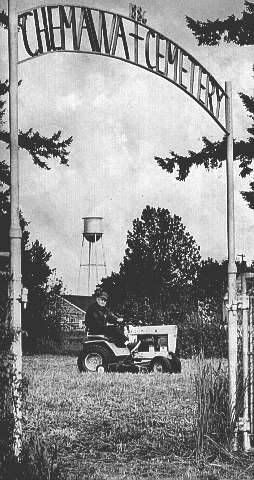

The basic concept of the American Indian boarding schools, pioneered by Carlisle and Chemawa, was that the students, under the guise of industrial education would actually underwrite a good portion of their education through their free labor. By 1921, federal funding for boarding schools was $204 per student. This compares with $360 per boy at state reform schools and $436 per girl at state schools for girls. In order for the boarding schools to operate at these costs, students were required to work for their room and board.

In 1934, federal Indian policy changed: no longer was the primary focus on assimilation, but instead the tribes were allowed more self-government. With regard to education, it was now more possible to teach Indian cultures in the boarding schools. In 1939, Chemawa began the Reservation Survey Course. This survey course was designed to teach the students about their own reservations and the surrounding areas. It was felt that this would help them to select a more useful vocational course that would offer the best chance at employment on their reservations. Homerooms were established by tribal affiliation and each had a council modeled on the tribal council. It was hoped that students would become familiar with their reservation environment and would eventually take their place in the reservation community. The course was inspired by the 1934 Indian Reorganization Act.

At the end of World War II, Indian policies once again began to change: there was pressure to return to assimilation. In 1945, Chemawa began to require a course in Ethics and Christian Doctrine for all grades:

“All students are required to attend and for this reason the ministers have been asked not to stress a particular creed but to present moral and christian [sic] doctrine such that it will be accepted by any student regardless of his chosen faith.”

When the Bureau of Indian Affairs found out about the class the school was informed that it was illegal to require a religion class.

In 1950, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs ordered classes in BIA schools to stop stressing Native culture and to prepare Indian students for off-reservation employment. This included the reinstitution of the old efforts to curb the use of Native languages

In 1956, the regular academic program at Chemawa was terminated and the focus shifted to the Navajo Special Education Program. The Navajo are a southwestern tribe, far away from Oregon. Only 150 non-Navajo students remained at the school and these were to be transferred to public schools or to other boarding schools.

By 1967 there were sufficient educational facilities on the Navajo reservation so the Bureau of Indian Affairs began phasing out the Navajo students at Chemawa. Once again education at Chemawa emphasized an academic high school program. The vocational program was reduced to a pre-vocational program that included cooking, office practice, welding, auto shop, and small engine repair.

In 1976, the Affiliated Northwest Tribes met at Chemawa and unanimously agreed that the school was

“essential for an Alternative Educational Resource for the forty-two Northwest reservations and urban areas.”

By 1977, Chemawa’s mission was to provide for the enrichment and future prosperity of all Native American peoples. In the words of one staff member:

“Its prime function is to produce and prepare Native American peoples capable of performing adequately, if not superiorly, within a world society that is economically and financially dominant without having to degrade, denounce or substitute their culture heritage or uniqueness.”

Today, Chemawa remains as one of two Indian boarding schools in the United States. It is the oldest continuously operated boarding school in the United States.

Leave a Reply