The 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo between the United States and Mexico gave the United States what is now the southwest. Under the Discovery Doctrine-a legal concept under which Christian nations are given the right, and perhaps the obligation, to govern all non-Christian nations-the Yavapai became a domestic dependent nation within the American empire. The Yavapai, living in their homeland in an area which would later become known as Arizona, did not know that they had become a part of the United States.

First, about terminology: the name Yavapai may be derived from En-ya-va-pai-aa which means “people of the sun,” or from Yawepe which means “crooked mouth people.”

Second, the Yavapai are not Apache, although many nineteenth-century Americans and a few twentieth-century historians considered them to be an Apache group. Linguistically they are classified as Upland or Northern Yuman and thus most closely related to the Walapai (Hualapai) and Havasupai.

Politically, the Yavapai were not a single political entity, but were a loose association of locally organized groups speaking mutually intelligible but nevertheless distinct subdialects. The Yavapai were divided into three groups: Yavepe (also spelled Yavapé; Northeastern Yavapai), Tolkapaya (also spelled Tolkepaya; the Western Yavapai), and Kewevkapaya (also spelled Kwevkepaya; the Southeastern Yavapai). In addition, there may have been a fourth group: the Wipukepa.

Yavapai oral tradition tells that the people first emerged from the underground through a large hole called Ahagaskiaywa. Today this hole is identified as Montezuma’s Well. After some time, water flooded from the hole and destroyed all of the people except for a single woman who found refuge in a hollow log.

Traditional Yavapai territory stretched from the San Francisco Peaks in the north, to the Pinal Mountains in the east, and to the confluence of the Gila and Colorado Rivers in the southwest. Some archaeologists feel that the Patayan culture which developed along the Colorado River about 1,300 years ago was ancestral to the Yavapai. These scholars suggest that about 700 years ago, some Patayan groups began leaving the Colorado River area and moving east into the highlands of Arizona. These groups then evolved into the Yavapai.

Hunting was an important source of food for the Yavapai. The primary big game animals hunted by the Yavapai were mule deer, pronghorn antelope, elk, and desert bighorn sheep. Deer were driven into blinds by a number of men hunting together. In addition, the deer were stalked by hunters who were camouflaged with deer-headed masks. They also hunted rabbits, squirrels, skunks, porcupines, raccoons, bobcats, mountain lions, wild turkeys, quail, desert tortoises, and lizards.

The Yavapai followed an annual round based on the ripening of wild plant foods in different zones. They would travel from one area to another, timing their arrival so that the wild foods would be ready for harvest. Yavapai families exploited a great variety of wild foods.

Following their annual round, the Yavapai women would begin harvesting squawberries and other green plants at lower elevations in May. They would then gather mesquite beans and various cactus fruits (including saguaros). Next, they would begin harvesting ironwood and palo verde seedpods which would be ground into meal. As these plants went out of season in midsummer, the Yavapai would move into the higher elevations where they would exploit resources such as walnuts and manzanita berries. By early fall, they would be gathering acorns, juniper berries, and prickly pear fruits. As the weather cooled in October, they would turn to gathering piñon nuts and assorted berries.

One of the wild foods that was important to the Yavapai and to the other Yuman-speaking tribes in the region was agave, a succulent which was usually gathered in the Spring. Agave, also known as the century plant, was the most dependable source of carbohydrates for many tribes. The Yavapai roasted the agave in pits lined with heated stones. It would usually take a day to prepare the agave to be roasted and then roasting would take another day and a half. Women would pound and dry the roasted agave flesh, producing fibrous slabs that were easily transported or cached and lasted for years. For the Yavapai, agave was often their staple food.

The Yavapai supplemented their hunting and gathering with agriculture. For them, agriculture was unpredictable, difficult, and hard work. The Yavapai planted corn, beans, squash, and tobacco in washes, streams, and near springs. In some areas, they would also plant watermelons, pumpkins, and sunflowers. Following planting, the band would leave to engage in gathering and hunting, returning to the fields intermittently and finally for harvest. They would return in late summer and early fall to harvest whatever had matured and had not been eaten by animals.

The Yavapai would sometimes water their fields with small irrigation ditches. The banks of dependable, slow-moving streams like the Verde River provided the best planting areas. These were also ideal for weirs and diversion ditches.

The Yavapai were active traders and often went on trading expeditions to the west coast, south into Mexico, and north into Paiute country. They also traded with the Hopi and Zuni. At the villages on the Hopi mesas, the Yavapai would barter for corn, fruit, and blankets. Navajo traders would often bring these same goods to Yavapai camps.

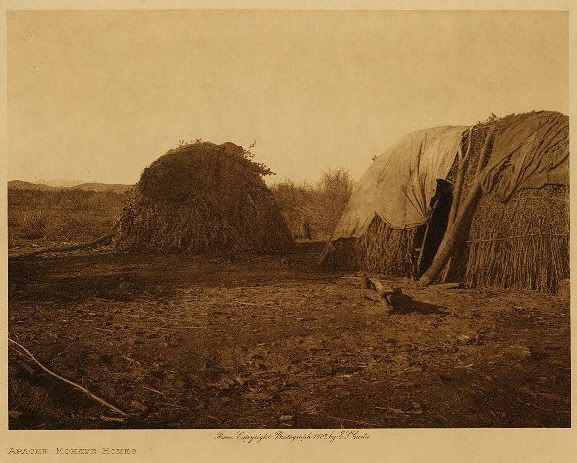

The primary form of housing for the Yavapai was the domed hut called a uwa. This structure, oval in shape covering an area about 10 feet by 20 feet, was framed with ocotillo (cactus) branches or other wood, then covered with layers of grass, bark, dirt, and animal skins. In the summer, the uwas were built without walls to allow the cooling breeze to flow through, while in the winter they were closed huts. The Yavapai often temporarily camped in caves and rockshelters that could easily be heated by fire.

Among the Yavapai basketry was an important craft. They made burden baskets, parching trays (flat baskets for winnowing and parching seeds), water bottles (smeared with pitch to make them water proof), and containers for boiling food. In boiling food, the baskets were filled with water which was brought to a boil by adding hot rocks. The baskets were made with coiling and twining techniques.

A Yavapai basket is shown above.

In general, the Yavapai lived in small bands of extended families which were identified with certain geographic regions in which they resided. Government among the Yavapai tended to be informal. There were no tribal chiefs. Certain men became leaders because others chose to follow them, heeded their advice, and supported their decisions. Men who were noted for their skills as warriors were called mastava (not afraid) or bamulva (person who goes forward). Other warriors were willing to follow such men into combat. Some Yavapai men were noted for their wisdom and speaking ability. Called bakwauu (person who talks), they would settle disputes within the camp and advise others on the selection of campsites, work ethics, and food production.

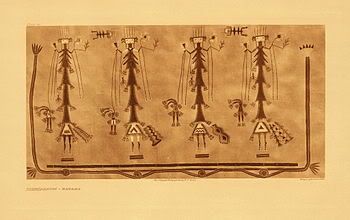

For the Yavapai, disease and illness were caused by evil spirits. The medicine people-called basemachas-would counteract the evil spirits by singing, dancing, smudging with different herbs, and with the use of gourd rattles. Using a variety of dry colors-red clay, charcoal, yellow pollen, and others-the basemachas would create spiritual pictures in the sand. Following this, the ceremonial participants would rub the powders from the picture on the bodies.

Among the southwestern Yavapai there is a group curing ceremony in which masked dancers impersonate spirits called Akoka. The dancers are summoned into a brush enclosure by a shaman swinging a noise maker. The patients are treated by the masked dancers by having pollen placed on different parts of their bodies.

Leave a Reply