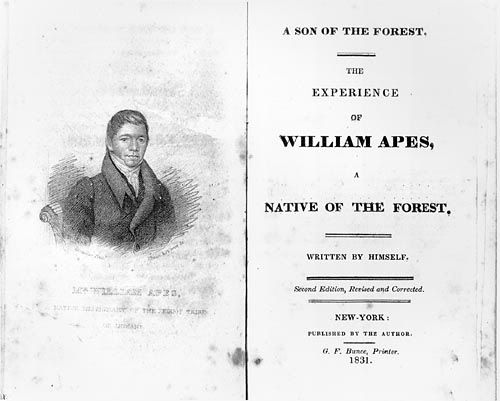

In 1829, Andrew Jackson became President of the United States. Jackson felt that since the Constitution prohibited the establishment of a new state within the boundaries of another without the agreement of the later and since the states had not agreed to the establishment of a Cherokee nation, the establishment of a Cherokee nation was unconstitutional. Thus, Indians had only two choices: to submit to the states or to remove themselves. Jackson pretended that the Indian nations in the Southeast were hunters and gatherers and therefore had made no improvements to the land which would entitle them to claim the land. Partially in response to Jackson and to the false view of Indians that many non-Indians held, a Pequot Christian minister, William Apess, published his Son of the Forest. The autobiography tells of a life of abuse and oppression. Using the Christian-based style of the time, he tells his story as a spiritual confession and in so doing is able to comment on the anti-Indian prejudices held by non-Indians. This book was one of the earliest books written by an American Indian.

William Apess was born in 1798 to William and Candace Apes. He would later add the additional “s” to his name for undisclosed reasons. In his autobiography, he claimed to be the grandson of a granddaughter of King Philip.

During his youth Apess was indentured to a number of Euro-American families during which time he acquired some basic education. He eventually ran away and joined a militia in New York. He saw service in the War of 1812 and by the age of 16 he had become an alcoholic.

In the 1820s, William Apess became convinced that he was being called to preach the Gospel and in 1829 he was ordained as a Methodist minister. As a Methodist minister, Apess became an iterant preacher, traveling throughout New England. His congregations included Native Americans, African Americans, and Euroamericans. In 1831, he wrote and published The Increase of the Kingdom of Christ, a Sermon. This enhanced his reputation as a minister and public speaker.

In 1833, William Appes wrote The Experiences of Five Christian Indians of the Pequot Tribe in which he described the conversion experiences of a number of Pequot. While the stories of the conversion experience were something which interested non-Indians, the stories actually emphasize the theme of learned self-hatred. The stories illustrate how the mythology of colonial history had actually prevented Indians from developing positive individual and group identities.

Among those described in the book is Sally George, one of the principal leaders of the Mashantuck Pequot. Another Pequot woman described in the book is Hannah Caleb who had developed a rather cynical attitude toward Christianity. She observed:

“They openly professed to love one another, as Christians, and every people of all nations whom God hath made-and yet they would backbite each other, and quarrel with one another, and would not so much as eat and drink together, nor worship God together.”

His work as itinerate minister brought him into contact with the Mashpee, a Christian Indian community in Massachusetts. In 1833, the Mashpee unsuccessfully attempted to evict the English minister who was appointed to them, to regain their meeting house, and to prevent outsiders from exploiting their wood and hay. In their petition, signed by 102 people, to the governor and council of Massachusetts, the Mashpee stated:

“That we as a tribe will rule our selves, and have the right so to do for all men are born free and Equal says the Constitution of the Country.”

When the government did not respond favorably to their petition, the relations between Indians and non-Indians in the area grew tense. Many of the Indians were openly armed. The Indians stopped some non-Indians from taking wood from tribal land and consequently the authorities arrested William Apess who had been counseling them.

William Apess convinced the governor that full-fledged armed revolt was possible and the Mashpee won most of their demands. Mashpee was to be incorporated as an Indian district. As an Indian district, the Indians would be able to elect their own selectmen, who, in turn, would be responsible for the management of all tribal property. The selectmen would also be empowered to make any laws necessary to carry out their duties.

While William Apess had been formally adopted into the Mashpee community, he was still considered an outsider and therefore had no authority to speak for the tribe.

In his 1833 essay An Indian’s Looking Glass for the White Man, Apess asked:

“Can you charge the Indians with robbing a nation almost of their whole continent, and murdering their women and children, and then depriving them the remainder of their lawful rights, that nature and God require them to have?”

In 1835, Apess wrote about the Mashpee “uprising” in his book Indian Nullification of the Unconstitutional Laws of Massachusetts Relative to the Mashpee Tribe, or the Unpretended Riot Explained. In this book criticized the proposals for Indian removal which were being advocated by Andrew Jackson and others. He accused Christians of committing the crime of slavery against Indian people:

“How they could go to work to enslave a free people, and call it religion, is beyond the power of my imagination, and outstrips the revelation of God’s word.”

In 1836, William Apess delivered a public lecture entitled Eulogy on King Philip at the Odeon in Boston. The presentation was prepared in honor of the 160th anniversary of the death of Philip who led the Pequot in what is known as King Philip’s War. While non-Indians in New England often demonized Philip, Apess described him in positive terms. In his lecture, Apess quoted a speech given by Philip to the other Indian leaders about the English colonists:

“Brothers, these people from the unknown world will cut down our groves, spoil our hunting and planting grounds, and drive us and our children from the graves of our fathers and our council fires, and enslave our women and children.”

In his eulogy, the war against the Pequot was presented as an unwarranted attack on peaceful Indians-an account that contradicted Puritan histories. He contrasted the Native American restraint and their goal of self-preservation with the Puritans’ savagery and brutality, specifically quartering and refusing to bury murdered Indians and selling captive Indians into slavery in Bermuda.

In 1839, William Apess died as a result of alcoholism at the age of 41.

Leave a Reply