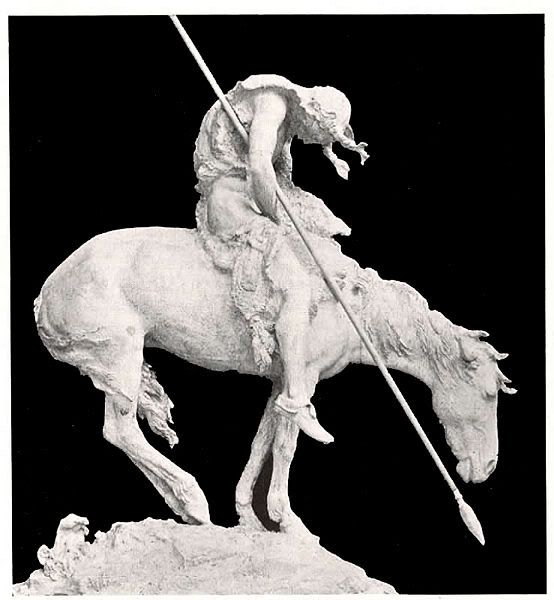

During the nineteenth century non-Indian scholars, intellectuals, government officials, and others were convinced that American Indians were a dying race and that by the twentieth century, Indians would have vanished. Thus, when the twentieth century started Indians became invisible, relics of a mythical past. The symbol of American Indians was “The End of the Trail,” a 1915 equestrian statue by James E. Fraser which was shown at the San Francisco Exposition. Small replicas of the statue were widely distributed and displayed in many middle class homes as the symbol that American Indian destiny had run its course.

During the era from the beginning of the twentieth century to the Second World War, the image of American Indians was firmly set in a mythical past created in the vivid imaginations of popular books, magazines, and movies. This image had little to do with historical reality and formed in the minds of most Americans an unreal sense of American Indian history. During this time, however, a number of writers, both Indian and non-Indian, began an attempt to create a more realistic, and perhaps more accurate, image of American Indian history.

Non-Indian Writers:

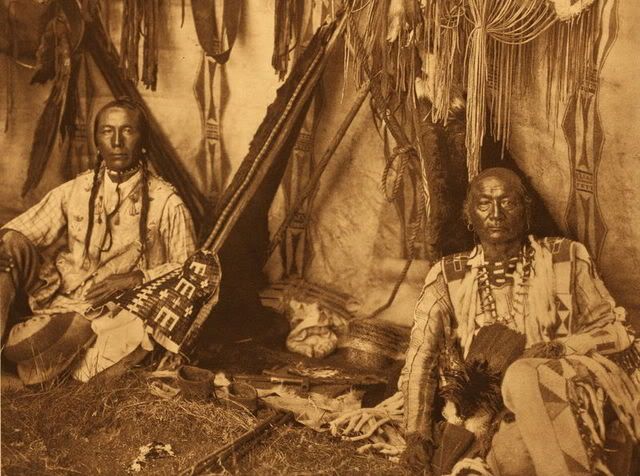

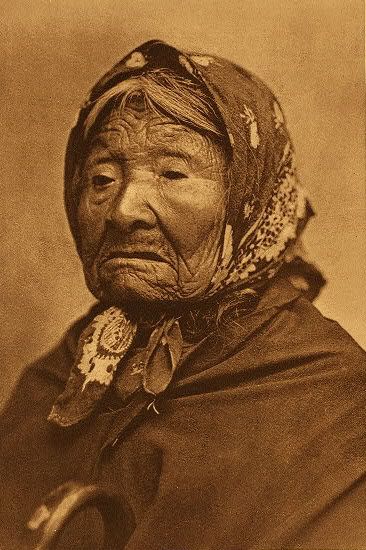

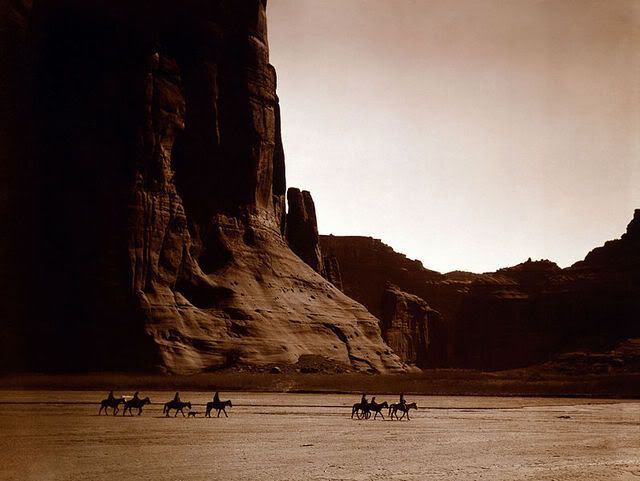

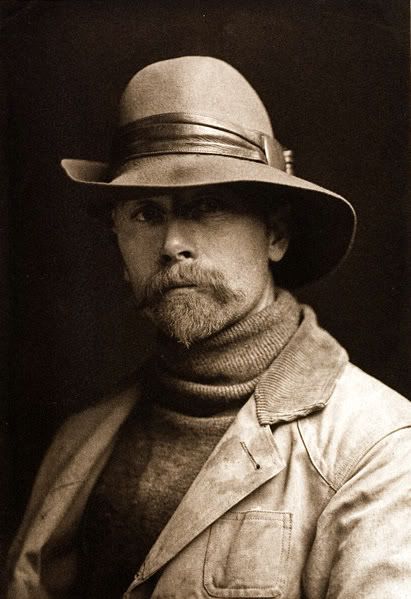

Perhaps the best known, and certainly most massive publishing project prior to the Second World War was photographer Edward S. Curtis’s 30-year project documenting 80 tribes in 40,000 pictures. The material, which included both photographs and ethnological text, was published in a 20 volume set. In his photographs, Curtis sought to capture his vision of the vanishing Indian and thus often supplied his subjects with wigs (long hair for Indian men was not allowed at this time) and props, including shirts, headdresses, tipis, and canoes. Curtis chose to ignore contemporary living conditions in order to create images of a mythical past.

A Curtis photograph of a Blackfoot (Piegan) lodge is shown above. Curtis removed the alarm clock which was between the two men.

One of Curtis’ Indian portraits is shown above.

A Curtis photograph from Navajo country is shown above.

Edward S. Curtis, Self Portrait, is shown above.

In 1936, historian Angie Debo finished the initial draft of her book And Still the Waters Run which documented the criminal conspiracy to cheat the Indians out of their land in Oklahoma. Concerned about the political and legal ramifications of the book, the editor for the University of Oklahoma Press sent it to Commissioner of Indian Affairs John Collier. Collier turned the manuscript over to Flathead writer D’Arcy McNickle. McNickle commented that-

“nothing quite so ambitious has been attempted. Indian history has been so neglected by serious students and so overrun by sentimentalists and free-lance commentators of various stripes and colors that it is a real joy to come across a work of such competence.”

In 1937, concerned about the potential for libel in Angie Debo’s And Still the Waters Run, the University of Oklahoma Press submitted it to a University law professor who told them that it would be impossible to avoid libel suits. The President of the University recommended that the book not be published. Debo’s contract for publishing the book was therefore cancelled. The book was finally published in 1940 by the Princeton University Press. Following the publication of the book, she was barred from teaching in Oklahoma.

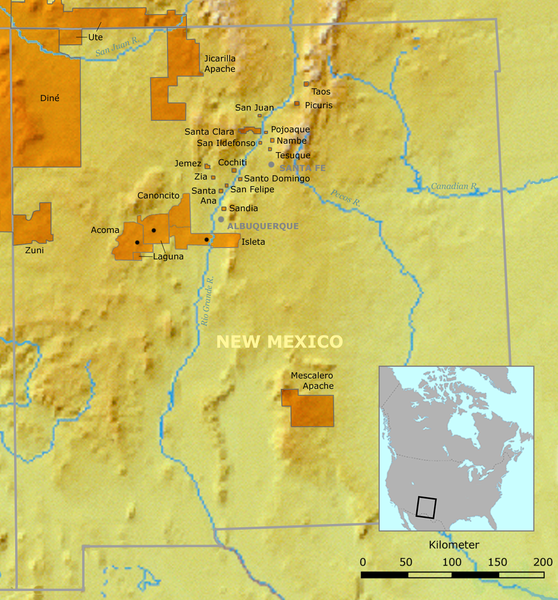

One of the reasons for publishing books about Indians during this time was to promote tourism. In 1903, the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway published Indians of the Southwest as a guide to the cultures of the region specifically designed for train passengers. The text was written by George Dorsey of the Field Museum in Chicago and told tourists how to explore the region. The book also provided information for those tourists who were content to do their adventuring from the train.

In order to promote tourism to Glacier National Park in Montana, the Great Northern Railroad published American Indian Portraits in 1928. This colorful book featured paintings of Blackfoot Indians from the reservation adjacent to the Park.

Some of the books written during this era were political and focused on federal Indian policies. In a 1910 book entitled The Indian and his Problem former Commissioner of Indian Affairs Francis Leupp condemned treaties and was firm in the conviction that Indians must be individualized and assimilated. The Red Man in the United States, written in 1919 by G. E. E. Lindquist for the Inter-Church Movement, documented poverty on Indian reservations. The book was written in an old-style missionary language and praised those Indians who walked the “Jesus Road.” The book had minimal impact on federal Indian policy.

George Bird Grinnell’s The Fighting Cheyennes was published in 1915. At this time there were a number of stories being published about army battles with the Indians. While the non-Indian public showed a great deal of interest in these stories, Grinnell took a very different approach and collected the Indian stories about the battles.

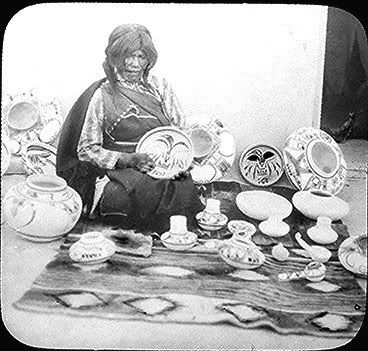

Anthropologist Ruth Bunzel published The Pueblo Potter in 1929. In this book she identified Nampeyo (Tewa from the village of Hano on the Hopi reservation) and María Martínez (from San Ildefonso Pueblo) as two potters who had originated new directions and new styles in Native American pottery. No longer were Pueblo potters faceless artisans: Bunzel, by giving Nampeyo and Maria credit for personal preference and imagination within the Pueblo pottery tradition, showed them to be modern individuals.

Nampeyo is shown above.

As Told To Books:

Indian voices have often been interpreted for non-Indian audiences by non-Indian writers in the format of “as told to” books. The most famous of these is Black Elk Speaks in which former Lakota holy man Black Elk shared his sacred teachings with John G. Neihardt, the Nebraska poet laureate. The book was largely ignored when first published in 1932, but later became a popular source of sacred information for both Indians and non-Indians.

Black Elk was treating a sick boy in 1904 when a Catholic priest burst into the room, disrupted the ceremony, threw away Black Elk’s drum and rattle, and called him Satan. Black Elk felt that the priest’s powers were greater than his and vowed to never again practice the Lakota religion. He took instruction in Catholicism and was baptized Nicholas Black Elk. He never again practiced the Lakota spiritual ceremonies. He became a Catholic catechist and converted many Indian people to Christianity.

Black Elk Speaks organizes Lakota religion in a Christian framework and thus communicated with people who were raised in Christianity. There are many who feel that the book is more about Christianity than the aboriginal religion.

Other “as told to” books include Goodbird the Indian: His Story, written in 1914 by anthropologist Gilbert L. Wilson based on information provided by Wolf-Chief, an Hidatsa man. The book is intended to teach Christian children about other cultures. In 1932 the story of Crow medicine woman Pretty Shield was told by Frank Linderman in the book Red Mother (later published as Pretty-Shield: Medicine Woman of the Crows). In her story, she talked about the traditional ways of the Crow in Montana.

Indian Writers:

In 1911, a group of six Indian intellectuals-Arthur Caswell Parker (Seneca), Dr. Charles A. Eastman (Sioux), Sherman Coolidge (Arapaho), Thomas L. Sloan (Omaha), Charles Daganett (Peoria), Dr. Carlos Montezuma (Yavapai), and Zitkala-sa (Sioux)-founded the Society of American Indians. The new organization hoped to forge a new relationship between the dominant non-Indian society and American Indians. Several of these founders wrote books about various aspects of Indian history and culture.

Dr. Charles Eastman, a physician, wrote ten books beginning in 1902 with Indian Boyhood. His The Soul of the Indian was published in 1911. He wrote:

“I have attempted to paint the religious life of the typical American Indian as it was before he knew the white man. I have long wished to do this, because I cannot find that it has ever been seriously, adequately, and sincerely done. The religion of the Indian is the last thing about him that the man of another race will ever understand.”

Eastman, who was a Christian, wrote of the missionaries:

“The first missionaries, good men imbued with the narrowness of their age, branded us as pagans and devil-worshippers, and demanded of us that we abjure our false gods before bowing the knee at their sacred altar.”

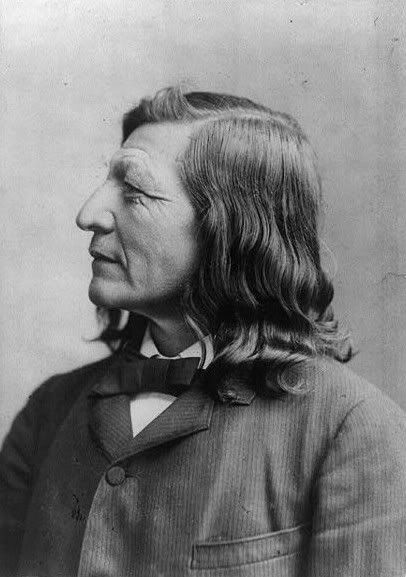

Eastman is shown above.

The Indian Today was published in 1915. In it Eastman wrote:

“It is the aim of this book to set forth the present status and outlook of the North American Indians.”

In a chapter entitled “The Indian in College and the Professions,” he wrote about Carlos Montezuma, a Yavapai physician whose practice was in Chicago:

“He stands uncompromisingly for the total abolition of the reservation systems and the Indian Bureau, holding that the red man must be allowed to work out his own salvation.”

Eastman’s book Indian Heroes and Great Chieftains was published in 1918 and presented the stories of 15 Indian leaders. Eastman explained the purpose of the book:

“I should like to present some of the greatest chiefs of modern times in the light of the native character and ideals, believing that the American people will gladly do them tardy justice.”

He also explained the concept of the “chief”:

“It is a singular fact that many of the ‘chiefs’, well known as such to the American public, were not chiefs at all according to the accepted usages of their tribesmen. Their prominence was simply the result of an abnormal situation, in which representatives of the United States Government made use of them for a definite purpose.”

Seneca anthropologist Arthur Caswell Parker published The Constitution of the Five Nations in 1916. The book included a series of documents describing Deganawida and Hiawatha and the founding of the Iroquois Confederacy. Parker argues that the Iroquois governmental system is “the greatest ever devised by barbaric man on any continent.”

Arthur Caswell Parker is shown above.

Arthur Caswell Parker’s The Indian How Book was published in 1927. The book was an attempt to explain to non-Indians how Indians did things. In the book, he combined factual information about Indians with practical advice about surviving outdoors. The book countered some common racial stereotypes and the common notion that all Indians were nomadic hunters. Parker wrote about the Iroquois Three Sisters-corn, beans, squash-and pointed out that the Iroquois had large fields at the time of their first contact with the French.

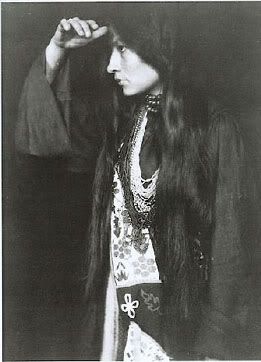

Yankton Sioux writer Zitkala-Sa’s collection of American Indian Stories was published in 1921. Her essay “Why I Am a Pagan” was retitled as “The Great Spirit” and was edited to remove some material. With these changes, the tone of the essay changed from anger to reassuring peace.

Zitkala-Sa is shown above.

Oxford educated Osage historian John Joseph Mathews published Wah’Kon-Tah: The Osage and the White Man’s Road in 1931. This became the first book by a Native American writer to be selected by the Book-of-the-Month Club.

Luther Standing Bear, a Lakota who had graduated from Carlisle Indian School and had been a part of Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West Show, wrote a number of books, including My People the Sioux, My Indian Boyhood (1931), The Land of the Spotted Eagle (1933) and Stories of the Sioux (1934).

Luther Standing Bear is shown above.

The Middle Five: Indian Schoolboys of the Omaha Tribe, written by Francis LaFlesche in 1900, presented a nostalgic portrait of a student’s experiences at the Presbyterian mission school on the Omaha Reservation.

Lucy Thompson (Che-na-wah Weitch-ah-wah), a Klamath/Yurok from California, self-published To the American Indian in 1916. In this book she argued that she was in a better position than any other person to tell the true facts of the religion of her people.

The Autobiography of a Winnebago Indian was published in 1913. In this autobiography Sam Blowsnake (also known as Crashing Thunder) told about his life and his conversion to the Native American Church (peyote religion). The book was originally transcribed in a syllabary adapted for use with the Winnebago language and then translated into English by Oliver La Mere.

In 1921, Maxidiwiac, an Hidatsa woman, published Wa-Hee-Nee: An Indian Girl’s Story, Told by Herself.

Federal Writers’ Project:

The Federal Writers’ Project (FWP) began in 1936 as an art project for the Works Progress Administration (WPA). With regard to Indians, the writers were advised to consult the Bureau of American Ethnography reports and with reservation officials to determine tribal histories. If the Indians interviewed by the writers gave different versions of this history, these were to be included in the guide. Indians, however, were seen as a group that existed outside of history as the histories were to begin with the Europeans and Indian history treated separately.

Leave a Reply