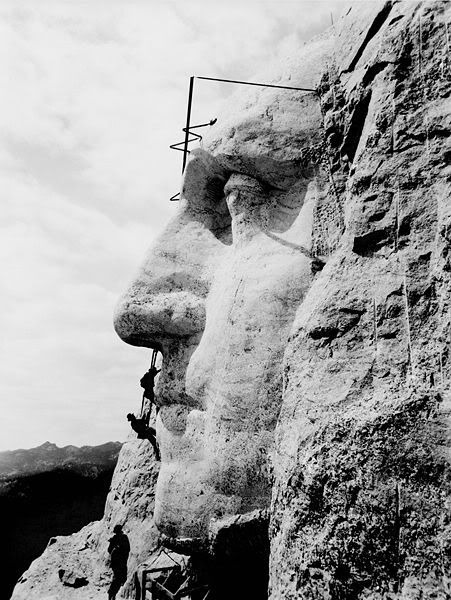

The Black Hills in South Dakota is an area which is sacred to several tribes, including the Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho. Geologically, the Black Hills are the site of an ancient upheaval that pushed the rocky strata far above the surrounding plains. The resulting peaks trapped the clouds and gave the region its own climate. During the summers, this was an area which was often used for ceremonies-sweat lodges, vision quests, and Sun Dances-and for gathering medicinal plants.

In 1851, the United States, in the Treaty of Fort Laramie, assigned the Black Hills to the Sioux in spite of claims to this area by the Cheyenne and Arapaho. By 1875, there were at least 1,200 American miners in the area in direct violation of the treaty. Instead of following the law and protecting Indian rights, the United States ordered the Sioux to stay away from the region and then engaged in a military campaign against them in an attempt to acquire title to the area. In 1877, the Sioux were forced to relinquish their rights to the Black Hills. The new agreement ignored the provision in the 1868 treaty which required three-fourths of adult Sioux males to sign any land cession agreement. Instead, the chiefs and two head men from each tribe signed. At this time, neither Congress nor the American public was in a mood to be bound by legal technicalities.

By the first part of the twentieth century, the Sioux began a new battle, this time in the American courts, to regain the Black Hills. In 1910, a Sioux delegation from the Standing Rock Reservation in South Dakota travelled to Washington, D.C. where they met with attorney Z. Lewis Dalby to discuss the Black Hills situation. Dalby studied the matter and concluded that a successful claim would be doubtful. In spite of this negative report, the following year the Black Hills Treaty Council was organized on the Cheyenne River Sioux Reservation to prepare a suit in the U.S. Court of Claims.

In 1913, Sioux historian Bad Heart Bull (also known as Amos Bad Heart Buffalo and Amos Bad Heart Bull) died at the age of 74. In 1890 he had begun a project of recording tribal history based on what the elders had taught him. The history was done in a pictorial (Winter Count) format and consisted of more than 400 pictures. Among the pictures is a map of the Black Hills which emphasizes its sacred sites.

Fighting to regain the Black Hills in the American legal system costs money. In 1914, the Sioux began to stage “singings” at reservation dance halls as a way of raising money to pay for legal representation and related costs in their fight to regain the Black Hills. The agents on the reservation opposed this fight and therefore responded by prohibiting the “singings.” In addition, the Indian Bureau refused to release any tribal money for pursuing their claim.

In 1917, a traditional Lakota chief, encouraged by the Lakota physician Charles Eastman, requested a council to discuss the Black Hills claim. The superintendent of the Rosebud Reservation recommended that the council be denied as the young men in such a council would not be likely to oppose the opinions of the elders. Consequently the Commissioner of Indian Affairs denied permission for the council.

Finally, in 1920, the Sioux were able to file a claim in the Court of Claims regarding the taking of the Black Hills in South Dakota.

In 1930, a Sioux delegation from the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota, including Iron White Man, George Little Wound, Emil Afraid of Hawk, and Henry Standing Bear, travelled to Washington, D.C. where they met with the Commission of Indian Affairs to discuss their Black Hills Claim.

More than a decade after the case had been filed, the Court of Claims heard oral arguments on the Sioux claim for the Black Hills in 1941. There appears to be no record of this hearing and it is unclear as to whether or not any Sioux tribal leaders were actually present. In 1942, the Court of Claims rejected the Sioux claims for the Black Hills. Legal historians describe Judge Benjamin Littleton’s decision as a “masterpiece of judicial obfuscation.”

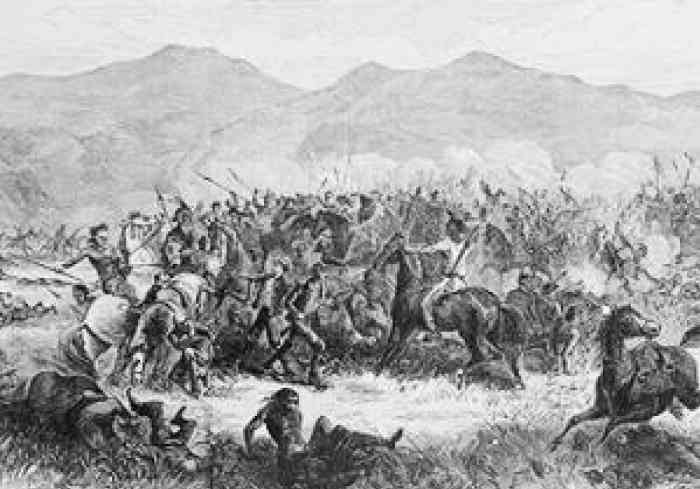

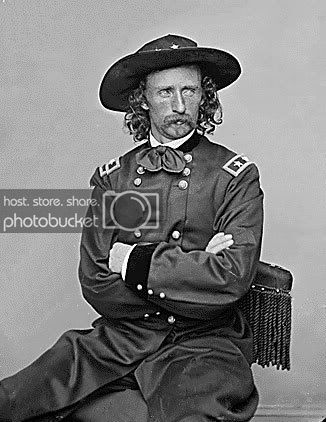

As the courts are rejecting the Sioux claims, the misinformation which was being fed to the general public increases. In 1942, Hollywood presented another picture of the Sioux in They Died With Their Boots On, a story of Lt. Col. George Custer’s defeat in the 1876 Battle of the Greasy Grass (Little Bighorn). Not only is Custer elevated to the rank of General, but he is also portrayed as the noble friend of the Indians, a man dedicated to protecting the Black Hills for the Sioux. Crazy Horse, on the other hand, appears to be inarticulate, immature, and perhaps somewhat insane.

In 1943, the Supreme Court refused to review the Court of Claims decision regarding the Sioux claim for the Black Hills. At this point it looked as if the Sioux battle for justice in the American legal system had been defeated.

Leave a Reply