During the nineteenth century, expositions and world fairs were seen as a profitable way for communities to promote themselves while educating the masses. Since Indians were seen as a vanishing people at this time, Indians were often an important attraction at these events. The 1898 Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition held at Omaha, Nebraska, was no exception. The goal of the Exposition was to showcase the development of the West, from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Coast. Indians were, of course, a part of this story, though usually seen as hindrances to development.

An aerial view of the exposition is shown above.

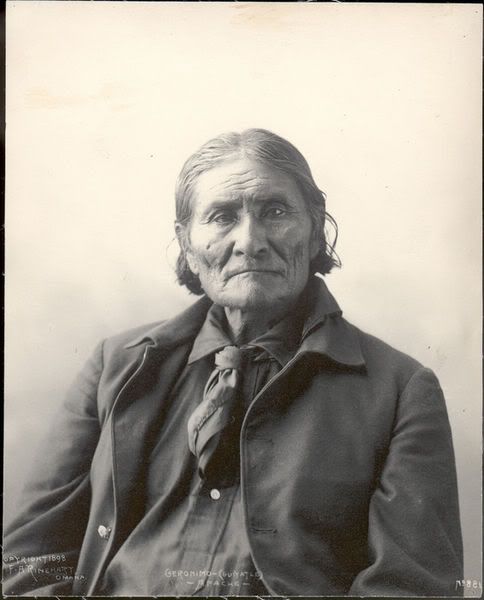

One of the participants in the Exposition was the Apache leader Geronimo. Following this exhibition, he became a frequent visitor to fairs, exhibitions, and other public functions. Since he was a well-known Indian leader and warrior, Geronimo was a great drawing card. At the Exposition and the many events which followed, he made money by selling pictures of himself, bows and arrows, buttons off his shirt, and even his hat.

Portraits of Geronimo taken at the Exposition are shown above.

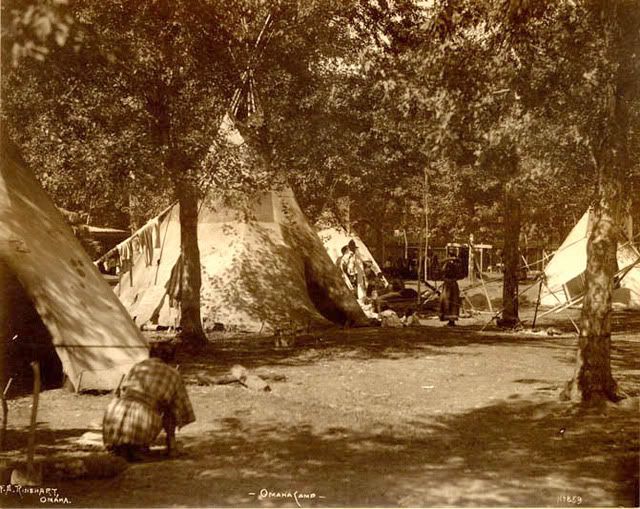

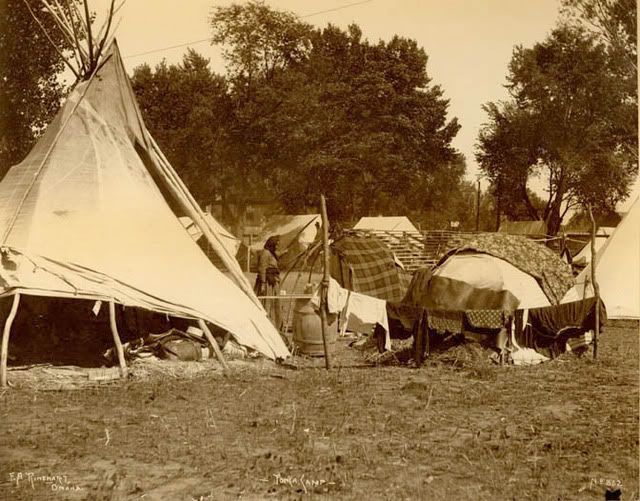

An important part of the 1898 Exposition was the Indian Congress. According to the promoters, the Indian Congress allowed a social and cultural exchange among the participating tribes. The Congress was actually a large encampment in which numerous tribes had set up their lodges. Visitors were encouraged to wander through the encampment and see how Indians lived. A total of 545 Indians were selected from 35 tribes for the encampment: preference was given to “full-bloods” and those who had traditional outfits.

The Omaha camp is shown above.

The Ponca camp is shown above.

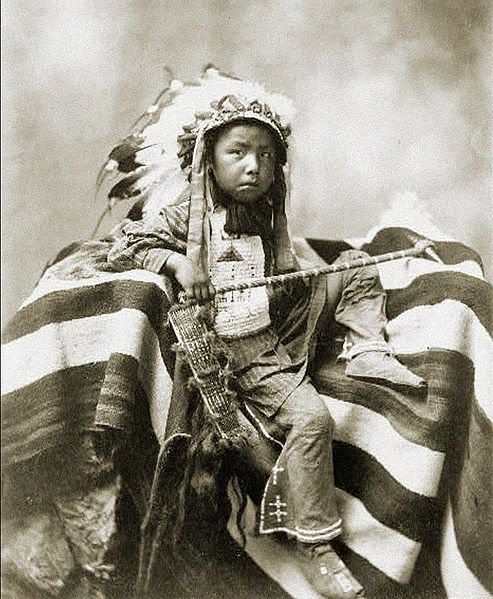

Government officials realized that the general public had little interest in educated Indians: the public wanted to see “wild” Indians with elements from traditional life including tipis, foot races, games, and so on. The participants in the Indian Congress, therefore, put on ceremonials, war dances, and sham battles for the general public. The sham battles were put on at the urging of a non-Indian fraternal group known as the Improved Order of Red Men. The sham battles were, of course, always won by the dominant non-Indians (or, presumably, the more civilized Indian tribe). This underscored the message that Indians were a race in decline whose only choices were to submit to American rule or to become extinct.

A young Sioux boy at the Exposition is shown above.

While most of the Indians were from Plains tribes which utilized the tipi, the Indian Congress did include Indians from other areas and other forms of Indian architecture were exhibited. The Wichita, for example, constructed a grass house.

From the Southwest, a delegation of 20 men from Santa Clara pueblo attended. The tourists had an interest in Pueblo pottery, but since there were only men in the delegation, they could not demonstrate traditional Pueblo crafts such as pottery-making. In the Pueblo tradition, the women are potters.

Among the notable Indian leaders at the Indian Congress was the seventy-year-old White-Man, a Kiowa Apache hereditary chief.

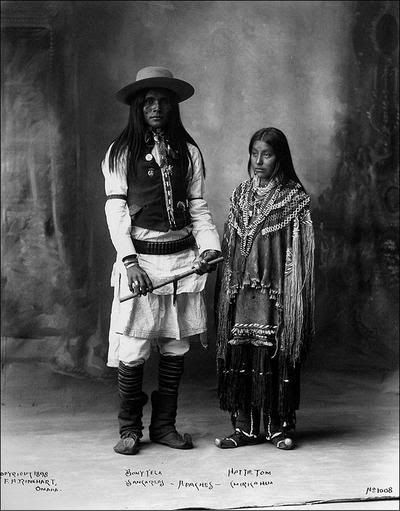

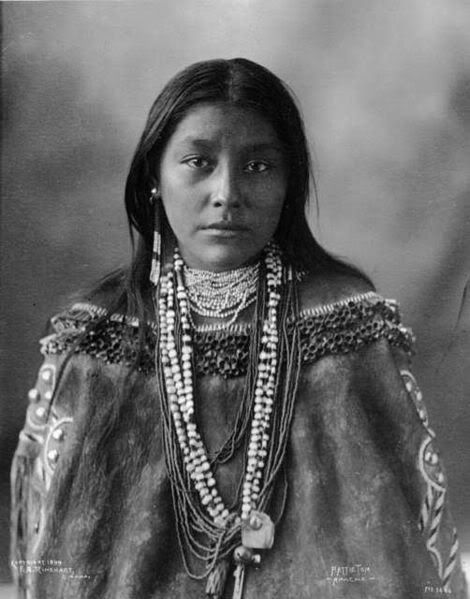

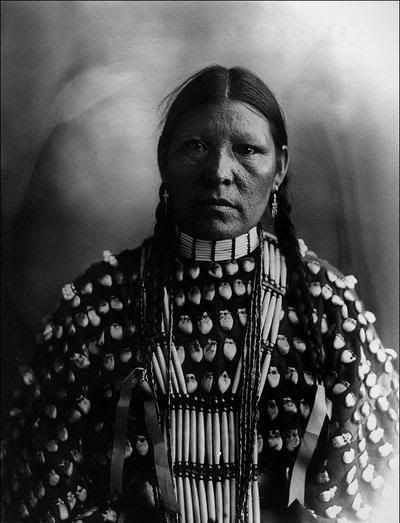

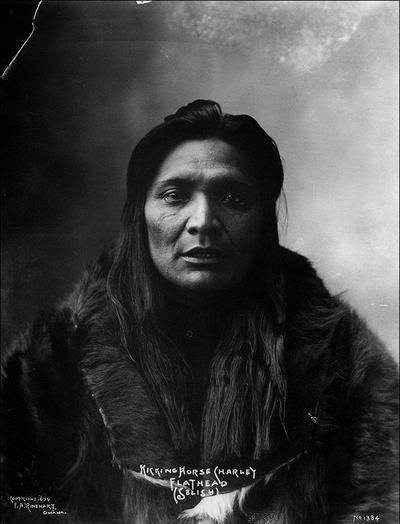

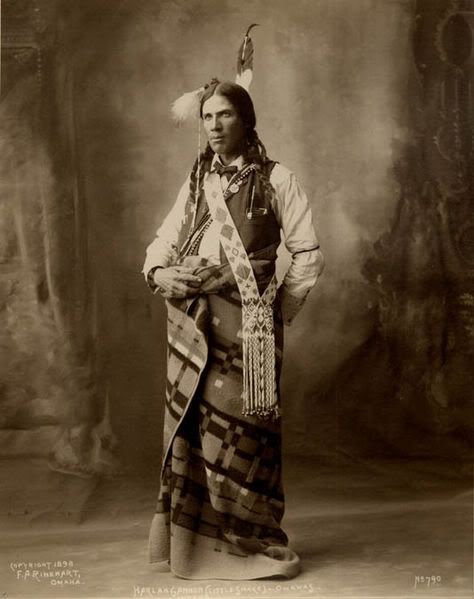

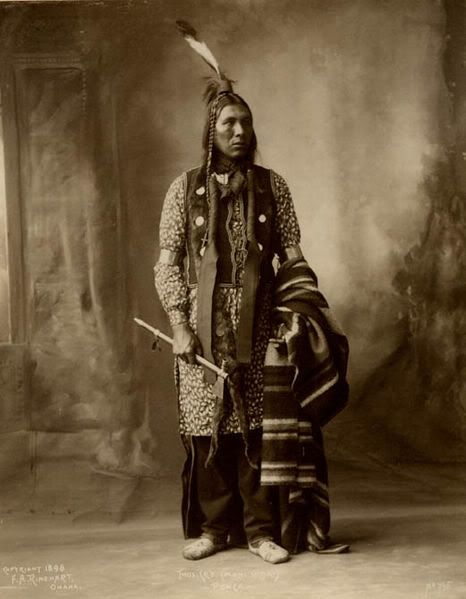

Many of the Indians who attended were photographed in a studio setting. Some of these are shown below.

Apaches are shown above.

Hattie Tom, Chiricahua Apache, is shown above.

Freckle Face, Arapaho, is shown above.

Kicking Horse, Flathead Salish, is shown above.

Little Snake, Omaha, is shown above.

Moni Chaki, Ponca, is shown above.

Sarah Whistler, Sauk and Fox, is shown above.

Touch the Clouds, Sioux, is shown above.

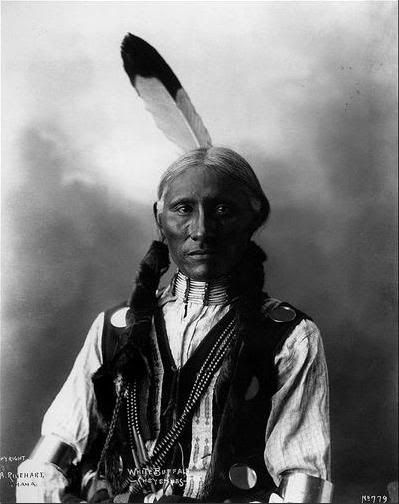

White Buffalo, Cheyenne, is shown above.

Leave a Reply