The Great Basin Culture Area includes the high desert regions between the Sierra Nevada and the Rocky Mountains. It is bounded on the north by the Columbia Plateau and on the south by the Colorado Plateau. It includes southern Oregon and Idaho, a small portion of southwestern Montana, western Wyoming, eastern California, all of Nevada and Utah, a portion of northern Arizona, and most of western Colorado. This is an area which is characterized by low rainfall and extremes of temperature. The valleys in the area are 3,000 to 6,000 feet in altitude and are separated by mountain ranges running north and south that are 8,000 to 12,000 feet in elevation. The rivers in this region do not flow into the ocean, but simply disappear into the sand.

The Great Basin is an ecologically sparse environment punctuated by small areas where water, game, and plant life are abundant. Summers can be fiercely hot and the winters bitterly cold. The land is unfavorable for farming and contains little game for food. This is an area which seems inhospitable to human habitation, yet Indian people have lived here for thousands of years. This was the last part of the United States to be explored and settled by the European-Americans.

Aboriginal life in the Great Basin required a rather intimate knowledge of a fairly large territory-often several hundred square miles-which encompassed the full range of desert biomes or ecologic communities. In other words, the Indian tribes which called the Great Basin home had to have a great deal of environmental knowledge in order to survive.

Linguistically all of the Indian people of the Great Basin, with the exception of the Washo, spoke languages which belong to the Numic division of the Uto-Aztecan language family. The Numic languages appear to have divided into three sub-branches-Western, Central, and Southern-about 2,000 years ago. About a thousand years ago, the Numic-speaking people expanded northward and eastward. The linguistic and archaeological data seem to suggest that the Numic-speaking people spread into the Great Basin from southeastern California.

Great Basin families were primarily nuclear families: that is, they were composed of a man and a woman and their children. At times, there might be other people who were also a part of the household, such as a younger brother, a grandfather, a widowed aunt. Beyond the nuclear family, people were linked by blood relationships, marriage relationships, adoptions, and friendships. These various and extensive linkages gave the nuclear family access to many different resource areas, something that was very important during times of food resource shortage in the home area.

One of the characteristics of the Great Basin cultures is sexual egalitarianism. Both boys and girls were free to engage in sexual exploration that could lead to a trial marriage. There was instruction in abortion methods as well as contraception. Divorce was simply a matter of either partner returning to their parental camp.

Among some of the Indian tribes of the Great Basin, such as the Northern Paiute and the Shoshone, a woman would sometimes marry a set of brothers – a practice called fraternal polyandry by anthropologists. This appears to be a response to sparse, scattered populations and the difficulty in finding eligible mates. There were also some instances of polyandry involving two cousins as well as unrelated males. While polyandry usually involved two males, there were a few instances of polyandry with three males.

With the harsh nature of the environment, Indian bands tended to be small – rarely larger than 30 people in the desert areas and up to 100 in other areas – and they usually used places near water sources for their residential sites. Band membership tended to be fluid. While many of the band members were related to each other by blood or by marriage, people were free to leave one band and join another. Band leadership was not autocratic and members were free to pursue an independent course when they so desired.

The tribes of the Great Basin Culture Area include Shoshone, Bannock, Gosiute, Paiute, and Ute.

Shoshone:

The Shoshone are often divided into four general groups: (1) the Western Shoshone who lived in central Nevada, northeastern Nevada, and Utah, (2) Northern Shoshone who lived in southern Idaho and adopted the horse culture after 1800, (3) Eastern Shoshone of Wyoming who adopted many of the traits of Plains Indian culture, and (4) Southern Shoshone who live in the Death Valley area on the extreme southern edge of the Great Basin.

The Northern Shoshone groups include the Fort Hall Shoshone, the Lemhi Shoshone, the Mountain Shoshone, the Bruneau Shoshone, and the Boise Shoshone. The Lemhi Shoshone hunted buffalo in western Montana, but depended primarily upon salmon for their subsistence. The Bruneau Shoshone were not a horse people and depended largely on salmon and camas. The Boise Shoshone also used salmon and camas as primary foods and also hunted buffalo in Wyoming and Montana.

Shoshone bands, like other groups in the Great Basin and Plateau Culture Areas, were often named after their dominant food source. Thus mountain-dwelling Shoshone were known as Tukudika (“eaters of bighorn sheep” or sheep eaters). Other Shoshone groups include the Agaidika (salmon eaters), Padehiyadeka (elk eaters), Yahandeka (groundhog eaters), Pengwideka (fish eaters), Kamuduka (rabbit eaters), Tubaduka (pine-nut eaters), and Hukandeka (seed eaters), and the Kukundika (also spelled Kutsundeka: buffalo eaters).

The Shoshone (also spelled Shoshoni) take their name from the Shoshone word sosoni’ which refers to a type of high-growing grass. Some of the Plains tribes referred to the Shoshone as “Grass House People” referring to the conically-shaped houses made from the native grasses. They also were referred to as the “Snakes” or “Snake People” by some Plains groups. This term comes from the sign which the people used for themselves in hand sign languages. While the hand motion made to represent “Shoshone” seemed to represent a snake to some signers, among the Shoshoni it referred to the salmon. Among the Plains Indians who often referred to the Shoshone as Snakes, the salmon was an unknown fish. The Shoshone often refer to themselves as newe.

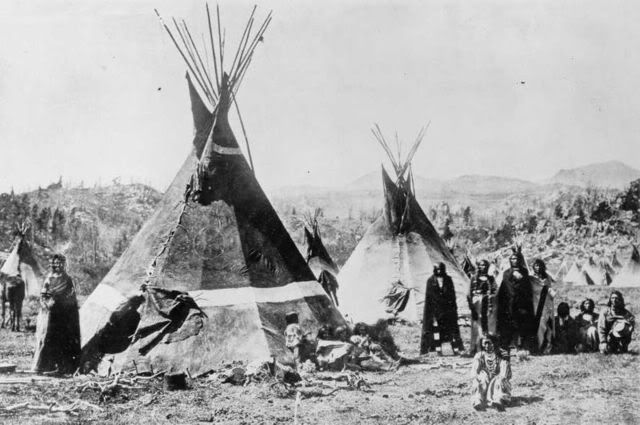

A nineteenth century Shoshone camp is shown above.

The Sheepeater Shoshone were known for making compound bows from the horns of mountain sheep, buffalo, and elk. In making a bow from the horns of a mountain sheep, the horns would first be heated to make them pliable and then straightened. The horn would be heated and shaped until there was a tapered piece from each of the ram’s two horns about 18 to 24 inches in length. The butt ends of the horns would then be carefully beveled and joined by laying a separate piece of horn over the joint. This joint would then be tightly wrapped with wet rawhide. To further strengthen the bow, strips of animal sinew would be glued to the back. In the Yellowstone National Park area, the bow makers would throw the horns into a hot spring and leave them there until they became pliable.

A carefully made horn bow would take about two months to complete. Such a bow could send an arrow completely through a bison. The Sheepeater Shoshone horn bows were prized by other tribes and in trading they were valued as being worth a horse and a gun. A typical Sheepeater bow had a pull strength of sixty-five pounds. This meant that the archers had to have considerable upper body strength.

Reservation-era Shoshone moccasins are shown above.

The leader of a Shoshone band-often dubbed “chief” by non-Indians-was often given the title of “talker” (daigwahni’ in Shoshone). The primary duty of the talker was to keep informed about the ripening of plant foods in different localities and to impart his information to other band members. The person designated as talker was usually a gifted speaker who used only the power of persuasion during group decisions.

Bannock:

The Bannock, who call themselves Bana’kwut (“Water People”), were called Buffalo Eaters and Honey Eaters by other tribes. According to Brigham Madsen, the Bannock “migrated from the desert areas of southeastern Oregon to the more propitious and well-watered region found at the confluence of the Portneuf and Blackfoot streams with the Snake River. When the Bannock moved into the Snake and Lemhi River valleys and the Bridger Basin, they came into close contact with the Shoshone. This association was reinforced by intermarriage between the two groups and is indicated today by the term “Sho-Ban” to refer to the two tribes. Culturally, the two groups shared a common heritage and a similar worldview. They spoke closely related languages: Shoshone is Central Numic, whereas Bannock is Western Numic. With intermarriage between the Shoshone and Bannock, many people were bilingual.

Bannock culture tended to emphasize war more than Shoshone culture. With regard to the merger of the Shoshone and Bannock, it was the Bannock warriors who generally emerged as the most influential leaders of the equestrian Shoshone-Bannock bands.

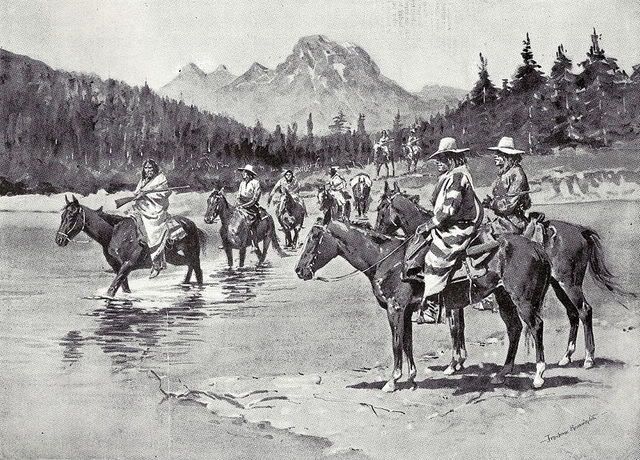

An illustration by Frederick Remington showing a Bannock hunting party during the Bannock Indian War.

A Bannock group is shown above.

Gosiute:

The traditional homeland of the Gosiute was south and west of Great Salt Lake. They lived in the Tooele, Rush, and Skull valleys. A number of scholars feel that the Gosiute are linguistically and culturally Shoshone.

Wild plants were an important part of Gosiute subsistence. They used at least 81 different plants, including 47 plants which were used for their seeds, 12 for berries, 8 for roots, and 12 for greens.

Paiute:

The Paiute tribes are traditionally classified as Northern, Owens Valley, and Southern Paiute. The Northern Paiute traditionally lived in eastern California, western Nevada, and southeast Oregon. For the Northern Paiute tribes, piñon nuts would be gathered in the fall to provide food for winter. The Northern Paiute tribes include Burns Paiute, Upper Sprague River, Salmon Eaters, Root Eaters, Yellow-Bellied Marmot Eaters, Fort McDermitt, Wild Onion Eaters, Mountain Dwellers (also known as the Winnemucca tribe), Rabbit Eaters (Yerrington Paiute Tribe), Pyramid Lake Paiute, Ground Squirrel Eaters (Lovelock Paiute Tribe), Tule Eaters, Trout Eaters (Walker River Paiute), and Pinenut Eaters.

The Owens Valley Paiute are in California and include Big Pine Band, Valley Paiute, Bridgeport Paiute, Lone Pine Paiute, Bishop Paiute, and Utu Utu Gwaitu Paiute.

There 15 to 31 Southern Paiute subgroups, including Chemehuevi, Las Vegas, Moapa, Paranigat, Panaca, Shivwits, St. George, Gunlock, Cedar, Beaver, Panguitch, Uinkaret, Kaibab, Kaiparowits, and San Juan.

As with other tribal groups in the Great Basin, wild plants were an important food and fiber source for these groups. Among the Southern Paiute, for example, seeds were gathered from at least 44 different species of grass. Among the Owens Valley Paiute, seed areas were owned by the band. Women would gather the seeds using a small, paddle-shaped basket which they would use to knock the seeds into a conical container. The seeds would then be winnowed, parched with hot coals, and ground on a flat stone. The seed flour could then be prepared as mush or used for making bread.

Among the Owens Valley Paiute ditch irrigation of wild plants was used to increase the yields. Brush dams were used to divert the water into ditches which ran for miles and which watered multi-acre plots.

Some of the Southern Paiute groups (Shivwit, Chemehuevi, Kaibab, San Juan, and Moapa) were engaged in agriculture.. The Paiute in northern Arizona and southern Utah raised corn, beans, melon, pumpkin, sunflowers, and amaranth. The Southern Paiute people probably learned to raise corn and certain other products from the Pueblo Indians.

The traditional Paiute leader was called niave. This leader led by example and by helping the band to reach consensus. This leader was not a decision-maker, but rather he would offer advice and suggestions at council meetings.

Ute:

The traditional homelands of the Ute peoples included present-day Utah (the name of this state was derived from the name Ute), Colorado, and portions of northern New Mexico. The name “Ute” means “high land.” The Ute tribes included both those who lived in the mountains and those who lived in the desert.

The Ute were never a single unified tribe. There are several bands of the Ute: (1) the Weminuche (Weeminuche) or Ute Mountain Ute whose homeland is the San Juan drainage of the Colorado River, (2) the Tabeguache (also known as Uncompahgre), (3) the Grand River band, (4) the Yampa whose homeland is in northwestern Colorado, (5) the Uintah whose homeland ran from Utah Lake east through the Uinta Basin, (6) the Muache (Moache) whose homeland ranged south along the Sangre de Cristos as far south as Taos, (7) the Capote of the San Luis Valley and the upper Rio Grande, (8) the Sheberetch in the area of present-day Moab, (9) the Sanpits (San Pitch) in the Sanpete Valley in central Utah, (10) the Timanogots near Utah Lake, (11) Pahvant who lived in the deserts surrounding Sevier Lake, and (12) the White River (Parusanuch and Yamparika) in the White and Yampa River systems of Colorado.

The Ute would often trade deer and buffalo hides and meat with the nearby Pueblos for corn and other agricultural products. After the Europeans entered the area, they would also trade hides with the Spanish and other Europeans for horses, knives, and manufactured articles.

Ute bands generally had two chiefs: a chief spokesman and a civil chief. During times of war there might also be a war chief. Each band had a well-defined territory, but their territorial claims were not exclusive. Among the Ute, land was viewed as a gift of creation, to be shared in common. Land was not an object of private possession.

Very interesting overlook of Native American tribes. Thanks

Hello. I live in the n.ga. mens…only 1 hour or so away from Cherokee…yes.i too .i am native American . and Irish.

Hello. My name is pretty flower.

I will tell you the story if and when…we meet. I look forward to conversations…also love the stories of our people…as one people with different lineage.but….with the one mind of creator….we are all one.

Heather Miller

Sunday. Aug. 23 2020

The year of perfect vision.

Thank you! My great grandf. & uncle were lawmen in the old west. Uncle John married the 1/4 Arapaho dau. of Thomas Fitzpatrick, Virginia Thomasine. Both Fitzpatrick & my Gr. uncles were immigrants from county cavan, Ireland. I love that the Indians & Irish seemed to get along so well [most of the time]. Would you please tell me what “The year of perfect vision” means? Lovely! Respect!, Lona