The administration of Indian Affairs in the United States has always been political. The person in charge of Indian Affairs is the Secretary of the Interior who is appointed by the President. Thus, as control of the White House changes, so does the administration of Indian Affairs and the philosophy guiding the relationships between the United States and the many Indian nations.

Political appointments during the 19th century were often made as payments for political debts: they were based on political loyalty rather than on any real administrative talent or understanding of the areas to be administered. This was particularly true with regard to Indian Affairs. By the time of the 1876 Presidential elections, American government was notoriously corrupt and inefficient and within this government, the Office of Indian Affairs was regarded as the most corrupt. In 1876, Rutherford B. Hayes, a Republican, was elected on a platform that promised civil service reform. Upon taking office in 1877, Hayes appointed Carl Schurz, a strong supporter of civil service reform and a Republican politician, as Secretary of the Interior.

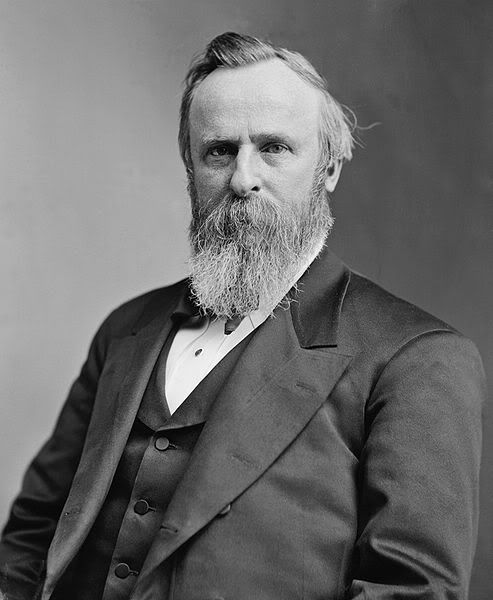

President Rutherford B. Hayes is shown above.

Both Hayes and Schurz strongly supported the assimilation of American Indians into mainstream America, preferring to ignore the racial barriers that prevented this. They stressed educational training to make Indians into loyal, patriotic laborers and servants; the breaking up of Indian reservations into individually owned parcels which then could be more easily transferred to wealthier non-Indians; the dissolution of tribal governments which they felt stood in the way of total assimilation; and the Christianization of Indians through cultural laws which suppressed Native religious traditions and required Christianity.

Upon taking office in 1877, President Rutherford B. Hayes told Congress:

“The faithful performance of our promises is the first condition of a good understanding with the Indians. I can not too urgently recommend to Congress that prompt and liberal provisions be made for the conscientious fulfillment of all engagements entered into by the Government with the Indian tribes.”

Meetings With Indians:

As with most Presidents, Hayes met with a number of different Indian delegations and Indian leaders during his term in office. These meetings were often more ceremonial than substantive. Since Indians were not citizens and could not vote, there was little political reason to consult with them about Indian policies.

One of his first meetings with an Indian delegation came in 1877 when a group of Sioux and Northern Arapaho leaders from the Red Cloud Agency in Nebraska travelled to Washington, D.C. to meet with President Rutherford B. Hayes and the Secretary of the Interior. Representing the Arapaho were Black Coal, Sharp Nose, and Friday. Representing the Sioux were Red Cloud, Big Road, Little Wound, Little Big Man, Iron Crow, Three Bears, American Horse, Young Man Afraid of His Horse, Yellow Bear, Spotted Tail, Swift Bear, Touch the Clouds, Red Bear, White Tail, He Dog, and Little Bad Man.

Black Coal asked that his tribe be allowed to join the Shoshone in Wyoming. He reminded the President of the assistance which his tribe had given the military. He said:

“We want a good place in which to live. We are a small tribe; our village is 170 lodges; we would like to join the Snakes.”

“Snakes” referred to the Shoshone and comes from their sign language symbol for themselves.

Sharp Nose presented a pipe to the President. He reiterated Black Coal’s request to live in Shoshone Country. At the end of the conference, the Americans agreed to send the Arapaho to the Shoshone country in Wyoming. Sharp Nose asked that they be given two black wagons-one for himself and one for Black Coal-in which to transport provisions. The color black symbolizes victory in an encounter with an enemy.

In 1881, a Paiute delegation which included Sarah Winnemucca met with President Rutherford B. Hayes. Hayes entered the room, pontificated about the need for Indians to assimilate into American culture, then left after about five minutes. There was little information exchanged.

Not all of the meetings with Indians took place in the White House. In 1880, President Hayes visited Port Townsend, Washington. Among those who were introduced to the President was Chet-ze-moka (Duke of York), the leader of the Klallam.

Indian Wars:

During the administration of President Rutherford B. Hayes there were a number of Indian wars. In 1877, America’s Christian General, O. O. Howard, was sent to Oregon to force the non-treaty Nez Perce bands who were followers of the pagan Dreamer Religion to resettle on the Christian-run Nez Perce Reservation in Idaho. The result was the Nez Perce war, a conflict that caught the attention of the media and made a war hero out of Chief Joseph, a peace chief who had nothing to do with the battles.

The Nez Perce War was followed by the Bannock War (1878), the Ute War (1879), and the White River War (1879). All of these wars came at a time when there was political pressure to move the Indian Office from the Department of the Interior to the Department of War.

Indian Reservations:

Among the Presidential powers in the nineteenth century was the ability to issue Executive Orders to create new Indian reservations as well as to change the boundaries of reservations. Such Presidential orders did not require authorization or approval from Congress. During his term in office, President Hayes used this power a number of times.

In 1878, President Hayes issued an executive order withdrawing land adjacent to the Navajo Reservation from public domain and making it available for Indian use. The boundary of the reservation was moved 20 miles to the west in order to provide more grazing land for Navajo herds.

A council was held with the Navajo leaders to explain the extension to them. The chiefs complained that they were being crowded by American settlers on all sides. They asked for a similar extension to the east. In 1880, Present Hayes issued an executive order expanding the Navajo reservation in New Mexico 15 miles to the east. There was also an extension of the southern boundary. The executive order forced some American settlers to vacate their farms which heightened resentment against the Navajo.

In 1879, the Salt-River Pima-Maricopa Indian Reservation in Arizona was created by executive order. The community was composed of two tribes: Onk Akimel Au-Authm (Pima) and Xalchidom Pii-pash (Maricopa).

Also in 1879, President Hayes issued an executive order creating the Columbia or Moses Reservation for the non-treaty peoples of the mid-Columbia River area. Sinkiuse chief Moses was considered the leader of these people – Wenatchee, Entiat, Chelan, Methow, Okanagan -even though several of the tribes did not recognize or acknowledge his leadership and authority. Moses collected rent from the American cattle ranchers on the reservation, but he and his band never actually lived on the reservation.

The non-Indian response to the Columbia Reservation was to condemn it as a “barbarous kingdom” for “King Moses” which provided “asylum for renegades to swoop down on the whites to steal horses, rob houses, and murder citizens.”

The Fort Mohave Reservation was established by Presidential executive order in 1880. The reservation was situated along both sides of the Colorado River and included parts of Arizona, California, and Nevada.

In New Mexico, a reservation is established for the Jicarilla Apache by executive order in 1880. While the intent of the order was to provide the Jicarillas with a permanent home, the ink on the order was not even dry before special interest groups began pressuring the Department of the Interior to consolidate the Jicarillas with the Mescalaros and open up the newly created reservation for non-Indian development.

In 1880, it was reported to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs that silver-bearing ore had been discovered in Carbonate Canyon in Arizona and that the only access to this silver would be through the Havasupai village. It was recommended that a reservation be established for the Havasupai which would move their village and prevent trouble. Within a week President Rutherford B. Hayes issued an executive order which reserved lands for the “Suppai” (Havasupai) Indians. However, a few months latter this order was rescinded and different lands was set aside for them. The original order had inadvertently reversed the north and south compass directions. The new reservation was a five mile by twelve mile parallelogram which enclosed the Havasupai farms in Havasu Canyon.

While Presidential executive orders could be used to create and expand Indian reservations, they could also be used to reduce the size of the reservation. In 1880 President Hayes issued an executive order reducing the size of the Fort Berthold Reservation (Mandan, Hidatsa, Arikara) in North Dakota from 7.8 million acres to 1.2 million acres.

The Indian Office:

When Hayes took office in 1877, the Indian Office was notoriously corrupt. Indian Service positions, such as that of Indian Agent, Indian Farmer, and Indian Teacher, were based on political patronage and were used as vehicles for using reservation resources for personal enrichment. It was not uncommon for the Indian Agent, for example, to have an off-reservation store where he sold the annuity goods that were intended for the Indians on the reservation.

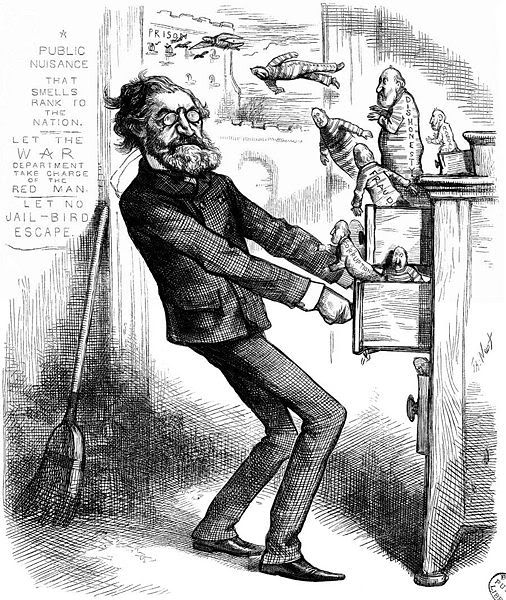

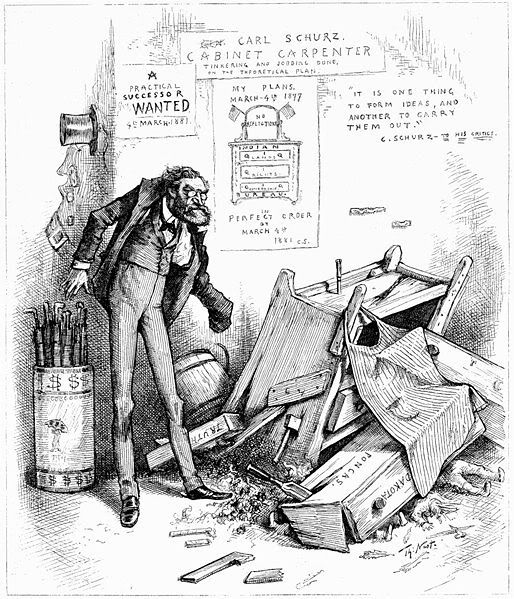

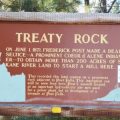

Political cartoons regarding Schurz and the corruption at the Indian Bureau are shown above.

Secretary Schurz attempted to clean up the Indian Office by instituting a wide-scale inspection of the service and by attempting civil service reforms in which positions and promotions were to be based on merit rather than patronage.

Within the Department of the Interior, the Indian Office was under the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, another political appointee. During the Hayes administration there were two Commissioners of Indian Affairs: Ezra Hayt (1877-1880) and Rowland E. Trowbridge (1880-1881). In 1877, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs felt that the best policy for Indians was to gather them on reservations, make them become Christians, compel them to attend school, have Indian police enforce the laws, and assign them to individual plots of land.

In 1878, following the recommendations of the Secretary of the Interior and the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Congress authorized the establishment of Indian police. During the next two years Indian police forces were established on 48 of the 60 reservations in the United States. The new Indian policemen were to be role models for the assimilated Indian: they were to have short hair, wear Euro-American clothing, have only one wife, and accept allotments.

Associated with the Indian police were the Courts of Indian Offenses which were intended to deal with polygamy, the practice of traditional religion, and other activities deemed inappropriate to Anglo ideals.

The Commissioner of Indian Affairs in 1879 issued an order which prohibited the sale of beads and body paint to Indians. These were seen as barriers to their assimilation and ties to their pagan past.

The Ponca:

Newspaper publisher Henry Tibbles promoted the grievances of the Ponca through a series of newspaper articles, a book, and a speaking tour which included Ponca chief Standing Bear. The tour drew packed audiences five to seven nights a week. At a presentation in Worchester, Massachusetts, U.S. Senator George F. Hoar was moved by what he heard. He wrote to President Rutherford B. Hayes expressing his concern at the wrong done to the Ponca by the American government. The President replied that he would give the matter attention.

Rutherford B. Hayes appointed a commission chaired by General George Crook to look into the grievances of the Ponca. Politically, Crook was given the chairmanship in exchange for a promise that the final report would avoid criticizing the government or its individual employees. The final report was to simply determine if the Poncas’ grievances were legitimate and, if so, recommend what should be done to redress those grievances. The Commission report found that the Ponca had been removed without lawful authority and advocated returning all who wanted to return to their old reservation on the Niobrara. The Commission also recommended allotting Ponca land at both reservation sites and paying the Ponca compensation for their mistreatment.

President Hayes presented the report to Congress in 1881. In his memorandum to Congress regarding the Ponca, President Hayes wrote:

“In short, nothing should be left undone to show the Indians that the Government of the United States regards their rights as equally sacred with those of its citizens”

He went on to say:

“The time has come when the policy should be to place the Indians as rapidly as possible on the same footing as the other permanent inhabitants of our country.”

Leave a Reply