One hundred years ago, the primary thrust of American policies with regard to American Indians was assimilation. The goal at this time was to assimilate Indians into the mainstream of American society, to break up the tribes and their reservations, and to continue the process of transferring Indian wealth, in the form of land, from Indians to non-Indians. What follows is a verbal snapshot of that year.

The Supreme Court:

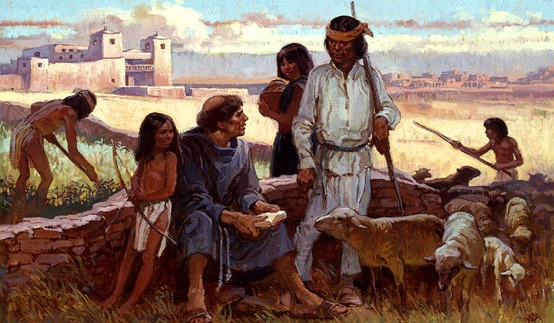

In United States versus Sandoval, the Supreme Court ruled that New Mexico’s Indian Pueblos were under federal jurisdiction. Prior to this ruling, the New Mexico Territorial Government had treated the Pueblos as municipalities. This ruling created concern among non-Indians who claimed ownership of Pueblo lands. According to the court:

“The people of the pueblos, although sedentary rather than nomadic in their inclinations, and disposed to peace and industry, are nevertheless Indians in race, customs, and domestic government. Always … adhering to primitive modes of life, largely influenced by superstition and fetishism [sic], and chiefly governed according to the crude customs inherited from their ancestors, they are essentially a simple, uninformed and inferior people”

The Indian Office:

Since the passage of the Dawes Act in 1887, the United States government had transferred land from Indian to non-Indian ownership. Under the Dawes Act, Indians were given allotments which they were unable to sell. American greed, however, soon led to pressure on the government to allow Indians to sell their land. The Commissioner of Indian Affairs and the Secretary of the Interior instituted a new policy of greater liberalism in which all able-bodied adult Indians were to be given complete control of their property if they have less than one-half Indian blood. Ignoring the reports on the effectiveness of previous competency commissions, the competency commissions were reinstated to determine which Indians were capable of managing their own affairs.

While the Supreme Court in a ruling known as the Winters Doctrine had given Indian tribes superior water rights, the Indian Office sought to minimize this ruling by sending out a memorandum which stated:

“there appears to be no danger of immediate loss of water rights.”

The Indian Office appeared to have little concern for protecting or expanding Indian water rights and seemed more concerned about the impact of Indian water rights on non-Indian water users.

A regional office of the Indian Office complained to the Washington office about the high cost of auctioning off timber leases. The regional office asked for and received permission to take 10 percent of the deposit money from the lease and sale of timber rights. Soon this spread nation-wide and 10 percent of every Individual Indian Money Account deposit was taken for handling the accounts.

The Indian Office sent out a directive to all Indian Agencies which held Indian fairs urging that horse racing be banned because of the gambling associated with it.

The National Indian Memorial:

The National Indian Memorial, authorized by Congress and promoted by Rodman Wanamaker, was dedicated. Many Indian chiefs were brought to New York to participate in the dedication ceremonies. President William Howard Taft presided over the ground-breaking ceremony. Taft told the audience that the Memorial

“tells the story of the march of empire and the progress of Christian civilization to the uttermost limits.”

The Memorial, at the entrance to New York harbor, was to be a 165 foot high statue of an Indian welcoming the European newcomers to America. If the structure had actually been built as planned, it would have been 15 feet higher than the Statue of Liberty.

Wanamaker traveled to all of the reservations in the country bearing an endorsement of the project and a declaration of allegiance to the United States. These were presented to the Indian leaders for their signatures. In return for signing the declaration, each tribe was presented with an American flag. Many of those signing the declaration were not considered citizens by the United States, nor were they allowed to vote.

Indian Head Nickel:

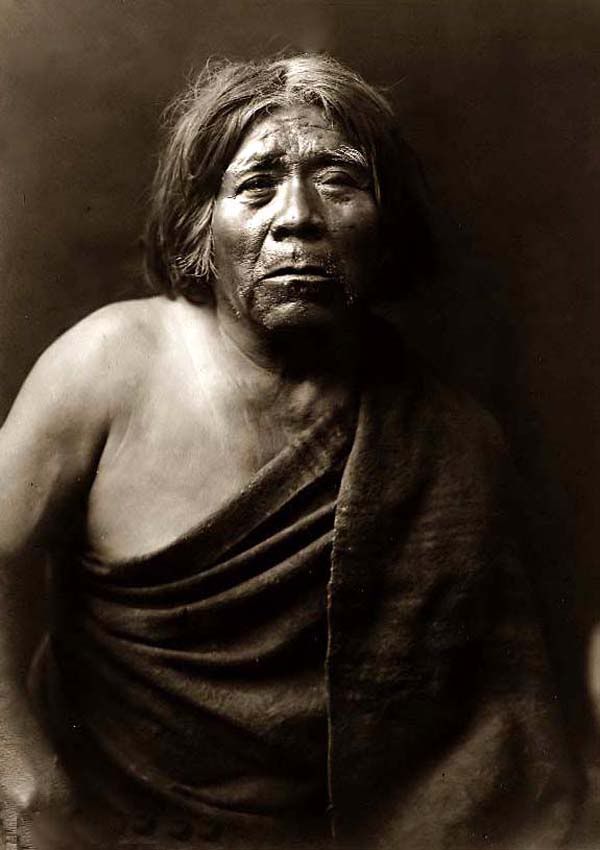

The United States issued the Indian Head nickel which used an Indian head portrait which was a composite of John Big Tree (Onondaga), Iron Tail ((Sioux), and Two Moons (Cheyenne).

Movies, Music, Books, Tourism:

Movie director Thomas Ince traveled to the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota and arranged with the Indian agent to allow 30 Sioux to go to Los Angeles. At this time, Indians were not free to travel off the reservation without the permission of their Indian agent. In Los Angeles, the Indians set up an encampment on the studio’s Santa Monica property. For six months, they appeared in movies and toured the city.

Buffalo Bill Cody produced The Indian Wars, a movie about the massacre of Lakota ghost dancers at Wounded Knee on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota. The movie was filmed on location and used many Lakota actors. Cody chose the reservation as the location for the movie because it was home to significant numbers of professional Indian actors with Wild West show experience. He hoped that this Wild West show experience would translate easily to film.

To portray the American military, Cody arranged for the cooperation of the U.S. Army and General Nelson Miles. Miles insisted that the film show the army story of the battle. Unlike some of the Lakota actors, none of the soldiers had actually taken part in the battle. There was some concern that some of the young Lakota men, in playing the role of 19th century warriors, might strive for realism by using real bullets instead of blanks.

Lakota educator Chauncey Yellow Robe, speaking to the Society of American Indians in 1914, said of the film:

“The whole production of the field was misrepresented and yet approved by the government. This is a disgrace and injustice to the Indian race.”

While Cody had hoped for a blockbuster hit, the film flopped badly. Cody, obsessed with a precision reenactment, did not pay enough attention to story lines and dramatic narrative structures.

A series of Chatacqua camps around the country provided some “educational” musical offerings about Indians. These included works composed by Thurlow Lieurance and Charles Wakefield Cadman whose works were based on Indian music. Performers included Lucy Nicola (Penobscot; she was also called “princess” Watawaso) and Tsianina Blackstone (Cherokee-Creek). In addition to composing music, Cadman gave lectures about Indian music which were illustrated with vocal and piano numbers as well as traditional Indian drums and flute. One of Cadman’s best known songs was “The Land of Sky Blue Water.” The well-meaning non-Indian musicians, in translating Indian music for non-Indian audiences, managed to strip the soul from the music and to replace it with a generic non-Indian soul which reinforced common stereotypes about Indians.

Yankton Sioux writer Zitkala-Sa collaborated on an Indian opera, “Sun Dance.” She provided the composer with some of the detailed rituals of the Sun Dance and played the music of tribal songs on her violin.

The Autobiography of a Winnebago Indian was published in which Sam Blowsnake (also known as Crashing Thunder) told about his life and his conversion to the Native American Church (the “peyote” religion). The book was originally transcribed in a syllabary adapted for use with the Winnebago language and then translated into English by Oliver La Mere.

In South Dakota, Sioux historian Bad Heart Bull (also known as Amos Bad Heart Buffalo and Amos Bad Heart Bull) died at the age of 74. In 1890 he had begun a project of recording tribal history based on what the elders had taught him. The history was done in a pictorial (Winter Count) format and consisted of more than 400 pictures. Among the pictures was a map of the Black Hills which emphasizes its sacred sites.

The Great Northern Railway took a dozen Blackfoot on an extended tour of New York and other cities to promote Glacier National Park. They set up tipis on the roof of the McAlpin Hotel in New York and marched in the Easter Parade. They met with movie star Tom Mix in Chicago. The Blackfeet carried the Glacier Park flag and handed out Glacier Park medallions.

Athletics:

The American Athletic Union stripped Sauk and Fox athlete Jim Thorpe of the medals he won in the 1912 Olympic Games and removed his records from the record books. Thorpe had been paid to play baseball and was thus not considered an amateur athlete. The bylaws for the Olympiad stated that objections to a contestant’s qualifications must be filed within 30 days after the awarding of the prizes. The objection to Thorpe’s qualifications were filed 7 months after the games.

In Maine, Penobscot professional baseball player Louis Sockalexis died of chronic heart disease at the age of 42.

Society of American Indians:

In Colorado, the Society of American Indians (SAI) met in Denver under the auspices of the University of Denver. Membership in the organization was now at 200 active members with most coming from Oklahoma, Montana, South Dakota, Nebraska, and New York. In the meeting, the SAI voted to support a Congressional bill to define Indian status; to support a Congressional bill asking that Indian claims go directly to the federal court of claims; and a reorganization of Indian schools.

Chauncey Yellow Robe (Lakota) spoke out against three decades of Wild West Shows. He called these shows degrading, demoralizing, and degenerating. He said:

“All these Wild West Shows are exhibiting the Indian worse than he ever was and deprive him of his high manhood and individuality.”

The SAI began to publish the Quarterly Journal. Dr. Carlos Montezuma (Yavapai-Apache) was designated to serve as contributing editor.

The Society of American Indians called for the opening of the Court of Claims to Indian tribes. The Society called for Congress to enact such legislation that would give the tribes a five-year opportunity to submit their claims against the Unites States. At this time, Indian tribes could only sue the United States with Congressional approval. Acting with their usual speed regarding Indian affairs, Congress would finally enact this type of legislation 35 years later.

Leave a Reply