Very often in history classes and in the popular media Indians are segregated into the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries with particular attention on the conflicts with Plains Indians following the Civil War. There is sometimes the implication that there were no Indians in the twentieth century, that they had somehow gone extinct or simply assimilated, like other immigrants, into mainstream American culture. Yet twentieth century American history is filled with incidents of violent conflicts (wars?) and political policies regarding Indians. Discussed below are some of the events and issues of just one year: 1964, a mere two generations in the past.

Federal Policy:

Indian leaders come to Washington, D.C. to lobby for a change in the War on Poverty legislation that would allow grants to be made directly to Indian tribes. When the legislation creating the Office of Economic Opportunity finally passes it includes their proposal. This marks a milestone in federal and tribal relations, in that, for the first time, Indian people had conceived of a provision to be inserted in national legislation and then lobbied it through Congress into law.

The War on Poverty programs, unlike many federal programs, had a positive impact on Indian reservations. Not only did these programs realistically address economic, educational, and health issues, they also provided a training ground for future Indian leaders. Programs dealing with mental health and alcoholism gave Indian people the expertise to deal with these issues.

Fishing and Gathering Rights:

Treaties between the United States and Indians nations often stated very clearly that the Indian nations had retained their traditional rights to fish, hunt, and gather in all usual and accustomed places. State governments, however, have not felt any obligation to conform to these treaties and have openly violated Indian rights.

Northwest Indians initiate a series of “fish-ins” in Western Washington. State response is brutal: Indian men, women, and children are arrested using tear gas, blackjacks, and violence. After state officers in riot gear in a high speed aluminum boat capsize his cedar canoe, Nisqually tribal member Billy Frank, Jr. comments: “These guys had a budget. This was war.”

In Washington, the Makah erect a smokehouse on Olympic National Park land near the mouth of the Ozette River. The Park Service acknowledges their treaty rights and drafts regulations that allow seasonal structures.

In Wisconsin, game wardens arrest a number of Bad River Chippewa for illegally harvesting wild rice in the Kakagon Slough. The tribe’s regulations for harvesting wild rice differ from those of the state. The tribal council insists that the state has no jurisdiction over Indian wild rice.

Recognition:

In North Carolina, the Haliwa-Saponi win a lawsuit which forces the state to change the birth certificates of tribal members to identify them as Indians.

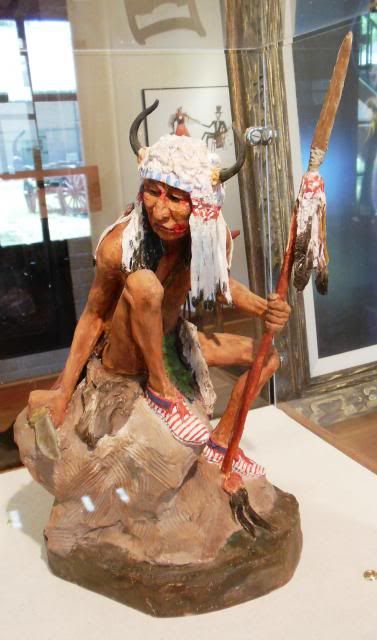

American Indian Art:

In Washington, D.C., an exhibition of student work from the Institute of Indian Arts in Santa Fe, New Mexico is exhibited in the offices of the Department of the Interior.

Cochiti Pueblo artist Helen Cordera makes her first Storyteller figure – a grandfather seated with five children hanging from him. The figurative pottery is inspired by memories of her grandfather telling stories to the children of Cochiti. This innovation will inspire many other potters and will become one of the most popular Native art forms in the southwest.

In New Mexico, Tewa artist Helen Hardin has her first “formal” one-woman show at Enchanted Mesa. She recalls of the event: “I was treated like a cute little Indian girl—so sweet, so beautiful.”

Mission Indian artist Fritz Scholder vows that he will never paint another Indian and resolves to invent a new style of Indian painting summarized as: “I have painted the Indian real, not red.” Scholder declares: “The non-Indian had painted the subject as a noble savage and the Indian painter had been caught in a tourist-pleasing cliché.”

Land Issues:

A group of about 40 Indians travel to Alcatraz Island in California by boat. Allen Cottier, a Sioux descendent of Crazy Horse, reads a statement offering 47 cents per acre for the purchase of the island.

In Arizona, the Havasupai ask the National Park Service to relinquish administrative control over the Grand Canyon National Park campground located adjacent to the Havasupai Reservation.

In Arizona, the Chemehuevi and Mojave of the Colorado Indian Reservation win their fight against having tribes from outside their reservation establish colonies on the reservation. Congress passes legislation to change the policy.

In Washington, D.C., once again a bill is introduced in Congress which would provide the Yaqui with land in Arizona. To make the bill more palatable for some termination-minded Senators, the bill states: “Nothing in this Act shall make such Yaqui Indians eligible for any services performed by the United States for Indians because of their status as Indians, and none of the statutes of the United States which affect Indians because of their status as Indians shall be applicable to the Yaqui Indians.”

The bill manages to pass and on Halloween, the Yaqui hold a ceremony commemorating the transfer of the 200 acres of land to the Pascua Yaqui Association. Anselmo Valencia makes speeches in both Yaqui and Spanish.

In Wisconsin, Aztalan State Park, the site of an ancient Mississippian settlement, becomes a National Landmark.

In Maine, non-Indians attempt to develop Passamaquoddy land. The Passamaquoddy attempt to enlist the aid of the Governor, but are told that this is a local affair. The Passamaquoddy stage a protest and several are arrested. The attorney hired by the Passamaquoddy is given a bunch of old papers from an old Indian who had died. In these papers is the original handwritten treaty between the Passamaquoddy and the Commonwealth of Massachusetts which was signed in 1794. The treaty is then used as evidence to get the charges against the protesters dismissed. (Note: Maine was a part of Massachusetts when the treaty was signed.)

In Utah, a handful of terminated mixed-blood Ute hire attorney Parker Nielson to investigate possible securities fraud in conjunction with the Ute Distribution Corporation.

The Peabody Coal Company signs a lease with the Navajo allowing for the strip mining of 40,000 acres on the Navajo Reservation.

In Wyoming, the Northern Arapaho distribute their land claim payment to each enrolled member in the form of 12 monthly payments of $124.

Urban Indians:

In California, Friendship House opens as a drop-in facility for treating drug and alcohol abuse in San Francisco’s Indian population.

In Chicago, Illinois, St. Augustine’s Center for American Indians begins an annual buffalo dinner as a fund-raiser. More than 100 people pay $50 per plate for the event.

Media, Education, Sports:

The newsletter Powwow Trails begins publication. It provides a monthly calendar of Indian and hobbyist events as well as articles about powwows, music, dance, and Indian material culture.

The movie Cheyenne Autumn attempts to portray Indians in a positive light. While the title suggests that the movie comes from a book by Mari Sandoz, English professor Raymond William Stedman, in his book Shadows of the Indian: Stereotypes in American Culture, feels that “Virtually any source, however, the Omaha telephone book included, would have served as well for this unfortunate and interminable strip of celluloid.”

The American Indian Historical Society is founded by Rupert Costo (Cahuila). The new organization hopes to correct the common stereotypes about American Indians and provide a more accurate presentation of Indians in American history.

In Mississippi, a high school for the Choctaw is opened.

Billy Mills (Oglala Sioux) wins the 10,000 meter run in the Olympic Games. He is the first American to win this event.

Leave a Reply