In 1851, the United States government met in treaty council with 8,000 to 12,000 Indians from several Plains tribes at Fort Laramie in present-day Wyoming. One of the tribes attending this council was the Cheyenne. While many Americans assumed that the Cheyenne had always been a Plains tribe, in fact, when Europeans first encountered them in the early 1600s they were living in the woodlands at the mouth of the Wisconsin River in what is now Minnesota. Like the other tribes in this area at this time, the Cheyenne lived in permanent or semi-permanent villages making their living by farming.

Prior to living in Minnesota, Cheyenne oral tradition says that the people lived far to the northeast in what is now Canada. They were not farmers at this time, but lived by fishing, hunting and gathering wild plant foods. According to tradition, they were living by a large body of water. There was, however, a time of great sickness and the people left their homeland and moved south. The Cheyenne call this the “ancient time” when the people were happy but were decimated by a terrible disease leaving the people as orphans.

They next settled in the marshy areas between Ontario and Minnesota and it was here that they learned farming from the other tribes in the area. The Cheyenne call this the “time of the dogs” when dogs were used as beasts of burden.

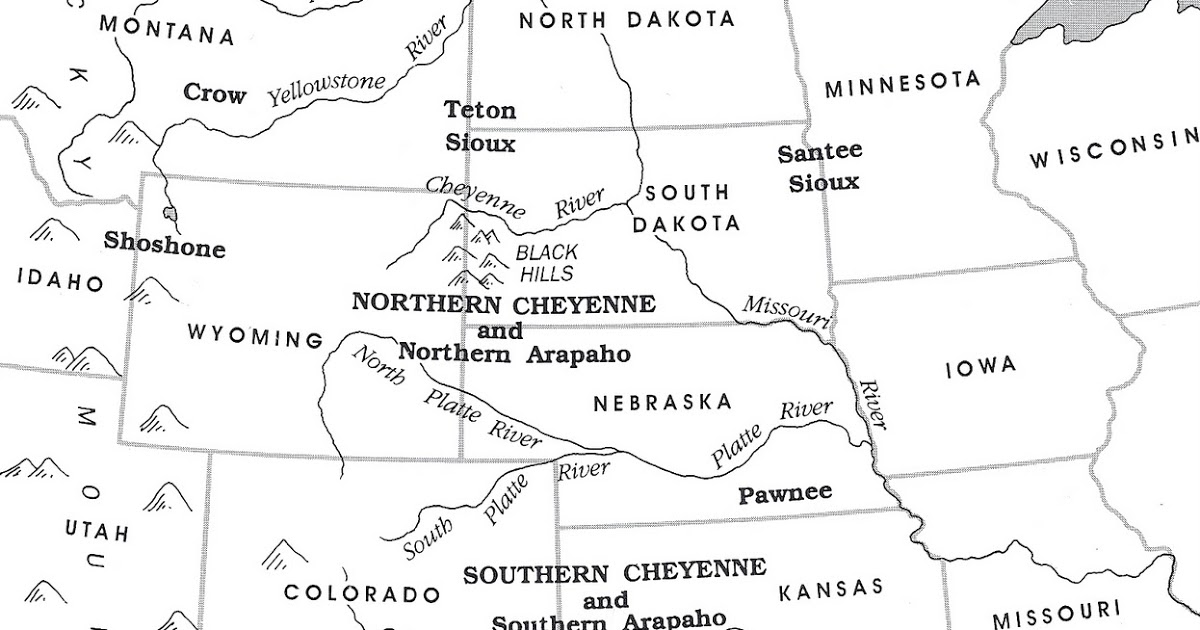

About 1635, the Cheyenne began their slow migration westward toward the Great Plains. Their migration may have been motivated or initiated in part by the westward expansion of tribes to the east including the Sioux, Iroquois and the Anishinaabe. The many villages that made up the Cheyenne did not move all at one time, but rather they moved piecemeal. Archaeological data suggests that it may have taken two centuries for all of the different groups to migrate west of the Mississippi River and into the Great Plains. By 1700 many of the bands were living in the Sheyenne River Valley in eastern North Dakota. Here they adopted the life-style of the farming tribes in that region which included living in villages made up of semi-subterranean earthlodges. They continued to farm corn, beans, and squash.

In the mid-1700s, the Plains Cree, Plains Ojibwa, and the Assiniboine pushed the Cheyenne farther west. The Cheyenne re-established themselves in the Black Hills area where they acquired the horse and became nomadic buffalo hunters. In the Black Hills, the Cheyenne encountered the Arapaho who had probably moved out of the Minnesota area ahead of them. While the Arapaho had moved into the Black Hills first, they did not view the Cheyenne as intruders, but welcomed them as friends. The two tribes intermarried and became confederated.

Pressure from the Teton Sioux toward the end of the eighteenth century pushed the Cheyenne even farther west. Once again, this migration was carried out piecemeal. By 1800, the Cheyenne still had some villages which were planting corn along the Missouri River. After 1825, the Cheyenne began to divide into a Northern tribe and a Southern tribe. The Southern Cheyenne continued their close association with the Arapaho while the Northern Cheyenne developed a close association with the Sioux.

At Fort Laramie in 1851, the Americans failed to distinguish between the Northern Cheyenne and the Southern Cheyenne. The Americans in their infinite wisdom assumed that there was only one Cheyenne tribe and “awarded” them a reservation in what would become Oklahoma. The Southern Arapaho were also assigned to this reservation.

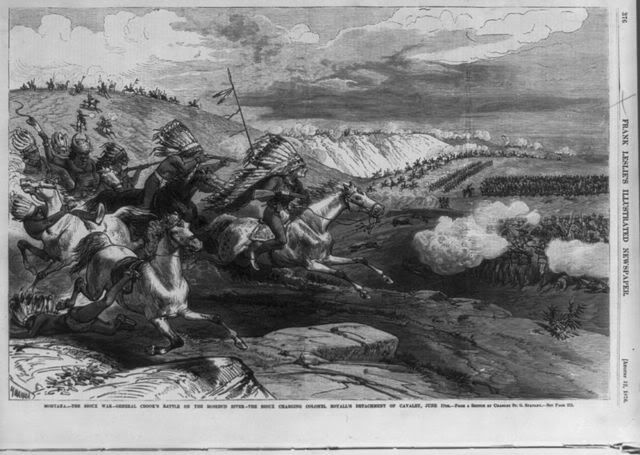

The Northern Cheyenne had no intention of moving to a reservation on the Southern Plains so they stayed in the north where they affiliated themselves with the Sioux. However, following the Battle of the Little Bighorn where the Sioux and Cheyenne defeated a surprise attack led by Lt. Colonel George Custer, the Northern Cheyenne were scattered as the Americans attempted to force them to move to the reservation. Finally, in 1882, the government moved the Northern Cheyenne under the leaders Two Moon and White Bull to a small reserve on Rosebud Creek and the Tongue River in Montana. This marked the beginning of the formation of the Northern Cheyenne Reservation.

Please keep all body’s of water clean and recycle all of what mankind can❣️